Products: ABAQUS/Standard ABAQUS/CAE

This section highlights the difficulties that are most commonly encountered when modeling contact interactions with ABAQUS/Standard. Recommendations on how to circumvent these problems are presented.

It is important to understand how ABAQUS/Standard interprets and resolves contact conditions at the start of a step or analysis. If necessary, you can check initial contact conditions in the message file (see “The ABAQUS/Standard message file” in “Output,” Section 4.1.1). Unintentional contact openings or overclosures can lead to poor interpretations of surface geometry, unintentional motion in a model, and failure of an analysis to converge.

When modeling the contact between two faceted surfaces, it is often possible for small gaps or penetrations to occur at individual nodes. This problem is particularly common when the two surfaces have dissimilar meshes. By default, ABAQUS/Standard interprets initial penetrations as interference fits and tries to resolve them accordingly (see “Modeling contact interference fits in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.4). You can improve the accuracy of a contact simulation by having ABAQUS/Standard adjust the position of the slave surface to ensure that all slave nodes that should initially be in contact with the master surface start out in contact without any penetration (see “Adjusting the surfaces in a contact pair” in “Adjusting initial surface positions and specifying initial clearances in ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.5). When an intended initial clearance or overclosure is small compared to typical dimensions of the bodies in contact and small-sliding contact is used, you can specify the clearance or overclosure precisely (see “Defining a precise initial clearance or overclosure for small-sliding contact” in “Adjusting initial surface positions and specifying initial clearances in ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.5).

The small-sliding contact tracking approach is more sensitive than the finite-sliding tracking approach to initial local gaps at the contact interface. In small-sliding contact each slave node interacts with a contact plane defined from the finite element approximation of the master surface, as discussed in “Contact formulation for ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.2. ABAQUS/Standard can define these planes only when each slave node can be projected onto the master surface. Having these slave nodes start the simulation contacting the master surface allows ABAQUS/Standard to form the most accurate contact planes for the slave nodes.

Rigid body motion is generally not a problem in dynamic analysis. In static problems rigid body motion occurs when a body is not sufficiently restrained. “Numerical singularity” warning messages and very large displacements indicate unconstrained motion in a static analysis. Therefore, if contact pairs are used to constrain rigid body motion in static problems, ensure that the appropriate surface pairs are initially in contact (see “Adjusting initial surface positions and specifying initial clearances in ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.5). If necessary, define the model geometry to give a small initial overclosure to the contact pair, or use boundary conditions to move the structures into contact in the first step. The boundary conditions, which are unnecessary in subsequent steps, can be removed after the body is adequately constrained through contact with other components. Similarly, if a rigid body is meant to translate only, constrain its rotational degrees of freedom.

Frictional sticking can constrain rigid body motion. However, contact pressure must develop before friction can be generated. Therefore, friction is not effective in constraining rigid body motion when surfaces first come into contact. You must temporarily eliminate rigid body motion by defining a boundary condition or by grounding the body with soft springs or dashpots.

If you are unable to prevent rigid body motion through modeling techniques, ABAQUS/Standard offers some tools to automatically stabilize rigid bodies in contact simulations. These tools are discussed in “Automatic stabilization of rigid body motions in contact problems” in “Adjusting contact controls in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.12.

ABAQUS/Standard interprets initial overclosures as interference fits, which it tries to resolve in the first increment of a step. If the initial overclosures are an unintended result of mesh discretization, you should use one of the methods discussed above to remove the overclosures. In some cases the interference fit may be intended but too large for ABAQUS/Standard to resolve in a single increment. In this situation you should redefine the interference fit to allow resolution of the overclosures over multiple increments. See “Modeling contact interference fits in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.4, for more information.

Over the course of an analysis, you may notice undesirable behavior between contact pairs (excessive penetration, unexpected openings, inaccurate application of forces, etc.). This behavior often results in nonconvergence and termination of an analysis. These problems can arise from a number of causes related to mesh, element selection, and surface geometry.

When defining three-dimensional surfaces for use in finite-sliding applications, avoid defining two surface nodes with the same coordinates. Such a definition can give rise to a seam, or crack, in the surface as shown in Figure 29.2.11–1.

If viewed with the default plotting options in ABAQUS/CAE, this surface will appear to be a valid, continuous surface; however, if this surface is used as the master surface for finite-sliding, node-to-surface contact, a slave node sliding along the surface may fall through this crack and get “stuck” behind the master surface. Similar problems can occur for finite-sliding, surface-to-surface contact. Typically, convergence problems will result that may cause ABAQUS/Standard to terminate the analysis.Use the edge display options in the Visualization module of ABAQUS/CAE to identify any unwanted cracks in the surfaces used in the model. The cracks will appear as extra perimeter lines in the interior of the surface. Duplicate nodes can be avoided easily by equivalencing nodes when creating the model in a preprocessor.

When modeling finite-sliding contact, ensure that the master surface definition extends far enough to account for all expected motions of the contacting parts. Contact along the perimeter of master surfaces should be avoided. ABAQUS/Standard assumes that the mating slave surface nodes can fall off the free edge of the master surface, which can cause problems if a slave node wraps around and approaches its mating master surface from behind. Figure 29.2.11–2 illustrates appropriate and inappropriate master surface definitions.

A slave node that falls off a master surface in one iteration may find itself contacting the surface in the very next iteration; this phenomenon is known as chattering. If chattering continues, ABAQUS/Standard may not be able to find a solution. This problem is less likely with the surface-to-surface formulation approach, because each contact constraint is based on a region of the slave surface rather than individual slave nodes. Request detailed contact printout to the message (.msg) file to monitor the history of a slave node that might slide off the master surface (see “The ABAQUS/Standard message file” in “Output,” Section 4.1.1). The message file output will show the cyclic opening and closing of contact at a slave node, which will indicate where the master surface needs to be modified.For node-to-surface contact you can extend the master surface beyond the perimeter of the physical body that it approximates to avoid chattering problems. Chattering can also occur with some contact elements, such as slide line and rigid surface contact elements. Slide line contact elements can also be extended. See “Extending master surfaces and slide lines,” Section 29.2.8, for details.

Falling off the edge of a master surface in small-sliding contact problems is not an issue since slave nodes do not slide on the actual surface of the model. Instead, each slave node interacts with a flat, infinite contact plane. This plane is associated with the set of master surface nodes that are closest to the slave node in the undeformed configuration. For details about small-sliding contact, see “Contact formulation for ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.2.

Several problems are caused by surfaces created on very coarse meshes.

When a coarsely meshed surface is used as a slave surface for node-to-surface contact, the master surface nodes can grossly penetrate the slave surface without resistance (see Figure 29.2.11–3). This situation is common when nonmatching meshes come into contact. Refining the slave surface tends to alleviate this problem.

Surface-to-surface contact will generally resist penetrations of master nodes into a coarse slave surface; however, this formulation can add significant computational expense if the slave mesh is significantly coarser than the master mesh (see “Defining contact pairs in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.1, for further discussion).

Coarsely meshed, curved master surfaces in small-sliding simulations can lead to unacceptable solution accuracy due to the approximate nature of the “master planes.” Using a more refined mesh to define the master surface will improve the overall accuracy of the solution in small-sliding problems. However, unless perfectly matching meshes are used, local oscillations in the contact stress may still be observed, even in refined models.

Inaccurate local results may occur if second-order heat transfer elements are used to model a thermal interface and the meshes do not match across the surfaces. The worst results will be obtained when the midside node of an element on one surface is closest to the corner node of an element on the other surface. If a nonmatching mesh must be used in the model, use first-order elements or use a more refined mesh.

Second-order elements not only provide higher accuracy but also capture stress concentrations more effectively and are better for modeling geometric features than first-order elements. However, some of the second-order elements may not be suited for contact simulations with the default “hard” contact relationship or for analyses requiring large element distortions.

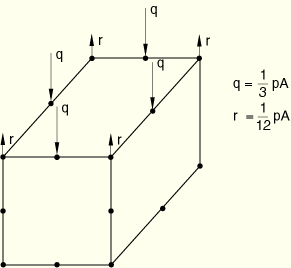

Some second-order elements can be problematic in contact simulations with the strictly enforced “hard” contact relationship because of the distribution of equivalent nodal forces when a pressure acts on the face of the element. As shown in Figure 29.2.11–4, a constant pressure applied to the face of a second-order element, which does not have a midface node, produces forces at the corner nodes acting in the opposite sense of the pressure.

Figure 29.2.11–4 Equivalent nodal loads produced by a constant pressure on the second-order element face in “hard” contact simulations.

The element families C3D20(RH), C3D15(H), S8R5, and M3D8 are converted to the families C3D27(RH), C3D15V(H), S9R5, and M3D9, respectively. Since ABAQUS/Standard does not convert second-order coupled temperature-displacement and coupled pore pressure–displacement elements, you should specify a penalty or augmented Lagrange constraint enforcement method to approximate hard pressure-overclosure behavior (see “Constraint enforcement methods for ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.3). ABAQUS/Standard will interpolate nodal quantities, such as temperature and field variables, at the automatically generated midface nodes when values are prescribed at any of the user-defined nodes.

The modified second-order tetrahedral elements (C3D10M) in ABAQUS/Standard are designed to be used in complex “hard” contact simulations. Regular second-order tetrahedral elements (C3D10) have zero contact force at their corner nodes, leading to poor predictions of the contact pressures. They should, therefore, not be used in “hard” contact problems. The modified second-order tetrahedral elements can calculate the contact pressures accurately.

Second-order elements can be used in contact simulations with a penalty or augmented Lagrange constraint enforcement method (see “Constraint enforcement methods for ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.3) to yield better stress distributions at the contact interface. The regular tetrahedral elements may not perform well in analyses involving impact or nearly incompressible material response, such as in problems with a large amount of plastic deformation. The modified second-order tetrahedral elements should be used in these circumstances.

ABAQUS/Standard offers a number of methods to adjust the solver iteration scheme, sometimes resulting in a more efficient analysis with a minimal effect on accuracy.

ABAQUS/Standard distinguishes between regular, equilibrium iterations (in which the solution varies smoothly) and severe discontinuity iterations (SDIs) in which abrupt changes in stiffness occur. The most common of such severe discontinuities involve open-close changes in contact and stick-slip changes in friction. By default, ABAQUS/Standard will continue to iterate until no severe discontinuities occur and the equilibrium (flux) tolerances are satisfied. However, forcing a new iteration whenever a severe discontinuity occurs can sometimes lead to convergence problems.

There are two cases where the default approach may lead to convergence trouble or excessively small time increments. The first case occurs when contact conditions are (almost) undetermined. For example, if a flat punch makes contact with a thin plate that is supported at its edges, the contact condition in the center of the punch is not well determined. Typically, if a point is in contact, the contact stress is small; and if a point is not in contact, the opening distance is small as well. Such conditions can lead to excessive contact “chattering,” where ABAQUS keeps changing the contact conditions without changing the solution significantly. The second case occurs for very large contact problems (problems with many contact points). In such problems it often takes many iterations to settle the (initial) contact conditions. By default, such a large number of iterations is not allowed, and ABAQUS cuts back the increment size to excessively small values to limit the number of contact changes.

In both of these cases you can correct the problem by changing the contact definition or by increasing the maximum number of severe discontinuity iterations (see “Severe discontinuity iterations” in “Convergence criteria for nonlinear problems,” Section 7.2.3). However, you will have to examine the problem carefully to determine what you need to do, since you may otherwise make the problem worse. For example, if you increase the maximum number of iterations in a situation when chattering occurs, the analysis may still not converge but may end up doing more iterations. Hence, it is desirable for the iteration control algorithm to automatically recognize whether the changes in contact are significant and whether additional iterations with the current time increment size are likely to be fruitful. A non-default version of the iteration control algorithm with these characteristics is available in ABAQUS/Standard. This algorithm is based on converting severe discontinuity iterations into representative force residuals. ABAQUS/Standard will stop iterating when the residual tolerances are satisfied, even if trivial changes in contact occur. This strategy will often deal effectively with the chattering problem and the resolution of large contact simulations discussed previously. The SDI conversion capability is discussed in more detail in “Severe discontinuities in ABAQUS/Standard” in “Procedures: overview,” Section 6.1.1.

For most types of contact, if during an iteration the penetration calculated for any contact pair exceeds a specific distance (![]() ), ABAQUS/Standard abandons the increment and tries again with a smaller increment size. There is no critical penetration distance for finite-sliding, surface-to-surface contact and for small-sliding contact in geometrically linear analyses.

), ABAQUS/Standard abandons the increment and tries again with a smaller increment size. There is no critical penetration distance for finite-sliding, surface-to-surface contact and for small-sliding contact in geometrically linear analyses.

The default value of ![]() is the radius of a sphere that circumscribes a characteristic surface element face. When calculating the default value, ABAQUS/Standard uses only the slave surface of the contact pair. The value of

is the radius of a sphere that circumscribes a characteristic surface element face. When calculating the default value, ABAQUS/Standard uses only the slave surface of the contact pair. The value of ![]() for each contact pair in the model is printed in the data (.dat) file. While the default value of

for each contact pair in the model is printed in the data (.dat) file. While the default value of ![]() should prove to be sufficient for the majority of contact simulations, in some cases it may be necessary to change the default value for a given contact pair. These cases include:

should prove to be sufficient for the majority of contact simulations, in some cases it may be necessary to change the default value for a given contact pair. These cases include:

Models in which the master surface is highly curved. The default value of ![]() may sometimes lead to situations as shown in Figure 29.2.11–5. During the iterative solution process a slave node initially at point a may move to point b, penetrating the master surface with overclosure h less than

may sometimes lead to situations as shown in Figure 29.2.11–5. During the iterative solution process a slave node initially at point a may move to point b, penetrating the master surface with overclosure h less than ![]() . ABAQUS/Standard may attempt to move the slave node to point c on the master surface. To avoid this situation, specify a smaller value for

. ABAQUS/Standard may attempt to move the slave node to point c on the master surface. To avoid this situation, specify a smaller value for ![]() to force ABAQUS/Standard to abandon the increment and to try a smaller increment size.

to force ABAQUS/Standard to abandon the increment and to try a smaller increment size.

Models in which ABAQUS/Standard cannot calculate a reasonable ![]() because a node-based surface is used. If there are other contact pairs in the model with surfaces, ABAQUS/Standard uses the average dimension of all of the slave surface element faces. If there are no other contact pairs, ABAQUS/Standard uses a characteristic element dimension of the entire model.

because a node-based surface is used. If there are other contact pairs in the model with surfaces, ABAQUS/Standard uses the average dimension of all of the slave surface element faces. If there are no other contact pairs, ABAQUS/Standard uses a characteristic element dimension of the entire model.

Models in which the contact face dimensions in a slave surface vary greatly.

Models in which the slave surface mesh is very refined compared with the typical surface dimensions so that overclosures much larger than the default ![]() can be resolved easily.

can be resolved easily.

Models in which contact pairs with softened contact allow significant penetration (see “Contact pressure-overclosure relationships,” Section 30.1.2).

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT PAIR, HCRIT= |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | You cannot adjust the default value of |

Although an analysis involving contact runs to completion, the results may seem unrealistic. This is sometimes due to modeling errors and sometimes due to the specialized output format of certain contact formulations.

Nonuniform contact pressure distributions are likely to occur when very different mesh densities are used on the two deformable surfaces making up a contact pair. The nonuniformity can be particularly pronounced when “hard” contact is modeled and both surfaces are modeled with second-order elements, including modified, second-order tetrahedral elements. In such cases oscillations and “spikes” in the contact pressure may occur. Smoother contact pressures may be obtained for surfaces modeled with second-order elements by using penalty-type contact constraint enforcement (see “Constraint enforcement methods for ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.3).

For second-order axisymmetric elements the contact area is zero at a node lying on the symmetry axis ![]() . To avoid numerical singularity problems caused by a zero contact area, ABAQUS/Standard calculates the contact area as if the node were a small distance from the symmetry axis. This may result in inaccurate local contact stresses calculated for nodes located on the symmetry axis.

. To avoid numerical singularity problems caused by a zero contact area, ABAQUS/Standard calculates the contact area as if the node were a small distance from the symmetry axis. This may result in inaccurate local contact stresses calculated for nodes located on the symmetry axis.

Contact of a surface with itself (self-contact) is provided for cases in which the original geometry is very different from the (deformed) geometry at which contact takes place. It would then be difficult for you to predict which parts of the surface will come into contact with each other. Where possible, it is always computationally more economical to declare parts of the surface as master and parts as slave. The same unpredictability makes it impossible to determine a priori which side will be the master and which side the slave. Therefore, ABAQUS/Standard uses a symmetric contact model: every single node of the surface can be a slave node and can simultaneously belong to master segments with respect to all other nodes.

Because each surface is acting as both a slave and a master, the results of symmetric contact analyses can be confusing and inconsistent. These difficulties are discussed more fully in “Using symmetric master-slave contact pairs to improve contact modeling” in “Defining contact pairs in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.1.

The term overconstraint refers to a situation in which multiple kinematic constraints outnumber the degrees of freedom on which they act. Overconstraints often lead to inaccurate solutions or failure to obtain a converged solution. Contact conditions strictly enforced with the direct constraint enforcement method (using Lagrange multipliers) are sometimes involved in overconstraints. See “Overconstraint checks,” Section 28.6.1, for a detailed discussion and examples of overconstraints and how ABAQUS/Standard will treat overconstraints based on the following classifications:

Overconstraints detected in the model preprocessor

Overconstraints detected and resolved during analysis

Overconstraints detected in the equation solver

Contact conditions with a softened behavior or enforced with the penalty or augmented Lagrange method will not combine with other constraints to cause “strict overconstraints”; however, “softened overconstraints” can:

cause zero pivots or ill-conditioning in the equation solver if the stiffness contributions associated with contact are many orders of magnitude higher than the stiffness contributions from typical elements;

prevent a tight penetration tolerance from being achieved with the augmented Lagrange method; and

cause oscillations in contact stress solutions, particularly if the contact stiffness is high.

If nodes in a contact pair are overconstrained but the equation solver does find a solution, the contact forces become indeterminate and may become excessively high, particularly in tied contact pairs. Check the time average force (or moment, or flux) reported in the message file, or use ABAQUS/CAE to view the diagnostic information interactively (for more information, see Chapter 23, “Viewing diagnostic output,” of the ABAQUS/CAE User's Manual). If it is many orders of magnitude larger than the residual forces (or moments, or fluxes), an overconstraint may have occurred, and there is no guarantee that ABAQUS/Standard has found the correct solution. Another sign that the model is overconstrained is that the analysis begins to converge in a single iteration in every increment when the nonlinearities should require at least several iterations. Overconstraints should be avoided only by changing the contact definition or other constraint type involved.

The different contact formulations available in ABAQUS/Standard (see “Defining contact pairs in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.1) allow for a great deal of flexibility when modeling contact simulations. However, two nearly identical simulations that differ only in the contact formulation being used will sometimes generate varying results. This is primarily because of the different ways that contact formulations interpret contact conditions. Certain formulations are better suited to particular situations.

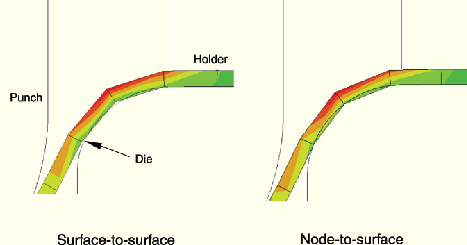

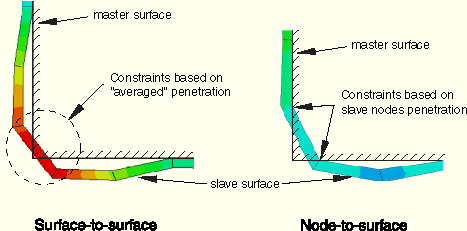

The most observable difference between node-to-surface and surface-to-surface discretization is the amount of penetration that occurs between surfaces. This is because node-to-surface discretization computes penetrations only at slave nodes, while surface-to-surface discretization computes penetrations in an average sense over a finite region. For example, when a slave surface slides across a convex portion of a master surface, the slave surface will tend to ride a bit higher with surface-to-surface discretization than with node-to-surface discretization, as shown in Figure 29.2.11–6 (the opposite is true at a concave portion of a master surface). Figure 29.2.11–7 shows another case in which the two contact discretizations behave fundamentally differently due to the different approaches to computing penetrations. Both discretizations converge to the same behavior as the mesh is refined.

Figure 29.2.11–6 Comparison of contact discretizations in an example with convex curvature in the master surface (forming application).

Figure 29.2.11–7 Comparison of contact discretizations in an example with a relatively flexible slave surface wrapping around a corner of a master surface.

The differences in computed penetrations can sometimes fundamentally affect the results of an analysis. Be aware of this possibility when converting models from one contact formulation to another. Various aspects of preexisting models, such as the friction coefficient or the pressure-overclosure relationship, may have been inadvertently “tuned” to the behavior that occurs with a particular contact formulation.

In certain simulations where contact is intended to occur at a single point between two surfaces, you may encounter difficulties with surface-to-surface contact discretization. Figure 29.2.11–8 shows an example in which a circular rigid body is pushed into a deformable body.

In the initial configuration shown, the two bodies touch at a single point, which corresponds to a slave node location. The following scenarios are likely for respective analyses of this model with node-to-surface and surface-to-surface discretization:With node-to-surface discretization, the first iteration is performed with one active contact constraint. A converged solution is obtained with a reasonable number of iterations and increments.

With surface-to-surface discretization, penetrations are computed in an average sense over finite regions of the surface, so a positive gap distance is computed for all potential contact constraints even though the surfaces touch at one of the slave nodes. Therefore the first iteration is performed without any active contact constraints. The lack of any active contact constraints causes an unconstrained rigid body mode, which prevents ABAQUS/Standard from obtaining a converged solution.

You should not conclude that surface-to-surface contact discretization cannot be used in such cases. Instead, one of the following simple modeling techniques can be added to obtain an accurate solution:

Activate one of the automatic contact stabilization methods (see “Automatic stabilization of rigid body motions in contact problems” in “Adjusting contact controls in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.12).

Specify that ABAQUS/Standard should adjust initial surface positions within an adjustment zone (as discussed in “Adjusting initial surface positions and specifying initial clearances in ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 29.2.5) such that at least one contact constraint is initially active. Note that this approach can only be used to properly establish new contacts in the first analysis step.

When modeling large interference fits, surface-to-surface discretization can sometimes cause tangential motion of the slave surface as the overclosures are resolved. This tangential motion may have undesirable effects on a analysis. See “Modeling contact interference fits in ABAQUS/Standard,” Section 29.2.4, for more details on this situation.

The finite-sliding, surface-to-surface formulation is often better-suited than other contact formulations for modeling contact near corners. In the example shown in Figure 29.2.11–9, the slave surface is on the “outer” body (i.e., the body with a reentrant corner). With node-to-surface discretization a single constraint acts at the corner slave node in the “average” normal direction of the master surface, which often leads to poor resolution of contact, non-physical response, and even early termination of an analysis. However, surface-to-surface discretization generates two constraints near the corner for the respective faces, as shown in Figure 29.2.11–9, resulting in more stable contact behavior.