The first step in defining contact between two structures in ABAQUS/Standard is to create surfaces. Next, contact interactions are created to pair the surfaces that may contact each other. Then you define the mechanical property models that govern the behavior of the surfaces when they are in contact.

Define possible contact between two surfaces in an ABAQUS/Standard simulation by assigning the surface names to a contact interaction. Each contact interaction must refer to a contact property, in much the same way that each element must refer to an element property. Constitutive behavior, such as the contact pressure-clearance relationship and friction, can be included in the contact property.

When you define a contact interaction, you must decide whether the magnitude of the relative sliding will be small or finite. The default is the more general finite-sliding formulation. The small-sliding formulation is appropriate if the relative motion of the two surfaces is less than a small proportion of the characteristic length of an element face. Using the small-sliding formulation when applicable results in a more efficient analysis.

ABAQUS/Standard uses a pure master-slave contact algorithm: nodes on one surface (the slave) cannot penetrate the segments that make up the other surface (the master), as shown in Figure 12–7. The algorithm places no restrictions on the master surface; it can penetrate the slave surface between slave nodes, as shown in Figure 12–7.

A consequence of this strict master-slave formulation is that you must be careful to select the slave and master surfaces correctly to achieve the best possible contact simulation. Some simple rules to follow are:

the slave surface should be the more finely meshed surface; and

if the mesh densities are similar, the slave surface should be the surface with the softer underlying material.

When using the small-sliding formulation, ABAQUS/Standard establishes the relationship between the slave nodes and the master surface at the beginning of the simulation. ABAQUS/Standard determines which segment on the master surface will interact with each node on the slave surface. It maintains these relationships throughout the analysis, never changing which master surface segments interact with which slave nodes. If geometric nonlinearity is included in the model, the small-sliding algorithm accounts for any rotation and deformation of the master surface and updates the load path through which the contact forces are transmitted. If geometric nonlinearity is not included in the model, any rotation or deformation of the master surface is ignored and the load path remains fixed.

The finite-sliding contact formulation requires that ABAQUS/Standard constantly determine which part of the master surface is in contact with each slave node. This is a very complex calculation, especially if both the contacting bodies are deformable. The structures in such simulations can be either two- or three-dimensional. ABAQUS/Standard can also model the finite-sliding self-contact of a deformable body. Such a situation occurs when a structure folds over onto itself.

The finite-sliding formulation for contact between a deformable body and a rigid surface is not as complex as the finite-sliding formulation for two deformable bodies. Finite-sliding simulations where the master surface is rigid can be performed for both two- and three-dimensional models.

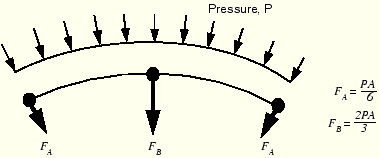

When selecting elements for contact analyses in ABAQUS/Standard, it is better, in general, to use first-order elements for those parts of a model that will form a slave surface. Second-order elements can sometimes cause problems in contact simulations because of the way these elements calculate consistent nodal loads for a constant pressure. The consistent nodal loads for a constant pressure, P, on a second-order, two-dimensional element with area A are shown in Figure 12–8.

Figure 12–8 Equivalent nodal loads for a constant pressure on a two-dimensional, second-order element.

The contact algorithms base important decisions on the forces acting on the slave nodes. It is difficult for the algorithms to tell if the force distribution shown in Figure 12–8 represents a constant contact pressure or an actual variation across the element. The equivalent nodal forces for a three-dimensional, second-order brick element are even more confusing because they do not even have the same sign for a constant pressure, making it very difficult for the contact algorithm to work correctly, especially for nonuniform contact. Therefore, to avoid such problems, ABAQUS/Standard automatically adds a midface node to any face of a second-order, three-dimensional brick or wedge element that defines a slave surface. The equivalent nodal forces for a second-order element face with a midface node have the same sign for a constant pressure, although they still differ considerably in magnitude.

The equivalent nodal forces for applied pressures on first-order elements always have a consistent sign and magnitude; therefore, there is no ambiguity about the contact state that a given distribution of nodal forces represents.

If your geometry is complicated and requires the use of an automatic mesh generator, the modified second-order tetrahedral elements (C3D10M) in ABAQUS/Standard should be used. These elements are designed to be used in complex contact simulations; regular second-order tetrahedral elements (C3D10) have zero contact force at their corner nodes, leading to poor predictions of the contact pressures. They should, therefore, not be used in contact problems. The modified second-order tetrahedral elements can calculate the contact pressures accurately.

Understanding the algorithm ABAQUS/Standard uses to solve contact problems will help you understand the diagnostic output in the message file and carry out contact simulations successfully.

The contact algorithm in ABAQUS/Standard, which is shown in Figure 12–9, is built around the Newton-Raphson technique discussed in Chapter 8, “Nonlinearity.”

ABAQUS/Standard examines the state of all contact interactions at the start of each increment to establish whether slave nodes are open or closed. In Figure 12–9,Before checking for equilibrium of forces or moments, ABAQUS/Standard first checks for changes in the contact conditions at the slave nodes. Any node where the clearance after the iteration becomes negative or zero has changed status from open to closed. Any node where the contact pressure becomes negative has changed status from closed to open. If any contact changes are detected in the current iteration, ABAQUS/Standard labels it a severe discontinuity iteration and no equilibrium checks are carried out.

ABAQUS/Standard modifies the contact constraints to reflect the change in contact status after the first iteration and tries a second iteration. ABAQUS/Standard repeats the procedure until an iteration is completed with no changes in contact status. This iteration becomes the first equilibrium iteration, and ABAQUS/Standard performs the normal equilibrium convergence checks. If the convergence checks fail, ABAQUS/Standard performs another iteration. Every time a severe discontinuity iteration occurs, ABAQUS/Standard resets the internal count of equilibrium iterations to zero. This iteration count is used to determine if an increment should be abandoned due to a slow convergence rate. ABAQUS/Standard repeats the entire process until convergence is achieved, as summarized in Figure 12–9.

The summary for each completed increment in the message and status files shows how many iterations were severe discontinuity iterations and how many were equilibrium iterations. The total number of iterations for an increment is the sum of these two.

By separating the two types of iterations, you can see how well ABAQUS/Standard is coping with the contact calculations and how well it is achieving equilibrium. If the number of severe discontinuity iterations is high but there are few equilibrium iterations, ABAQUS/Standard is having difficulty determining the proper contact conditions. By default, ABAQUS/Standard abandons any increment where it needs more than twelve severe discontinuity iterations and tries the increment again with a smaller increment size. If there are no severe discontinuity iterations, the contact state is not changing from increment to increment.