We now turn our attention to another class of material nonlinearity, namely, the nonlinear elastic response exhibited by rubber materials.

The stress-strain behavior of typical rubber materials, shown in Figure 8–16, is elastic but highly nonlinear. This type of material behavior is called hyperelasticity. The deformation of hyperelastic materials, such as rubber, remains elastic up to large strain values (often well over 100%). ABAQUS makes the following assumptions when modeling a hyperelastic material:

The material behavior is elastic.

The material behavior is isotropic.

The material is incompressible by default.

The simulation will include nonlinear geometric effects (NLGEOM will be used).

ABAQUS has a special family of “hybrid” elements that must be used to model the fully incompressible behavior seen in hyperelastic materials. These “hybrid” elements are identified by the letter `H' in their name; for example, the hybrid form of the 8-node brick, C3D8, is called C3D8H.

Elastomeric foams are another class of highly nonlinear, elastic materials. They differ from rubber materials in that they have very compressible behavior when subjected to compressive loads. They are modeled with a separate material model in ABAQUS and are not discussed in detail in this guide.

ABAQUS uses a strain energy potential (U), rather than a Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio, to relate stresses to strains in hyperelastic materials. Several different strain energy potentials are available: a polynomial model, the Ogden model, the Arruda-Boyce model, and the van der Waals model. Simpler forms of the polynomial model are also available, including the Mooney-Rivlin, neo-Hookean, reduced polynomial, and Yeoh models.

The polynomial form of the strain energy potential is the one that is most commonly used. Its form is

![]()

![]()

![]()

The other hyperelastic models are similar in concept and are described in “Hyperelasticity,” Section 10.5 of the ABAQUS Analysis User's Manual.

You must provide ABAQUS with the relevant material parameters to use a hyperelastic material. For the polynomial form these are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . It is possible that you will be supplied with these parameters when modeling hyperelastic materials; however, more likely you will be given test data for the materials that you must model. Fortunately, ABAQUS can accept test data directly and calculate the material parameters for you (using a least squares fit).

. It is possible that you will be supplied with these parameters when modeling hyperelastic materials; however, more likely you will be given test data for the materials that you must model. Fortunately, ABAQUS can accept test data directly and calculate the material parameters for you (using a least squares fit).

A convenient way of defining a hyperelastic material is to supply ABAQUS with experimental test data. ABAQUS then calculates the constants using a least squares method. The experimental tests for which ABAQUS can fit data are:

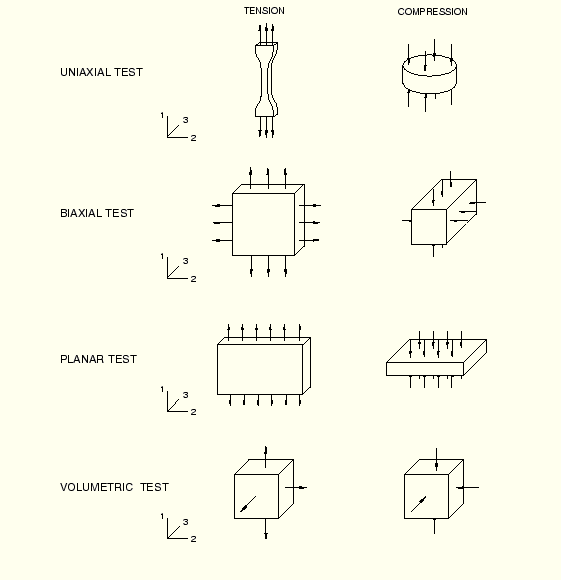

Uniaxial tension and compression.

Equibiaxial tension and compression.

Planar tension and compression (pure shear).

Volumetric tension and compression.

The deformation modes seen in these tests and the ABAQUS input options used to define the data for each are shown in Figure 8–17. Unlike plasticity data, the test data for hyperelastic materials must be given to ABAQUS as nominal stress and nominal strain values.

Figure 8–17 Deformation modes and ABAQUS input options for the various experimental tests for defining hyperelastic material behavior.

Volumetric compression data only need to be given if the material's compressibility is important. Normally it is not important, and the default fully incompressible behavior is used.

Achieving the best material model from your data

The quality of the results from a simulation using hyperelastic materials strongly depends on the material test data that you provide ABAQUS. Typical tests are shown in Figure 8–17. There are several things that you can do to help ABAQUS calculate the best possible material parameters.

Wherever possible, try to obtain experimental test data from more than one deformation state—this allows ABAQUS to form a much more accurate and stable material model. However, some of the tests shown in Figure 8–17 produce equivalent deformation modes for incompressible materials. The following are equivalent tests for incompressible materials:

Uniaxial tension ↔ Equibiaxial compression

Uniaxial compression ↔ Equibiaxial tension

Planar tension ↔ Planar compression

In addition, the following may improve your hyperelastic material model:

Obtain test data for the deformation modes that are likely to occur in your simulation. For example, if your component is loaded in compression, make sure that your test data include compressive, rather than tensile, loading.

Both tension and compression data are allowed, with compressive stresses and strains entered as negative values. If possible, use compression or tension data depending on the application, since the fit of a single material model to both tensile and compressive data will normally be less accurate than for each individual test.

Try to include test data from the planar test. This test measures shear behavior, which can be very important.

Provide more data at the strain magnitudes that you expect the material will be subjected to during the simulation. For example, if the material will only have small tensile strains, say under 50%, do not provide much, if any, test data at high strain values (over 100%).

Perform one-element simulations of the experimental tests and compare the results ABAQUS calculates to the experimental data. If the computational results are poor for a particular deformation mode that is important to you, try to obtain more experimental data for that deformation mode. These one-element simulations are very easy to perform in ABAQUS/CAE. Please consult the ABAQUS/CAE User's Manual for details.

Stability of the material model

It is common for the material model determined from the test data to be unstable at certain strain magnitudes. ABAQUS performs a stability check to determine the strain magnitudes where unstable behavior will occur and prints a warning message in the data (.dat) file. You should check this information carefully since your simulation may not converge if any part of the model experiences strains beyond the stability limits. The stability checks are done for specific deformations, so it is possible for the material to be unstable at the strain levels indicated if the deformation is more complex. Likewise, it is possible for the material to become unstable at lower strain levels if the deformation is more complex.