Difference between revisions of "WarmUp Boot"

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

And there you go - you now have a series of LEDs controlled by a nice little dial! Here is a video of it in action: | And there you go - you now have a series of LEDs controlled by a nice little dial! Here is a video of it in action: | ||

| − | [[File:PotentiometerTest.gif | + | [[File:PotentiometerTest.gif|caption]] |

== How To: Control a Heat Pad with a MOSFET and Potentiometer == | == How To: Control a Heat Pad with a MOSFET and Potentiometer == | ||

Revision as of 19:55, 2 May 2017

Contents

- 1 Team Members

- 2 Overview

- 3 Objectives

- 4 Challenges

- 5 Initial Design Sketches

- 6 Gantt Chart

- 7 Budget

- 8 Design + Solutions

- 9 How To: Create a Flashy, Blinking Turn-On Sequence for a Button with LEDs

- 10 How To: Control a Series of LEDs with a Potentiometer

- 11 How To: Control a Heat Pad with a MOSFET and Potentiometer

- 12 How To: Connect Two TMP102 Sensors to One Arduino Mega

- 13 References

Team Members

Jackson Kleeman, Class of 2019, Systems Engineer

Daniel Reiff, Class of 2019, Systems Engineer

Allen Salama, Class of 2019, Systems Engineer

Nathan Schmetter, TA

Overview

No matter how thick the socks and no matter how many foot warmers you stuff into your ski boot, there are some days when the conditions are just too brittle for comfort. We aim to solve this by developing a ski boot heater in which a battery pack fitted to the boot powers up two heating pads, one on the top of the foot and the other on the toes, meshed within the boot. And to ensure customization and to combat overheating, there will be a temperature gauge the user may interact with to adjust the temperature to his/her liking. This interface will also be fixed to the boot, and have thickness so that it may double as an encasing for the Arduino, circuits and breadboard. Each heating pad will be linked to a LED button, which lights up when clocked on, and an accompanying dial under each button to allow for the user to manually adjust the warmth of each pad. A row of 4-6 LED's will be located at the top of the interface to illustrate how hot each pad is.

Objectives

- To create an efficient closed loop system between the battery pack and heat pad that does not lose power[1]

- To prevent the boot from overheating

- To ensure that the panel boot warming system is waterproof and unaffected by the elements

- To create an efficient and elegant user interface that will allow for the wearer to control the temperature of each heating pad.[2]

Challenges

- Learning how to use Arduino in creating a user interface for temperature control

- Ensuring the general safety of our design, by eliminating exposed wires and ensuring a limited amount of current is supplied to the heat pads so that they do not overheat

- Encasing all exposed electrical components to not only make the product look more polished, but more importantly, to ensure the system is waterproof

- Learning how to 3-D print to create encasings for the interface and any exposed electrical components

- Ensuring there is enough voltage in our battery pack to power the heating pad, without compromising comfort or functionality of the ski boot

- Further down the road, we would like to see if we can add a solar panel component to our system as an additional means of charging the battery. Should we tackle this, figuring out how to attach the solar panel onto the ski in a way that is both strong yet matches the ski’s flexibility will be another challenge.

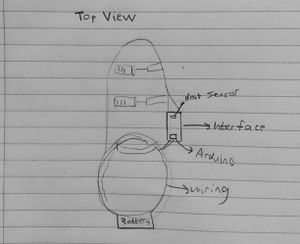

Initial Design Sketches

| Exterior | Interior | Top Down |

|---|---|---|

Gantt Chart

Budget

- Filament for 3d printer (provided)

- Arduino (provided)

- 5V heating pads (x2)- $9.90 ($4.95 each) https://www.sparkfun.com/products/11289

- Assorted LED Pack - $2.95 https://www.sparkfun.com/products/12062

- LED Tactile Button (x2) - $3.90 ($1.95 each) https://www.sparkfun.com/products/10443

- Silver Metal Knob (x2) - $3.00 ($1.50 each) https://www.sparkfun.com/products/10001

- N Channel MOFSET (x2)- $1.90 ($0.95 each) https://www.sparkfun.com/products/10213

- Diode 10 pack-$1.50 https://www.adafruit.com/products/755

- 10K ohm resistor 20 pack-$0.95 https://www.sparkfun.com/products/11508

- Digital Temperature Sensor Breakout (x2) -$9.90 ($4.95 each) https://www.sparkfun.com/products/13314

- 330 ohm resistor 30 pack- $0.95 https://www.sparkfun.com/products/11507

- Ski boots - $10 https://stlouis.craigslist.org/spo/5966731361.html

- 9V batteries - $8.79 https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0164F986Q/ref=ox_sc_act_title_1?ie=UTF8&smid=A192YN97ZBIJZL&th=1

- 9V Wall Adapter Power Supply - $5.95 https://www.sparkfun.com/products/298

- Adafruit 9V Battery Case w/ Switch and Barrel Connector - $3.95 http://www.robotshop.com/en/adafruit-9v-battery-case-switch-barrel-connector.html?gclid=CjwKEAiAlZDFBRCKncm67qihiHwSJABtoNIg8UX8WD3DJWL1M7AK0-IAY6HTO1l_bPe_HL9vlP54MRoCKuPw_wcB

- Gorilla Epoxy - $5.47 https://www.amazon.com/Gorilla-Epoxy-85-oz-Clear/dp/B001Z3C3AG

- Rotary Potentiometer 10k Ohm, Linear (x2) - $1.90 ($.95 each) https://www.sparkfun.com/products/9939

- Solderable Perf Board, 2-1/2 x 3-1/8" - $4.05 ($1.35 each) https://www.circuitspecialists.com/64-8933.html

Total: $71.01

Design + Solutions

3D Design for InteractiveInterface & Arduino/Circuit Housing, Arduino C/C++ Coding, Circuit Design to Link Heating Pads and Interface

| Module 1: 3D Design | Module 2: Coding | Module 3: Circuitry |

|---|---|---|

|

[[File:|thumbnail]] |

[[File:|thumbnail]] | |

| The design of the arduino housing and the front interface box in the back and front of the boot (respectively) was an important feature of our project. We needed to make 3D printed pieces that would stay secure to the boot in the event that the skier may fall. In order to do that we needed to maximize the point of contact between the housings and the boot. This required the use of a 3D scanner to replicate the surface of the boot, allowing us to design housings that fit the shape of the boot perfectly. | The coding was broken down into three key pieces across the actual heating aspect and creating the interactive interface: (1) Physically heating up the pads with their own MOSFET and potentiometer (explained in the tutorials below), (2) Using the same potentiometer to light up a series of LEDs to indicate the power level of the MOSFET, and in turn, the level of the heating pad, and (3) Incorporating two buttons to the each heating pad system to turn it on and off, plus creating a flashy light-up sequence upon turning on the button. | circuit module goes here |

How To: Create a Flashy, Blinking Turn-On Sequence for a Button with LEDs

Initially, we were going to use nifty buttons with built-in LEDs to indicate that the system was on and running, but unfortunately we found that the leads for the LED part of the button were super flimsy and would turn would break easily upon soldering. So we had to think creatively to come up with another to indicate to the user that the system was turned on in the interface, so we turned our attention to the row of LEDs already being used to indicate the heat level of the pads. With quite a bit of ease, we were able to have them blink in fun sequence in response to the button being pressed. Now, allow us to teach you how to do the same!

Materials: Arduino Mega board, Tactile pushbutton (easily found on Sparkfun), one 10kΩ resistor, four 220Ω resistors, 4 LEDs, wires

Step 1: Connect the button. This we took directly from Arduino’s tutorial, which can be found here (the resistor seen is a 10kohm resistor). The placement of the button pin is up to you, as long as it is connected to a digital pin.

Step 2: Now time for the coding! It is a very simple bit of code, which is can be found here. Read through the comments to get a full understanding of it, and make sure that the declaration of buttonPin matches the digital pin on the Arduino that your button is connected to.

Step 3: Now that the button is connected to the board, it is time to add our LED lights, along with their resistors. For our project, we used 4, as seen in the circuit diagram.

Make sure that at the end of each LED resistor, a wire runs from a pin parallel to the resistor lead and into a digital pin on the Arduino Mega.

Step 4: More code! You can find it here, but we are really just building off the original button code, only with a couple additions:

- Initialization of the LEDs onto the Arduino (same as for the button)

- Declaring the LEDs as “Outputs” in the void setup (as the button is declared as an Input)

- Including a for loop inside the if statement portion in which the button and system are turned on.

- Once the for loop conditions are set, the blinking sequence is really up to you. Just write “digitalWrite(led_, HIGH) to turn the LED of your choice on, and add a very small delay in between the next course of action

- Also make sure to include “digitalWrite(led_, LOW)” for each LED under the else if condition where the system is off, just to ensure that every light is off when the system is off

And that’s it - go blink away!

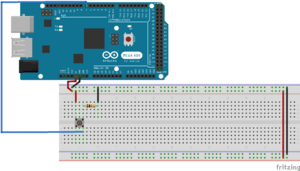

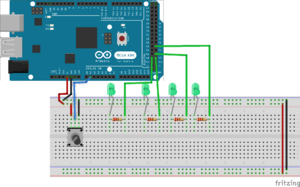

How To: Control a Series of LEDs with a Potentiometer

Now that we have a button working, as well as an indication for our user on the interface that the system is on, we will use those LEDs to indicate the power level of the heat pad. For the sake of this tutorial, as well as to emulate the process we went through during our project, we will forgo the heat pad and simply focus on using a potentiometer (essentially a dial) to light up a series of LEDs.

Materials: Arduino board, four LEDs and 220Ω resistors (the quantity is really up to you), potentiometer (we used these), wires

Step 1: Hook up the circuit elements as shown. Technically, either end of the three-pin potentiometer (the middle one runs to the Arduino) can be positive or negative, it will just affect which way your potentiometer “turns.” In other words, it will dictate whether turning the potentiometer clockwise or counterclockwise lights up the LEDs.

Step 2: The code! You may download it from here. Several similarities can be drawn from the code for the button, such as:

- Initializing the LEDs and potentiometer (this time to an analog pin) with the “const int” function

- In the void setup, declaring the LEDs as “Outputs” and the potentiometer as an “Input”

- Reading the position of the input, in this case, the potentiometer

The only differences we see in this code are:

- Using the analogRead() function instead digitalRead() to read the position of the potentiometer

- The usage of the map() function

- Potentiometers read from a scale of 0-1023, with 1023 being fully “on.” However, when delivering variable current to many resistor-based devices (such as our heating pads), they typically use pulse-width modulation, or PWM, and these are read on a 0-255, with 255 being fully “on.”

- This is precisely where the map() function comes into play. It takes whatever position the potentiometer is on the 0-1023 and simply “maps,’ or translates, it into the conventional 0-255 scale.

And there you go - you now have a series of LEDs controlled by a nice little dial! Here is a video of it in action:

How To: Control a Heat Pad with a MOSFET and Potentiometer

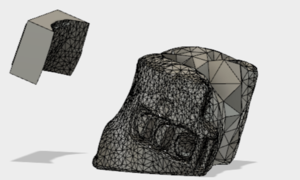

Step 1: Chose the parts of the boot where you want to attach your housings. We chose the parts shaded blue in picture A because putting our housings at those two points would not impede the skier’s range of motion and because these two places had enough surface area to make a big enough point of contact between the boot and the housings, allowing for a more secure connection.

Step 2: Once you have decided where you want the housings to go, take a spare, identical boot and a jigsaw to cut out the parts of the boot where the housings would attach. Make sure that the parts you cut out are less than a foot tall and less than 9 inches wide, so as to assure that the entire part will fit in the Matter and Form 3D scanner.

Step 3: Download the necessary Matter and Form 3D scanner software for free off the company’s website and plug the scanner into your computer.

Step 4: Open the Matter and Form program on your computer and place the calibration cube (shown in picture B) in the center of the rotating scanning plate when prompted by the software. This will assure that you will get a more accurate, detailed scan of your parts.

Step 5: Once the scanner is done calibrating, the scanner’s software will prompt you to place the parts you desire to scan on the rotating scanning plate and tell the software to begin scanning.

Step 6: Once the scan is completed, upload the scan file to Fusion 360. When you open the file on Fusion 360, the part will not have the multi-triangle surface that it does in picture C. To get the multi-triangle surface, select the scan by highlighting it. Then go to the “sculpt” pull-down menu on the Fusion 360 toolbar and select “Mesh” and choose to change the surface of the part to “T-Spline.”

Step 7: Create a new design on Fusion 360 and create a cube with the dimensions of the height and width you wish to make your connection surface between the housing and the boot.

Step 8: Go back to your reworked scan file, and in your design library on the left hand side of the Fusion 360 page, right click on the cube and select “insert into current design.”

Step 9: Once the cube is in the same frame as the reworked scan, align the cube so that the cube where you want the housing to be placed. Make sure that there is overlap between the two parts. The surface area of the scan that the cube overlaps is going to drive the cut made to the cube.

Step 10: Go to the toolbar and click the “modify” pull-down menu. Choose “combine,” select the cube for the “target body” and the scanned part for the “tool body.” For the choice of “operation” select “cut.” Click ok and the cube should now have a side with a surface that matches the surface of the scanned part like shown in picture D.

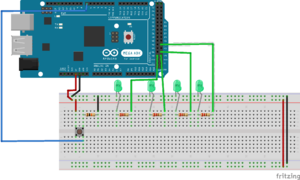

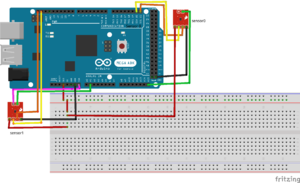

How To: Connect Two TMP102 Sensors to One Arduino Mega

Since the each circuit for each heating pad was identical, we initially stuck to working with and debugging one, knowing ti wold be the same for the second pad. However, something we learned along the way is that connecting multiple TMP102 sensors to an Arduino Mega board required some extra work. This is how we had to do it.

Materials: Arduino Mega board, two TMP102 sensors (found here), wires (it helps to solder them to the sensor leads first)

Step 1: Start with one TMP102 sensor. We followed the TMP102 Breakout Guide found on Sparkfun’s website on an Arduino Uno board, and it worked like a charm. Do this to familiarize yourself, and make sure to download the “SparkfunTMP102.h” library and import it into your Arduino (“Sketch” -> “Include Library” -> “Add .ZIP Library”) before copying and pasting the code.

- Notice how only 5 of the 6 pins of the sensor are connected. The 6th one is the ADD0 pin, which essentially sets the address of the sensor. The default address is already embedded as (0x48), so your first sensor does not need this. This pin will be used in the second (and any subsequent) TMP102 sensors.

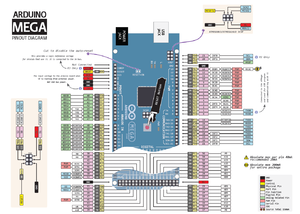

Issues arose when trying to transfer what he had just done onto an Arduino Mega board, since the library is designed for specifically Arduino Uno boards. Nathan was instrumental in helping us with this, but the process is actually not too difficult. It first starts with observing the pinout diagram for an Arduino Mega board.

Step 2: Construct the new circuit diagram as shown. Leave the first TMP102 as it was connected previously, except this time, connect the “3V3” pin from the Arduino Mega onto a breadboard, as both sensors need this and there is only one of these pins on the board. Then use this code

- The rest of the connections are easy. There are enough “GND,” “SCL,” (orange wires) and “SDA,” (yellow wires) pins on the Arduino Mega for the sensor to fit, as well as a ton of Analog pins (green wires) for the “ALT” (Alert) leads.

- Note the pink wire on the second sensor. This is the ADD0 pin, and it needs to be connected to a pin on the board and its address needs to changed from (0x48) in the code, which can be found [here]

- The specific pin to connect to is the “VIN” pin, and in the code, you need to initialize it (before the void setup code) as “TMP102 sensor1(0x49)”.

Step 3: Aside from that initialization, the rest of the mimics the code found on the Sparkfun website in Step 1. You should now see printed temperature values and alert states for both sensor, simultaneously!

References

- ↑ Coding Heating Pads with Arduino Uno, https://astronomersanonymous.wordpress.com/2016/04/02/controlling-heating-pads-with-arduino-uno/

- ↑ Make Your Own Temperature Controller with an Arduino http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/make-your-own-temperature-controller-with-an-arduino/