Difference between revisions of "Sudoku Constraint Propagation"

(Created page with "===Constraint Propagator=== {{CodeToImplement|DefaultConstraintPropagator|createCandidateSetsFromGivens<br>createNextCandidateSets<br>assign<br>eliminate|sudoku.lab}} You wi...") |

|||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

====eliminate(resultOptionSets,square,value)==== | ====eliminate(resultOptionSets,square,value)==== | ||

{{Sequential|private void eliminate(Map<Square, SortedSet<Integer>> resultOptionSets, Square square, int value)}} | {{Sequential|private void eliminate(Map<Square, SortedSet<Integer>> resultOptionSets, Square square, int value)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===(Optional) Advanced Constraint Propagation=== | ||

| + | ====Unit Constraint Propagation==== | ||

| + | The second rule in [http://norvig.com/sudoku.html Peter Norvig's Essay] is Unit Constraint Propagation: "If a unit has only one possible place for a value, then put the value there". This propagation rule is it bit more challenging to put into code, but doing so can make even the hardest of Sudoku puzzles fall nice and quickly. To complete this bonus part of the lab, simply update your <code>assign</code> and <code>eliminate</code> methods to do unit constraint propagation (don't remove the old propagation rule!). After assigning a square, you'll have to look at the new options set to see if any unit (a single row, column, or box) has only one unassigned square that is a possibility for any value. We encourage you to think of a solution on your own! Below is a example of unit constraint propagation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Board !! Info | ||

| + | |- | ||

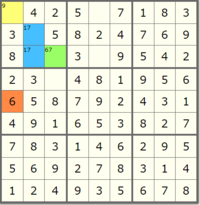

| + | | [[File:UnitConstraint1.PNG|200px]] || We can see that the red square (E1) has only one available option. At this point, let's say we call assign on the red square E1 for the value 6. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[File:UnitConstraint2.PNG|200px]] || Due to the assignment of red square E1, the value of 6 is eliminated from its peer, yellow square A1. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[File:UnitConstraint3.PNG|200px]] || Our Peer Elimination constraint propagation will treat yellow square A1 as if it has been assigned. Unfortunately, eliminating the value 9 from the peers doesn't open up any new opportunities for solving squares. This is where unit constraint propagation kicks in. Of the three unassigned squares in the top left box unit, 6 is only a valid option in the green square, C3. Even though green square C3 has multiple possible options remaining, we know that it '''must''' be 6, and should assign it as such | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[File:UnitConstraint4.PNG|200px]] || Once green square C3 has been assigned (all other options are removed), we should make sure that all of C3's peers have 6 removed from their options. And keep an eye out for any new squares that we now know due to the two propagation rules! With both peer elimination and unit constraint propagation, we can solve a large quantity of Sudoku puzzles without needing any backtracking recursion | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Naked Twins==== | ||

| + | In what is dubbed a [http://www.sudokudragon.com/sudokustrategy.htm more sophisticated strategy] in [http://norvig.com/sudoku.html Peter Norvig's Essay] is Naked Twins strategy which ''"looks for two squares in the same unit that both have the same two possible digits. Given {'A5': '26', 'A6':'26', ...}, we can conclude that 2 and 6 must be in A5 and A6 (although we don't know which is where), and we can therefore eliminate 2 and 6 from every other square in the A row unit. We could code that strategy in a few lines by adding an elif len(values[s]) == 2 test to eliminate."'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Tips==== | ||

| + | *Make sure your solver uses the generic SquareSearchAlgorithm so that it works with both versions of the search ordering. | ||

| + | *Just like n-queens, your <code>solveKernel</code> is the recursive method that will be called in the solve method. Again, watch where you put your <code>finish</code>. | ||

| + | *In your <code>solveKernel</code> method, you should use the given search algorithm (row major or fewest options first) to select which square you will fill. After selecting a square, you should recursively call the kernel to check every viable option in the context of the puzzle. If there are no more unfilled squares, you should set the value of the solution to the finished puzzle and exit out of the recursion. | ||

Latest revision as of 21:50, 24 September 2021

Constraint Propagator

| class: | DefaultConstraintPropagator.java | |

| methods: | createCandidateSetsFromGivens createNextCandidateSets assign eliminate |

|

| package: | sudoku.lab | |

| source folder: | student/src/main/java |

You will need to implement two public methods to satisfy the ConstraintPropagator interface: createCandidateSetsFromGivens and createNextCandidateSets. Each of these two methods will be invoked from a different constructor in the #DefaultImmutableSudokuPuzzle class. It should be relatively obvious which one goes with which based on the parameters.

createCandidateSetsFromGivens

method: public Map<Square, SortedSet<Integer>> createCandidateSetsFromGivens(String givens) ![]() (sequential implementation only)

(sequential implementation only)

This method will be invoked when you have loaded a new puzzle. Whether it is from the newspaper, or your airline magazine, or Dr. Arto Inkala there is a set of givens the puzzle creator has provided. That string of givens is parsed into a Map from Square to Optional<Integer>. If a square is given (that is it has a specified starting value) the Optional will be present and its value will be set. If a specific spot of the board wasn't given in the input, it will be empty.

new EnumMap<>(Square.class) for an EnumMap of Squares. |

A good approach here is to start of by initializing all of the squares to all the options (1 through 9) whether or not the square has a given value.

Square.values() is useful here for iterating over all of the Square enum constants. |

CandidateSet.createAllCandidates() is useful here when looking to start a square's candidates off at [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. |

Once that is complete go through the givens and get your private method(s) to work for you.

createNextCandidateSets

method: public Map<Square, SortedSet<Integer>> createNextCandidateSets(Map<Square, SortedSet<Integer>> otherCandidateSets, Square square, int value) ![]() (sequential implementation only)

(sequential implementation only)

This method should be invoked when you are searching for the solution in your solver. Much like when you need to create a new copy of the board every time you make a decision in the n-queens search so too will you need to create a new copy of your sudoku board every time you make a decision in your backtracking search.

Make sure to use the SudokuUtils.deepCopyOf method and refrain from mutating the incoming parameter otherCandidateSets.

As warned above, do not actually do any of the constraint propagation in this method. Simply get the copy of the options set, then leverage your private assign method (which in turn may leverage eliminate) to update the copy to be correct before returning it.

a and b, and you set a = b, then any changes you make to a will also be made to b. Both variables reference the same objects; they are not copies. |

Assign and Eliminate

Background

Peter Norvig's Essay is very helpful here. We have adopted his terms, but challenge yourself to complete this section without simply translating his pseudocode.

To simplify things a bit, we have elected to not short circuit when a 0 option square is found (relying on the search ordering to take care of that for us).

It is up to you how to utilize these two methods. The goal is to update the map that is passed in to reflect the "solving" of a square. For example, if assign is called on square A1 for the value 1, the map that is returned should link the square A1 to a list containing just the value 1 ([1]). Furthermore, any square that is a peer of A1 (ex. B1), should not have the value 1 in its set in the map.

But in solving Sudoku, there are some strategies that we can rely on to more efficiently complete the puzzle. The first one, and required in order to finish this lab, is Peer Elimination Constraint Propagation (rule 1 in the Norvig essay). The rule is as follows: "If a square has only one possible value, then eliminate that value from the square's peers."

Let's very slowly walk through a example of this propagation in detail to make it more clear what we are looking for. Start by looking at this nearly finished board:

Two Paths

All Assign All The Time

In this implementation, you will perform all of your work in the assign method. eliminate will never be invoked.

Mutual Recursion

In this implementation, assign and eliminate will take on their own roles, at times calling each other. This implementation leads nicely into the extra credit portion.

assign(resultOptionSets,square,value)

method: private void assign(Map<Square, SortedSet<Integer>> resultOptionSets, Square square, int value) ![]() (sequential implementation only)

(sequential implementation only)

eliminate(resultOptionSets,square,value)

method: private void eliminate(Map<Square, SortedSet<Integer>> resultOptionSets, Square square, int value) ![]() (sequential implementation only)

(sequential implementation only)

(Optional) Advanced Constraint Propagation

Unit Constraint Propagation

The second rule in Peter Norvig's Essay is Unit Constraint Propagation: "If a unit has only one possible place for a value, then put the value there". This propagation rule is it bit more challenging to put into code, but doing so can make even the hardest of Sudoku puzzles fall nice and quickly. To complete this bonus part of the lab, simply update your assign and eliminate methods to do unit constraint propagation (don't remove the old propagation rule!). After assigning a square, you'll have to look at the new options set to see if any unit (a single row, column, or box) has only one unassigned square that is a possibility for any value. We encourage you to think of a solution on your own! Below is a example of unit constraint propagation.

Naked Twins

In what is dubbed a more sophisticated strategy in Peter Norvig's Essay is Naked Twins strategy which "looks for two squares in the same unit that both have the same two possible digits. Given {'A5': '26', 'A6':'26', ...}, we can conclude that 2 and 6 must be in A5 and A6 (although we don't know which is where), and we can therefore eliminate 2 and 6 from every other square in the A row unit. We could code that strategy in a few lines by adding an elif len(values[s]) == 2 test to eliminate."

Tips

- Make sure your solver uses the generic SquareSearchAlgorithm so that it works with both versions of the search ordering.

- Just like n-queens, your

solveKernelis the recursive method that will be called in the solve method. Again, watch where you put yourfinish. - In your

solveKernelmethod, you should use the given search algorithm (row major or fewest options first) to select which square you will fill. After selecting a square, you should recursively call the kernel to check every viable option in the context of the puzzle. If there are no more unfilled squares, you should set the value of the solution to the finished puzzle and exit out of the recursion.