Pi Car Comm

Proposal

Overview

The goal of this project is to establish vehicular communication between a group of PiCars. The end goal is to demonstrate this capability, specifically as it applies to collision avoidance between two or more vehicles.

Members

- Patrick Naughton

- Yak Fishman

- Jacob Cytron

- TA: Sam Hoff

- Instructor: Proffesor Mell

Objectives

- Establish an ad hoc network between many (potentially up to 10, at least 2) Pi Cars

- Use this communication capability to avoid collisions in a demonstration involving at least 2 Pi Cars

Challenges

Data Transfer Rate

As the cars will be moving quickly, one of the main challenges will be ensuring that each car can establish and modify its network extremely quickly. Thus, not just data transfer, but also network establishment speed will be important.

Additionally, simultaneously addressing all valid addresses will be difficult to do efficiently.

Security

Since we're using Wi-Fi, there is a potential for a malicious actor to transmit faulty messages that could trick a car.

Fortunately, since the Pi's and/or cars will not be connected to the Internet, a malicious actor would have to be physically close to the car (within the range of the Wi-Fi), substantially limiting the number of potential attackers.

Hardware

As the project progressed, it became clear that interacting with the hardware of the PiCars was going to be a large challenge. First, the Raspberry Pi itself cannot source or sink enough current to drive the steering servo and its native PWM capabilities are not capable of reliably signaling the ESC for the drive motor. These two problems required that the Pi communicate with an on board Arduino to drive the car's two motors. Additionally, power supplies on the cars were quite unreliable. Some cars ran off of 7.4 V batteries, while others required 11.1 V. Furthermore, sometimes batteries were completely unavailable which frustrated efforts to test the cars and demo multiple times. The voltage disparity also caused one motor to drive much faster than the other.

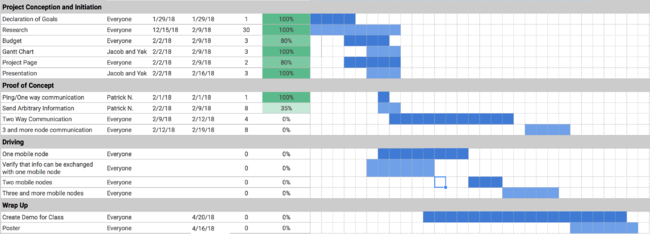

Gantt Chart and Presentation

Budget

Design & Solutions

Establishing a network

The WiFi protocol was used to communicate between cars. In order to use this protocol, the cars must establish a network over which to broadcast their messages. For this project, an ad-hoc mesh network was chosen as an appropriate configuration for two main reasons. First, it is distributed meaning that no car depends on any others being connected to the network to use it. If a given car doesn't find the network it's trying to join, it simply creates it. Second, it is adaptive. Because of the nature of driving cars, the topology of any network connecting them is subject to rapid change as they move in and out of range of each other. A mesh network can easily handle this changing structure (unlike the more static networks traditionally used to connect devices to the Internet). Each Pi Car was modified such that they would either try to join a network called "bakery" on startup or, failing that, would create such a network. This meant that as soon as a car booted up, it would be connected to all of the other cars in its vicinity.

Sending data over the network

Because the information being sent between cars was relatively simple (it can be represented as a string of bytes), sockets were used as the network interface. Each car initiated a process to listen on a socket for any messages being broadcast and created a different socket for sending messages of its own. To send a message of its own, the cars could simply send a packet of bytes to the network broadcast address, "255.255.255.255" and any cars that were listening would receive it.

As the topology of the network could change rapidly, the cars send UDP packets because UDP is connectionless (cars don't need to perform a handshake with one specific other car to send data to them). This allows cars to "fire and forget" packets across the network. Dropped packets are not that large of a concern because cars rebroadcast their status every few milliseconds, so one dropped data point will not make that large of a difference.

Intra-car communication

The Raspberry Pi often has difficulty sending PWM signals, and therefore was not a suitable board to control the physical elements of the car, namely the steering servo and ESC. Because of this, an Arduino Uno was used to interface between these hardware components and the Pi. The two boards communicated over serial. This solution was effective but slow. In the future, using a SPI bus for communication would likely allow the car to respond more quickly to commands from the Pi.

Resources

An Instructable on how to build a Pi Car can be found here. It includes parts needed- both 3d printed parts and parts ordered, as well as a step by step guide to putting the car together.

Our GitHub with all code used in this project. Documentation is expanded upon here.

Here are two tutorials on Creating an Ad Hoc Network on the Raspberry Pi and Socket Programming.

Our UML can be found below

The software of the project was designed to be easily integrated into any future project. To include network functionality in a new project, one simply has to from core.network import Network and then construct a network object: network = Network(1024, 10). To allow one network object to both listen for and broadcast packets, if the user calls network.start_listening(), the program will create a separate process (similar to a second thread) that will report back any messages it hears. This combined functionality simplifies and reduces the amount of code necessary to integrate this project's functionality in future endeavors. Further documentation and more examples can be found on our GitHub.

Results

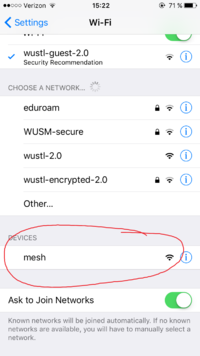

We were able to achieve our baseline goal of establishing an ad network of communication between Pi Cars. As shown in the picture below the Pis were able to create an ad-hoc network.

They are able to send information (up to 4 KB) to and from each other just as we hoped. Below is two pictures of one Pi sending a series of texts and a different Pi receiving the messages and displaying them proving our network works.

We were ultimately able to establish a network and send packets quite quickly. To test the network, a PiCar was mounted on a mobile base which was drive past a stationary Pi. The stationary Pi simply compared the timestamps of incoming messages with the current time to figure out the time of flight of the messages. A video of the experiment and a file containing its results are displayed below. Messages consistently spent less than a tenth of a second between cars which, given the scale and speed at which the cars operate, can be considered almost instantaneous.

Mobile Test Results Mobile Timing Movie

Our biggest limiting factor was the hardware, and ultimately led us to make critical decisions about our demo. Below is a picture of the main car we were using

The batteries on the cars weren't always so reliable, and in fact, one of them became too discharged and unusable during our demo. Most of the cars we were using were not identical and the motors of the two cars we were using were vastly different. Because of this, our originally planned demo of having several cars driving around each other without colliding was not feasible.

Though we weren't able to have one car follow another car, we have the code and network set up to allow that. We were able to implement a demo in which we drove two cars around and those cars sent information to a stationary Raspberry Pi. The cars were sending values representing how much throttle they had and how much they were steering. If the cars were identical, then they could use this sent information to mimic each other. But because the motors were different, an increase in the throttle of one Pi Car has a much different effect than on the other. Instead, we had the stationary Raspberry Pi hooked up to a computer and displaying all the different values that both cars were sending. Unfortunately by the time of the demo, the battery of the second car had died and so only one car could actually be driven during the final demonstration.

If we could do this project over again, we would build our own Pi Cars, with uniformity in hardware being a higher priority. We would also look into a more reliable power source.

A link to our final poster has been added below

Future Work

The most obvious way this project could be improved would be to create some sort of GPS that could give the cars a sense of their global position. This would allow us to close the loop of the car-following-another-car demo because the lead car could broadcast its position instead of its control outputs and the following car could try to get to that position, rather than simply try to mimic the first car's control outputs. Additionally, a way for the cars to find their global position would allow them to know if they were on a collision course and negotiate trajectories for each of them to follow to minimize the chance that a collision actually occurs.