Products: ABAQUS/Standard ABAQUS/CAE

This section highlights the difficulties that are most commonly encountered when modeling contact interactions with ABAQUS/Standard. Recommendations on how to circumvent these problems are presented.

When defining three-dimensional surfaces for use in finite-sliding applications, avoid defining two surface nodes with the same coordinates. Such a definition can give rise to a seam, or crack, in the surface as shown in Figure 21.2.9–1.

If viewed with the default plotting options in ABAQUS/CAE, this surface will appear to be a valid, continuous surface; however, if this surface is used as the master surface, a slave node sliding along the surface may fall through this crack and get “stuck” behind the master surface. Typically, convergence problems will result that may cause ABAQUS/Standard to terminate the analysis.Use the edge display options in the Visualization module of ABAQUS/CAE to identify any unwanted cracks in the surfaces used in the model. The cracks will appear as extra perimeter lines in the interior of the surface. Duplicate nodes can be avoided easily by equivalencing nodes when creating the model in a preprocessor.

When modeling finite-sliding contact, ensure that the master surface definition extends far enough to define the surface for all expected motions of the contacting parts of the model. Contact along the perimeter of master surfaces should be avoided. ABAQUS/Standard assumes that the mating slave surface nodes can fall off the free edge of the master surface, which can cause problems if a slave node wraps around and approaches its mating master surface from behind. Figure 21.2.9–2 illustrates appropriate and inappropriate master surface definitions.

A slave node that falls off a master surface in one iteration may find itself contacting the surface in the very next iteration; this phenomenon is known as chattering. If chattering continues, ABAQUS/Standard may not be able to find a solution. Request detailed contact printout to the message (.msg) file to monitor the history of a slave node that might slide off the master surface (see “The ABAQUS/Standard message file” in “Output,” Section 4.1.1). The message file output will show the cyclic opening and closing of contact at a slave node, which will indicate where the master surface needs to be modified.In such instances you can extend the master surface beyond the perimeter of the physical body that it approximates. Chattering can also occur with some contact elements, such as slide line and rigid surface contact elements. Slide line contact elements can also be extended. See “Extending master surfaces and slide lines,” Section 21.2.6, for details.

Falling off the edge of a master surface in small-sliding contact problems is not an issue since slave nodes do not slide on the actual surface of the model. Instead, each slave node interacts with a flat, infinite contact plane. This plane is associated with the set of master surface nodes that are closest to the slave node in the undeformed configuration. For details about the small-sliding contact formulation, see “Contact formulation for ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 21.2.2.

Several problems are caused by surfaces created on very coarse meshes.

When a coarsely discretized surface is used as a slave surface, the master surface nodes can grossly penetrate the slave surface (see Figure 21.2.1–2). This situation is common when nonmatching meshes come into contact. To define contact accurately, use a refined mesh to create the slave surface.

Coarsely discretized, curved master surfaces in small-sliding simulations can lead to unacceptable solution accuracy due to the approximate nature of the “master planes.” Using a more refined mesh to define the master surface will improve the overall accuracy of the solution in small-sliding problems. However, unless perfectly matching meshes are used, local oscillations in the contact stress may still be observed, even in refined models.

The small-sliding contact formulation is more sensitive than the finite-sliding formulation to initial local gaps at the interface caused by mismatched meshes. In the small-sliding formulation each slave node interacts with a contact plane defined from the finite element approximation of the master surface, as discussed in “Contact formulation for ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 21.2.2. ABAQUS/Standard can define these planes only when each slave node can be projected onto the master surface. For initially nonmatching meshes you can improve the accuracy of the small-sliding contact pair by having ABAQUS/Standard adjust the position of the slave surface to ensure that all slave nodes that should initially be in contact with the master surface start out in contact (see “Adjusting the surfaces in a contact pair” in “Adjusting initial surface positions and specifying initial clearances in ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 21.2.3). Having these slave nodes start the simulation contacting the master surface allows ABAQUS/Standard to form the most accurate contact planes for the slave nodes. When the initial clearance or overclosure is very small compared to typical dimensions of the bodies in contact, you can specify these values precisely (see “Defining a precise initial clearance or overclosure” in “Adjusting initial surface positions and specifying initial clearances in ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 21.2.3).

Inaccurate local results may occur if second-order heat transfer elements are used to model a thermal interface and the meshes do not match across the surfaces. The worst results will be obtained when the midside node of an element on one surface is closest to the corner node of an element on the other surface. If a nonmatching mesh must be used in the model, use first-order elements or use a more refined mesh.

Nonuniform contact pressure distributions are likely to occur when very different mesh densities are used on the two deformable surfaces making up a contact pair. The nonuniformity can be particularly pronounced when “hard” contact is modeled and both surfaces are modeled with second-order elements, including modified, second-order tetrahedral elements. In such cases oscillations and “spikes” in the contact pressure may occur. Smoother contact pressures may be obtained for surfaces modeled with second-order elements by using penalty-type contact constraint enforcement (see “Contact pressure-overclosure relationships,” Section 22.1.2).

For second-order axisymmetric elements the contact area is zero at a node lying on the symmetry axis ![]() . To avoid numerical singularity problems caused by a zero contact area, ABAQUS/Standard calculates the contact area as if the node were a small distance from the symmetry axis. This may result in inaccurate local contact stresses calculated for nodes located on the symmetry axis.

. To avoid numerical singularity problems caused by a zero contact area, ABAQUS/Standard calculates the contact area as if the node were a small distance from the symmetry axis. This may result in inaccurate local contact stresses calculated for nodes located on the symmetry axis.

Contact of a surface with itself (self-contact) is provided for cases in which the original geometry is very different from the (deformed) geometry at which contact takes place. It would then be difficult for you to predict which parts of the surface will come into contact with each other. Where possible, it is always computationally more economical to declare parts of the surface as master and parts as slave. The same unpredictability makes it impossible to determine a priori which side will be the master and which side the slave. Therefore, ABAQUS/Standard uses a symmetric contact model: every single node of the surface can be a slave node and can simultaneously belong to master segments with respect to all other nodes.

It is possible that ABAQUS/Standard will report one of the sides of the contact interface as open and the other as closed. Typically this is caused because the surface is smoothed when it acts as the master surface and stays faceted when it acts as the slave surface. The shape or relative mesh refinement of the two regions of the surface that are in contact can also cause ABAQUS/Standard to report one of the sides as open and the other as closed.

It can be difficult to interpret the results from self-contact. Both sides at an interface are slave surfaces so each has results associated with it. The problem is that the results for contact pressure are not independent of each other; the contact pressure on one side will not necessarily be equivalent to the pressure on the other. The total contact pressure acting on both sides is the sum of the contact pressures on each side of the interface. Frictional slip is calculated independently for each side, based on the contact pressure for that side and the friction coefficient. Limits on the frictional shear stress, such as ![]() (see “Using the optional shear stress limit” in “Frictional behavior,” Section 22.1.4), may not be applied correctly because the contact pressure acting on each side will be less than the contact pressure calculated if the model had a master-slave contact pair.

(see “Using the optional shear stress limit” in “Frictional behavior,” Section 22.1.4), may not be applied correctly because the contact pressure acting on each side will be less than the contact pressure calculated if the model had a master-slave contact pair.

When defining contact, do not overconstrain the model. An overconstraint occurs when a contact constraint on the displacements, temperatures, electrical potentials, or pore fluid pressure at a slave node conflicts with a prescribed boundary condition or other kinematic constraint on that degree of freedom at the node. Specified boundary conditions on the master surface nodes typically do not cause overconstraints. Specified boundary conditions on slave nodes may create an overconstraint (see “Overconstraint checks,” Section 20.6.1); they will almost always create an overconstraint in tied contact pairs. Figure 21.2.9–4 illustrates slave node 101 fixed by a boundary condition in the contact direction. The model will be overconstrained only when the master surface comes in contact with slave node 101. Overconstraints can also occur if displacements tangential to the contact surface are held fixed and the Lagrange or the “rough” friction model (see “Frictional behavior,” Section 22.1.4) is used. For example, an overconstraint exists if the surface interaction model for the contact pair in Figure 21.2.9–4 uses Lagrange friction and the boundary condition on node 101 fixes the displacement in the ![]() -direction.

-direction.

“Zero pivot” and “numerical singularity” warning messages indicate which nodes are overconstrained in a model. Occasionally overconstraints do not create warning messages; this does not necessarily mean that the overconstraints have not adversely affected the analysis.

If nodes in a contact pair are overconstrained, contact forces become indeterminate and may become excessively high, particularly in tied contact pairs. Check the time average force (or moment, or flux) reported in the message file, or use ABAQUS/CAE to view the diagnostic information interactively (for more information, see Chapter 23, “Viewing diagnostic output,” of the ABAQUS/CAE User's Manual). If it is many orders of magnitude larger than the residual forces (or moments, or fluxes), an overconstraint may have occurred, and there is no guarantee that ABAQUS/Standard has found the correct solution. Another sign that the model is overconstrained is that the analysis begins to converge in a single iteration in every increment when the nonlinearities should require at least several iterations. Overconstraints can be avoided only by changing the contact definition or the boundary conditions.

In many common cases where overconstraints are defined, such as boundary conditions applied at contact slave nodes, ABAQUS/Standard can automatically detect the overconstraint and issue a warning message indicating the detected problem. For some often-encountered consistent overconstraint cases, ABAQUS/Standard automatically removes the unneeded constraint. For a detailed description of the automatic overconstraint handling, see “Overconstraint checks,” Section 20.6.1.

Overconstraint is not an issue when two or more overlapping slave surfaces interact with the same master surface and share the same contact property definition. ABAQUS/Standard recognizes this case and automatically ensures that the contact constraints in the overlap regions are not enforced multiple times. Overconstraint problems may also be alleviated by using the augmented Lagrangian contact constraint enforcement method (see “The augmented Lagrangian method in ABAQUS/Standard” in “Contact pressure-overclosure relationships,” Section 22.1.2).

Multi-point constraints (see “General multi-point constraints,” Section 20.2.2) and linear constraint equations (see “Linear constraint equations,” Section 20.2.1) place constraints on the dependent nodal degrees of freedom. In general, they should not be used to eliminate kinematic degrees of freedom at nodes that are part of a slave surface that may come into contact. If surface-based tie constraints are used to eliminate degrees of freedom at contact slave nodes, ABAQUS/Standard will automatically resolve the overconstraints at these nodes (see “Overconstraint checks,” Section 20.6.1).

Rigid body motion is generally not a problem in dynamic analysis. In static problems rigid body motion occurs when a body is not sufficiently restrained. “Numerical singularity” warning messages and very large displacements indicate unconstrained motion in a static analysis. Therefore, if contact pairs are used to constrain rigid body motion in static problems, ensure that the appropriate surface pairs are initially in contact. If necessary, define the model geometry to give a small initial overclosure to the contact pair, or use boundary conditions to move the structures into contact in the first step. The boundary conditions, which are unnecessary in subsequent steps, can be removed after the body is adequately constrained through contact with other components. Similarly, if a rigid body is meant to translate only, constrain its rotational degrees of freedom.

Frictional sticking can constrain rigid body motion. However, contact pressure must develop before friction can be generated. Therefore, friction is not effective in constraining rigid body motion when surfaces first come into contact. You must temporarily eliminate rigid body motion by defining a boundary condition or by grounding the body with soft springs or dashpots.

ABAQUS/Standard offers two capabilities that automatically control rigid body motions in static problems before contact closure and friction restrain such motions. You can activate either capability in a particular step.

These capabilities are meant to be used in cases in which it is clear that contact will be established, but the exact positioning of multiple bodies is difficult during modeling. They are not meant to simulate general rigid body dynamics; nor are they meant for contact chattering situations or to resolve initially tight clearances between mating surfaces (see “Modifying contact controls to help solve difficult contact simulations” later in this section for this purpose).

When either form of automatic stabilization is used, ABAQUS/Standard activates viscous damping for relative motions of the contact pair at all slave nodes, in the same manner as contact damping (see “Contact damping,” Section 22.1.3). The stabilization works only for the step in which it is specified; in subsequent steps the stabilization is removed, even if contact was not established or if rigid body motions appear later because of complete separation of the contact pair. If needed, you should specify stabilization for subsequent steps as well.

There are some important differences between the two stabilization methods.

This method is meant specifically to address situations where a single rigid body mode exists normal to the contact direction. It applies damping only in the contact direction to a specific contact pair that you select and calculates the damping coefficient automatically such that contact is established in the first part of the step. The first increment of a step that has this form of stabilization activated will always produce at least two attempts: ABAQUS uses the first attempt to calculate the damping coefficient.

In the first half of the step the viscous damping is maintained at a constant value, and in the second half of the step it is decreased linearly to zero. If no stabilization is applied in the next step, the solution is continuous since the viscous forces at the end of the previous step are already zero. Care should be exercised in cases that require a restart analysis to be run from the middle of a step in which this form of stabilization is used. If the original step is terminated before restart (see “Truncating a step” in “Restarting an analysis,” Section 7.1.1), convergence difficulties may occur because viscous forces will then be removed abruptly. Contact controls should be activated in a continuation step of this kind.

Usually, stabilization based on the initial opening distance is used only in the first step of an analysis. However, it can be used in an analysis step subsequent to the first for the purpose of establishing contact between separated bodies that do not have rigid body motions initially. During the step in which this form of stabilization is activated, the applied loading should be restricted to that necessary to establish contact, and additional deformation of the bodies during the step should not be significant.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT CONTROLS, APPROACH, MASTER=master surface, SLAVE=slave surface |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Stabilization based on the initial opening distance is not supported in ABAQUS/CAE. Use the more general stabilization based on the stiffness of the underlying elements (described below) instead. |

This method is meant to address more general situations. By default, the damping coefficient is calculated automatically at each slave node based on the stiffness of the underlying elements and the step time, is applied to all contact pairs equally in the normal and tangential directions, is ramped down linearly over the step, and is active only when the distance between the contact surfaces is smaller than a characteristic surface dimension.

Although the automatically calculated damping coefficient will typically provide enough damping to eliminate the rigid body modes without having a major effect on the solution, there is no guarantee that the value is optimal or even suitable. This is particularly true for thin shell models, in which the damping may be too high. Hence, you may have to increase the damping if the convergence behavior is problematic or decrease the damping if it distorts the solution. The first case is obvious, but the latter case requires a post-analysis check. There are several ways to carry out such checks. The simplest method is to consider the ratio between the energy dissipated by viscous damping and a more general energy measure for the model, such as the elastic strain energy. These quantities can be obtained as output variables ALLSD and ALLSE, respectively. More detailed information can be obtained by comparing the contact damping stresses CDSTRESS (with the individual components CDPRESS, CDSHEAR1, and CDSHEAR2) to the true contact stresses CSTRESS (with the individual components CPRESS, CSHEAR1, and CSHEAR2). If the contact damping stresses are too high, you should decrease the damping. The comparison should be made after contact is firmly established; the contact damping stresses will always be relatively high when contact is not yet or only partially established.

The easiest way to increase or decrease the amount of damping is to specify a factor by which the automatically calculated damping coefficient will be multiplied. Typically, you should initially consider changing the default damping by (at least) an order of magnitude; if that addresses the problem sufficiently, you can do some subsequent fine-tuning. In some cases a larger or smaller factor may be needed; this is not a problem as long as a converged solution is obtained and the dissipated energy and contact damping stresses are sufficiently small.

It is also possible to specify the damping coefficient directly. This is particularly useful if ABAQUS is not able to calculate a sensible damping value. For example, this may be the case if the slave surface is a node-based surface, in which case the properties of the underlying elements are not available. Direct specification of the damping value is not easy and may require some trial and error. For efficiency reasons this may best be done on a similar model of reduced size. If the damping coefficient is specified directly, any multiplication factor specified for the default damping coefficient is ignored.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to use the default damping coefficient: |

*CONTACT CONTROLS, STABILIZE Use the following option to specify a scale factor for the default damping coefficient: *CONTACT CONTROLS, STABILIZE=factor Use the following option to specify the damping coefficient directly: *CONTACT CONTROLS, STABILIZE damping coefficient |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Stabilization: Automatic stabilization, Factor: factor or Stabilization coefficient: damping coefficient |

You can specify the ramp-down factor at the end of the step. By default, this value is equal to zero, so that the damping vanishes completely at the end of the step. Entering a nonzero value for this factor can be useful in cases where the rigid body modes are not fully constrained at the end of the step; for example, if the problem is frictionless and sliding motions can occur but there is no net force in the sliding direction. In that case it is usually desirable to maintain the small damping in the next step by using the value used for the ramp-down as the multiplication factor for the damping coefficient. If needed, you can maintain this damping level by setting the ramp-down factor equal to one.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to specify a ramp-down factor at the end of the step: |

*CONTACT CONTROLS, STABILIZE , ramp-down factor |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Stabilization: Automatic stabilization or Stabilization coefficient, Fraction of damping at end of step: ramp-down factor |

By default, the opening distance over which the damping is applied (the damping range) is equal to the characteristic slave surface facet dimension; if such a dimension is not available (for example, in the case of a node-based surface), a characteristic element length obtained for the whole model is used. The damping is 100% of the reference value for openings less than half the damping range and from there is ramped to zero for an opening equal to the damping range. Alternatively, you can specify the damping range directly, overriding the calculated value. This can be useful if the damping should work only for a narrow gap, or if the damping should be in effect regardless of the opening distance. In the latter case a large value should be entered.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to specify the damping range directly: |

*CONTACT CONTROLS, STABILIZE , , damping range |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Stabilization: Automatic stabilization or Stabilization coefficient, Clearance at which damping becomes zero: Specify: damping range |

By default, the damping in the tangential direction is the same as the damping in the normal direction. However, if a lower or higher value is desired, you can decrease or increase the tangential damping or set it to zero.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to modify the tangential damping: |

*CONTACT CONTROLS, STABILIZE, TANGENT FRACTION=value |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Stabilization: Automatic stabilization or Stabilization coefficient, Tangent fraction: value |

For certain problems it may be desirable to apply stabilization only for certain contact pairs. In that case you can specify the master and slave surfaces to identify the contact pair. The values specified for a contact pair will override the values given for the whole model, if any.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to apply stabilization only to specific contact pairs: |

*CONTACT CONTROLS, STABILIZE=value, MASTER=master surface, SLAVE=slave surface |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | In ABAQUS/CAE contact controls are always applied to a specified contact pair. |

Interaction module: contact interaction editor: Contact controls: contact controls name |

Whenever a node involved in contact is penetrating its master surface, ABAQUS/Standard tries to resolve the overclosure in a single increment. If the overclosure occurs during the simulation and is so severe that a converged solution cannot be obtained, ABAQUS/Standard will cut back on the increment size in an attempt to reduce the magnitude of the overclosure. However, if the overclosure is present at the start of the analysis, cutting back the increment size will not solve the problem. In this case you can prescribe allowable interferences to allow ABAQUS/Standard to resolve the excessive overclosure gradually during the first step of the analysis.

Allowable interferences can be specified for both the surface-based contact capability and for contact elements. However, they cannot be used with self-contact. In the case of small sliding you can specify allowable interferences in conjunction with initial clearances (see “Defining a precise initial clearance or overclosure” in “Adjusting initial surface positions and specifying initial clearances in ABAQUS/Standard contact pairs,” Section 21.2.3) to resolve user-prescribed precise overclosures gradually.

There are three different ways in which to specify the allowable interference ![]() . By default, in all cases the value of the specified allowable interference is applied instantaneously at the start of the step and then ramped down to zero linearly over the step, unless you specify an amplitude reference that defines a particular allowable interference-time variation.

. By default, in all cases the value of the specified allowable interference is applied instantaneously at the start of the step and then ramped down to zero linearly over the step, unless you specify an amplitude reference that defines a particular allowable interference-time variation.

The contact constraint imposed at each slave node is that the current penetration of the node ![]() is

is ![]() . When

. When ![]() is positive, the slave node is penetrating its master surface. The specified allowable interference

is positive, the slave node is penetrating its master surface. The specified allowable interference ![]() modifies the contact constraint as follows:

modifies the contact constraint as follows:

![]()

When the contact interference is specified, the COPEN output variable does not reflect the actual overclosure value during the step; it reflects the actual value only at the end of the step.

You must specify the contact pairs or contact elements at which the allowable interference should apply.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to define an allowable interference for contact pairs: |

*CONTACT INTERFERENCE, TYPE=CONTACT PAIR slave surface, master surface, Use the following option to define an allowable interference for contact elements: *CONTACT INTERFERENCE, TYPE=ELEMENT contact element set, |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: interaction editor: Interference Fit: Gradually remove slave node overclosure during the step, Uniform allowable interference, Magnitude at start of step: |

| Element-based contact is not supported in ABAQUS/CAE. |

You can define a time-varying allowable contact interference by creating an amplitude curve (see “Amplitude curves,” Section 19.1.2, for details) and then referring to this curve from the contact interference definition.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT INTERFERENCE, AMPLITUDE=amplitude_curve_name |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: interaction editor: Interference Fit: Gradually remove slave node overclosure during the step, Uniform allowable interference, Amplitude: amplitude_curve_name |

By default, only the allowable contact interferences defined or redefined by a particular contact interference definition will be modified. Alternatively, you can specify that all previously defined allowable contact interferences should be removed from the model and only those defined with this definition will remain.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to add or modify an allowable contact interference definition: |

*CONTACT INTERFERENCE, OP=MOD Use the following option to remove all previously defined allowable contact interferences: *CONTACT INTERFERENCE, OP=NEW |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Contact interferences in ABAQUS/CAE propagate along with the interaction for which they are defined. You cannot remove all previously defined contact interferences at once in ABAQUS/CAE. |

A single allowable interference ![]() can be specified for every node on the slave surface or every slave node in the specified set of contact elements. The concepts of slave nodes for the various families of contact elements are discussed in their respective sections. The specified allowable contact interferences are included in the current penetrations of the slave nodes reported in the message file when you request detailed contact printout. Thus, any slave node that penetrates the master surface by less than the allowable interference will be reported as being open.

can be specified for every node on the slave surface or every slave node in the specified set of contact elements. The concepts of slave nodes for the various families of contact elements are discussed in their respective sections. The specified allowable contact interferences are included in the current penetrations of the slave nodes reported in the message file when you request detailed contact printout. Thus, any slave node that penetrates the master surface by less than the allowable interference will be reported as being open.

This method is applicable only during the first step of an analysis and requires no interference value. With this method ABAQUS/Standard assigns a different ![]() to each slave node that is equal to that node's initial penetration (or zero if the point is initially open). These automatically calculated allowable contact interferences are not included in the current penetrations of the slave nodes reported in the message file when detailed contact printout is requested.

to each slave node that is equal to that node's initial penetration (or zero if the point is initially open). These automatically calculated allowable contact interferences are not included in the current penetrations of the slave nodes reported in the message file when detailed contact printout is requested.

When the automatic “shrink” fit method is used, only the default amplitude curve, a linear ramp to zero magnitude, can be used.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT INTERFERENCE, SHRINK |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: interaction editor: Interference Fit: Gradually remove slave node overclosure during the step, Automatic shrink fit |

In this method you specify a uniform allowable interference ![]() and a direction

and a direction ![]() . A relative shift

. A relative shift ![]() is applied to the slave nodes before ABAQUS/Standard determines the contact conditions. In certain applications, such as contact simulations of threaded connectors, shifting the surfaces in a specified direction is more effective than simply allowing an interference.

is applied to the slave nodes before ABAQUS/Standard determines the contact conditions. In certain applications, such as contact simulations of threaded connectors, shifting the surfaces in a specified direction is more effective than simply allowing an interference.

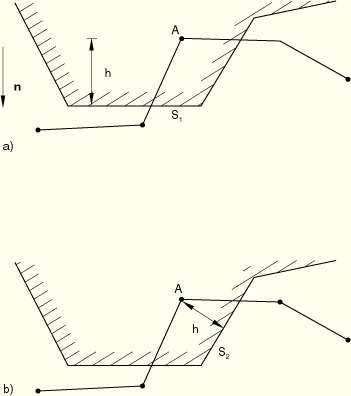

Figure 21.2.9–6 illustrates the potential difference that can result when using an allowable contact interference with a shift vector rather than using a uniform allowable contact interference. In case (a) a shift direction n is defined as well as an allowable interference ![]() , while in case (b) the standard approach is used, with an allowable interference

, while in case (b) the standard approach is used, with an allowable interference ![]() .

.

Figure 21.2.9–6 Effect of direction definition on interference accommodation: a) with direction, b) without direction.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to define an allowable interference with a shift vector: |

*CONTACT INTERFERENCE slave surface, master surface, |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: interaction editor: Interference Fit: Gradually remove slave node overclosure during the step, Uniform allowable interference, Magnitude at start of step: |

Frequently, an actual assembly process is modeled as an interference fit problem. If frictional interface properties are desired, they should usually be introduced after the initial interference has been resolved. The initial interference problem should be modeled under frictionless conditions since the physical assembly process is not typically modeled exactly. Friction can be introduced in subsequent steps (see “Changing friction properties during an ABAQUS/Standard analysis” in “Frictional behavior,” Section 22.1.4).

The standard solution controls for contact simulations work well for the majority of problems. Additional controls can be used for problems where the standard controls do not provide cost-effective solutions. Such problems are generally large models with complicated geometries and numerous contact interfaces.

You can apply contact controls on a step-by-step basis to all of the contact pairs and contact elements that are active in the step or to individual contact pairs. This makes it possible to apply contact controls to a specific contact pair to take the simulation through a difficult phase.

Contact controls remain in effect until they are either changed or reset to their default values. However, when stabilization based on the initial opening distance is used, the stabilizing damping is applied only for the duration of the step in which the controls are specified.

If in any given step the contact controls are declared for both the entire model and for a specific contact pair, the controls for the specific contact pair will override those for the entire model for that contact pair.

You can apply contact controls to any number of specific contact pairs.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT CONTROLS, SLAVE=slave surface, MASTER=master surface contact control options |

| Repeat this option to apply contact controls to several contact pairs. |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: contact interaction editor: Contact controls: contact controls name |

You can reset all contact controls to their default values, or you can remove the controls for a specific contact pair.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to reset all contact controls: |

*CONTACT CONTROLS, RESET Use the following option to remove the controls for a specific contact pair: *CONTACT CONTROLS, SLAVE=slave surface, MASTER=master surface, RESET |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: contact interaction editor: Contact controls: (Default) |

| You cannot reset all contact controls at once in ABAQUS/CAE. |

These controls allow you to specify that nodes on the contact interfaces can violate “hard” contact conditions. In addition, these controls can be used to modify the behavior of the augmented Lagrangian contact constraint enforcement. The “softened” and the no separation pressure-overclosure relationships cannot be modified by the contact controls.

A node can violate the contact condition in one of two ways. First, ABAQUS/Standard may consider that there is no contact at that node, even though the node has penetrated the master surface by a small distance. Second, ABAQUS/Standard may consider that there is contact at a node, even though the normal pressure transmitted between the contacting surfaces at the node is negative (that is, a tensile stress is being transmitted).

ABAQUS/Standard can calculate tolerances for separation and penetration automatically by calculating acceptable small separation forces or penetration distances as compared to the global solution. Alternatively, you can specify the maximum allowable overclosure and tensile contact pressure tolerances. Furthermore, you can limit the number of nodes at which these tolerances can be exceeded. The contact status will change for nodes in excess of the specified limit when violating these tolerances.

You can have ABAQUS/Standard automatically calculate separation and penetration tolerances. These tolerances are derived from the convergence tolerances currently active in the problem (see “Convergence criteria for nonlinear problems,” Section 8.3.3).

The automatic penetration tolerance is equal to twice the largest allowable displacement correction. The automatic separation tolerance, when multiplied by the area associated with the contact point, is set to ten times the largest allowable residual during the first two iterations and is set to the largest allowable residual during any subsequent iteration. If convergence should occur in the first two iterations with these automatic tolerances, at least one more additional iteration is made, with the separation tolerance equal to the largest allowable residual. The objective of these automatic tolerances is to help with problems that exhibit contact chatter and normally require several iterations just to determine which nodes are in contact and which nodes are open.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT CONTROLS, AUTOMATIC TOLERANCES |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: toggle on Automatic overclosure tolerances |

You can specify the maximum allowable penetration distance, ![]() , that ABAQUS/Standard will accept without changing the contact status. If the penetration is larger than

, that ABAQUS/Standard will accept without changing the contact status. If the penetration is larger than ![]() , the contact status will change, causing another iteration. You must also specify the maximum number of nodes, n, that are permitted to violate the default contact conditions in any increment. If more than n nodes violate the default contact conditions, the contact status will change, which will cause another iteration.

, the contact status will change, causing another iteration. You must also specify the maximum number of nodes, n, that are permitted to violate the default contact conditions in any increment. If more than n nodes violate the default contact conditions, the contact status will change, which will cause another iteration.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT CONTROLS, UERRMX= |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Max number of points that can violate contact: |

You can specify the maximum allowable tensile contact pressure, ![]() , that ABAQUS/Standard will accept without changing the contact status. If the tensile contact pressure is larger than

, that ABAQUS/Standard will accept without changing the contact status. If the tensile contact pressure is larger than ![]() , the contact status will change, causing another iteration. You must also specify the maximum number of nodes, n, that are permitted to violate the default contact conditions in any increment. If more than n nodes violate the default contact conditions, the contact status will change, which will cause another iteration.

, the contact status will change, causing another iteration. You must also specify the maximum number of nodes, n, that are permitted to violate the default contact conditions in any increment. If more than n nodes violate the default contact conditions, the contact status will change, which will cause another iteration.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT CONTROLS, PERRMX= |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Max number of points that can violate contact: |

For augmented Lagrange contact you can specify the allowable penetration that is permitted to violate the impenetrability condition. Alternatively, you can specify the ratio of the allowable penetration to the characteristic contact surface dimension. In addition, you can modify the default penalty stiffnesses calculated by ABAQUS/Standard by specifying a factor by which to scale the defaults. Choosing a small penetration tolerance or a high penalty stiffness may result in an excessive number of iterations or convergence difficulties.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT CONTROLS, ABSOLUTE PENETRATION TOLERANCE=tolerance, RELATIVE PENETRATION TOLERANCE=tolerance, STIFFNESS SCALE FACTOR=factor |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Stiffness scale factor: factor, Penetration tolerance: Absolute: tolerance or Relative: tolerance |

By default, tangential contact constraints are applied as soon as contact is established. In most cases, this will yield satisfactory results and reasonable convergence. However, experience has shown that applying the normal constraint in the increment when contact is established and applying the tangential constraints in the subsequent increment can sometimes lead to improved convergence, particularly if frictional stresses have a strong effect on contact stresses.

In such cases you can change the default behavior to delay friction to the increments subsequent to the increment in which a contact point closes. This is not recommended if the contact zone changes rapidly as the analysis progresses; in that case, the absence of friction immediately after closure can lead to rapid, nonphysical oscillations in the frictional forces. This setting applies for all kinds of friction, including rough friction; but it has no effect on user subroutine FRIC, which is called whenever contact occurs at the end of an increment. You can restore the default behavior as needed.

| Input File Usage: | Use the following option to delay friction: |

*CONTACT CONTROLS, FRICTION ONSET=DELAYED Use the following option to restore the default behavior: *CONTACT CONTROLS, FRICTION ONSET=IMMEDIATE |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: Friction onset: Delayed or Immediate |

In finite-sliding simulations a slave node may come into contact with any of the elements underlying the master surface. If the equation system is not allowed to change, an association has to be made between the slave node and all the master surface nodes, which may result in a large wavefront. This problem is compounded for three-dimensional deformable master surfaces with a large number of underlying elements. This may result in a wavefront so large that there is insufficient memory to solve the finite element equilibrium equations.

ABAQUS/Standard employs an automated contact patch algorithm to reduce the wavefront and solution time for two-dimensional and three-dimensional finite-sliding analysis for both deformable-to-deformable and deformable-to-rigid contact. The wavefront can be reduced significantly if each slave node is limited to an allowable area of contact, defined as a contact patch, during a given period of time. When a slave node slides off its contact patch, a new association between the slave node and the elements underlying the master surface in the immediate neighborhood has to be made. A new contact patch is defined, the elements are reordered to optimize the wavefront, and the analysis is continued.

Figure 21.2.9–7 illustrates the concept of the contact patch for three-dimensional deformable-to-deformable contact simulations.

The point on the master surface closest to each slave node is computed for the current geometry. The closest point is then used as the center of the sphere of radius R (maximum slide distance), as shown in Figure 21.2.9–7 for slave nodes 2 and 7. Any facet of the master surface that has at least one node inside this sphere will be part of the allowable area of contact for the slave node. For example, the allowable area of contact for slave node 2 in Figure 21.2.9–7 consists of facets 1, 2, 3, 11, 12, and 13; and the allowable area of contact for node 7 consists of facets 4 and 14.By default, ABAQUS/Standard will select and adjust the contact patch size and position to reduce the analysis time. The initial patch size is selected as a small multiple of the master surface characteristic facet length.

ABAQUS/Standard monitors the relative displacement increment size of each slave node. If the relative displacement increment is small compared to the contact patch, the contact patch may be reduced in size to obtain a more optimal wavefront. If the relative displacement increment is large compared to the contact patch, the patch size is increased to avoid frequent redefinition of contact patches and element reordering.

You can overwrite the patch size calculated by ABAQUS/Standard by specifying the maximum slide distance for finite-sliding simulations with three-dimensional deformable master surfaces. In this case the maximum slide distance and patch location will remain fixed until the maximum slide distance is respecified. Specifying a maximum slide distance can be effective in reducing the wavefront if the relative motion of the slave and master surfaces is limited, such as may typically arise in “structural” contact problems and in cases of master surfaces with very few underlying elements where the whole surface should be included. The maximum slide distance must be applied to a particular contact pair.

When a maximum slide distance is respecified for a contact pair, a new patch of the specified size is created around the point of contact at the beginning of the step. This is true even if the specified value of the slide distance remains the same. If a slide distance of zero is specified, the default (automatic) algorithm will be used from that point forward.

If a slave node slips off its allowable area of contact, ABAQUS/Standard will issue a warning message and force a cutback. If the cutbacks cause ABAQUS/Standard to terminate the analysis, the problem may be restarted. In such a case you must end the analysis at the time of restart (see “Truncating a step” in “Restarting an analysis,” Section 7.1.1) and specify a different patch size to force ABAQUS/Standard to redefine the contact patches at the start of the restart analysis.

| Input File Usage: | *CONTACT CONTROLS, SLIDE DISTANCE=maximum slide distance, MASTER=master surface, SLAVE=slave surface |

| ABAQUS/CAE Usage: | Interaction module: ABAQUS/Standard contact controls editor: toggle on Specify slide distance: maximum slide distance |