Bash

Bash is the default shell environment in Linux; that is, it is the interface in which you will be interacting with your Linux server. Bash is a derivative of sh, one of the first shells. Other popular shells include csh and tcsh, shells with c-like syntax for scripting, and zsh a bash-like shell which focuses on extending the capabilities of the shell environment.

Displaying a Value

To display a value at the shell prompt, use the command echo.

$ echo "Hello World" # displays Hello World

Hello World

$

Note: In examples, code written at the prompt is conventionally denoted by a line starting with a currency symbol. Lines without a currency symbol represent output.

Seeing the contents of a file

If you want to see the contents of a file, use the cat command.

$ cat myfile.txt

Hello World

$

cat is one of a number of useful Linux command-line binaries, the rest of which we will see later.

Working Directory

Whenever you are interacting with the shell, you will be executing commands from a working directory. To see the current working directory, run the command pwd (path to working directory). To change the working directory, run the command cd (change directory).

$ pwd

/home/todd

$ cd projects

$ pwd

/home/todd/projects

$ cd ./ # recall that . is the current directory

$ pwd

/home/todd/projects

$ cd ../ # recall that .. is the next directory up in the filesystem

$ pwd

/home/todd

$

If you run commands that interact with the filesystem (e.g. ones that create or edit files), they will be saved in your current working directory.

Variables

Bash supports the use of variables. There are system-defined variables, and you can also define your own custom variables.

Defining and Accessing Variables

$ MYVARIABLE="Hello World" # assigns the value Hello World to the variable MYVARIABLE

$ echo $MYVARIABLE # notice that you need to put a currency symbol in front of the variable in order to access its value

Hello World

$ export $MYVARIABLE # allows MYVARIABLE to be accessed in child processes (e.g., in a program you call from the shell)

$ export MYVARIABLE="Hello Moon" # a shortcut for defining a variable and exporting it to subprocesses

$ set # displays a list of all currently set variables

MYVARIABLE=Hello World

$

System Variables

Bash comes pre-loaded with certain environment variables. Some of the variables with which you may find yourself interacting include:

- PATH: search path for the commands

- PWD: name of the current directory

- SHELL: type of shell

- TERM: type of the terminal

- USER: the account name

- HOME: the user's home directory

- PS1: the prompt at command line

- $$: the process id of current shell

- $RANDOM: a random value

- $?: the return value of the last command

- $_: the last argument of the previous command

- $#: where # is a number, the value of the #th argument

- IFS: input field separator

Try echoing some of the system variables to examine your current environment.

Running Programs

To run an executable file, simply enter its filename into the shell prompt:

$ /usr/bin/perl -v # runs the binary executable located at /usr/bin/perl with the flag -v

This is perl 5, version 12, subversion 3 (v5.12.3)

$ ../mydir/myprogram # runs the binary located one level up in the file system, then in mydir/myprogram

You just ran myprogram!

$

Programs in your PATH

Many commonly-used executable binaries are located in /bin, /usr/bin, and similar directories. In order to avoid typing paths to these directories every time you want to execute a command, you define these directories in your PATH system variable:

$ echo $PATH # displays the current value of the PATH variable

/opt/local/bin:/opt/local/sbin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/usr/local/bin

$ PATH=$PATH:/my/favorite/bin # adds a directory to your PATH variable

$ echo $PATH

/opt/local/bin:/opt/local/sbin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/my/favorite/bin

$

Notice that the different PATH directories are separated by colons. Now, when you execute a command, Bash will scan all of the directories in your PATH variable. To see the path to the binary that Bash found, use the which command.

$ perl -v

This is perl 5, version 12, subversion 3 (v5.12.3)

$ which perl

/usr/bin/perl

$

Note: it is unwise to have . in your PATH. Instead, if you want to run an executable in the current directory, do so by calling ./myprogram:

$ ./myprogram

You just ran myprogram!

$ myprogram

-bash: myprogram: command not found

$

Foreground and Background Processes

A program runs in the foreground (unless it detaches itself from the terminal) by default. You can run a program in the background by adding & at the end of the command (after arguments). In this case, the shell would fork a process for that program and enable the command prompt back for input. At any time, jobs command can be used to see the processes running at the background. fg command brings the specified process back to foreground. A program running in the foreground can be stopped by typing ctrl-c in most cases. Typing ctrl-z interrupts a program running in the foreground. If a program is interrupted, it will not continue executing until it is resumed. An interrupted program can be brought back to foreground by fg, or it could be send to background by bg.

$ ./myprogram

You just ran myprogram!

I am taking a long time to run.

^C

$ jobs

$ ./myprogram

You just ran myprogram!

I am taking a long time to run.

^Z

[1]+ Stopped ./myprogram

$ jobs

[1]+ Stopped ./myprogram

$ bg

[1]+ ./myprogram &

$ jobs

[1]+ Running ./myprogram &

$ fg

^C

$ jobs

$ ./myprogram &

[1] 64741

$ jobs

[1]+ Running ./myprogram &

$

Killing Processes

A process can be killed by using the kill command: kill process-number

In some cases the kill signal can be ignored, so it may be necessary to force kill the program by sending an absolute KILL signal: kill -9 process-number

The current processes can be listed using the ps command.

$ ps # list currently running processes in the current shell

PID TTY TIME CMD

19107 ttys000 0:00.75 -bash

1873 ttys001 0:00.05 -bash

57267 ttys002 0:00.20 -bash

50721 ttys003 0:00.55 -bash

$ ps -eaf # list all currently running processes

UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD

0 1 0 0 31Dec00 ?? 3:24.45 /sbin/launchd

0 19106 327 0 1Aug12 ttys000 0:00.03 login -pfl sffc /bin/bash -c exec -la bash /bin/bash

501 19107 19106 0 1Aug12 ttys000 0:00.75 -bash

0 1872 327 0 31Jul12 ttys001 0:00.02 login -pfl sffc /bin/bash -c exec -la bash /bin/bash

501 1873 1872 0 31Jul12 ttys001 0:00.05 -bash

0 57266 327 0 Mon05AM ttys002 0:00.08 login -pfl sffc /bin/bash -c exec -la bash /bin/bash

501 57267 57266 0 Mon05AM ttys002 0:00.20 -bash

0 64747 57267 0 9:58AM ttys002 0:00.00 ps -eaf

0 50720 327 0 Fri12AM ttys003 0:00.03 login -pfl sffc /bin/bash -c exec -la bash /bin/bash

501 50721 50720 0 Fri12AM ttys003 0:00.55 -bash

$

Directing Output

A program's standard output can be send to a file by typing >filename at the end. Similarly, >> appends to a file. In Linux, there are three default file handlers, standard input or STDIN, standard output or STDOUT, and standard error or STDERR. STDOUT has a file handler number 1 and STDERR has a number of 2. In bash, you can direct either of these handlers to a file. You can also redirect one file handler to another.

$ ./myprogram >filename.txt # redirects all output to filename.txt

$ cat filename.txt

You just ran myprogram!

$ ./myprogram >>filename.txt # appends the output to filename.txt

$ cat filename.txt

You just ran myprogram!

You just ran myprogram!

$ ./myprogram 1>filename.txt # redirects the standard output to filename.txt

$ cat filename.txt

You just ran myprogram!

$ ./myprogram 2>filename.txt #redirects the error output to filename.txt

You just ran myprogram!

$ ./myprogram 2>&1 # STDERR is redirected to STDOUT

You just ran myprogram!

$

Output of one program can be redirected to the input of another program using pipes.

$ ./program1 | ./program2 # send program1's output as an input to program2

You just ran program2 with the input: You just ran program1!

$

Redirection is possible for STDIN too. A program can get its input by redirecting STDIN using <

$ ./myprogram < inputfile.txt

You just ran myprogram with input from inputfile.txt!

$

Finally, ` (a backtick) can be used to capture the output of a program, and use it as a string such as in setting a variable

$ MYVARIABLE=`./myprogram`

$ echo $MYVARIABLE

You just ran myprogram!

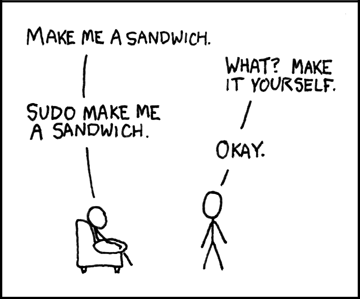

SUDO

Some commands require root privileges to run. In order to run a command as root without logging in as root, use sudo.

$ yum install lynx

You need to be root to perform this command.

$ sudo yum install lynx

[sudo] password:

.....

Complete!

$

Automatically Running Programs

You will often find it useful for binaries to be executed at predefined intervals, certain days of the week, or at startup. Linux provides you with the tools you need to make these configurations.

Scheduled Programs in Cron

Cron is a system service that will run programs in a periodic manner. For more details on how to configure cron, see the Cron guide.

Programs at Startup

When a Linux system boots there are a series of scripts that are called to start up system processes, daemons, and other programs (such as SSH servers, web servers, database programs, etc). The simplest way to add something to the boot process is to add it to /etc/rc.local, which is a script that is called automatically at the very end of the boot process. Simply write a script that does what you want and then call it from with in /etc/rc.local to ensure that your script is called at the end of the boot process.

You can also add scripts which run at different times during the boot process. The way to do this varies by Linux distribution. For Fedora, see http://www.yolinux.com/TUTORIALS/LinuxTutorialInitProcess.html (specifically the section entitled Init Script Activation).

Shell Scripting

Note: This section, Shell Scripting, will not be on any quizzes or assignments in CSE 330, but it is very useful for automating tasks in Linux and even OS X.

As bash is nothing but a command interpreter, it actually comes with a built-in programming language. Users can take advantage of this powerful language to simplify and automate various tasks. Programs written in shell languages (and other interpreted languages) are referred to as scripts. They can be run from the command line like any other program using the correct shell program as the interpreter. The scripts themselves are just text files with lists of commands. For example,

$ bash commandfile

You just ran commandfile!

$

reads and executes the commands from the text file named commandfile. A better approach is to make commandfile executable and run it as if it were a compiled program. For this to work, you must also specify the interpreter of commandfile on the first line of the script file, starting with #! (pronounced sha-bang).

$ cat commandfile

#!/bin/bash

echo "You just ran $0!"

$ chmod a+x commandfile

$ ./commandfile

You just ran commandfile!

$

Statements

Any line in a bash script is a program to be executed. Lines are broken with ;

Conditional statements

Bash supports if statements. The format is

if [ CONDITION ]

then

somecommand

fi

or

if [ CONDITION ]

then

somecommand

else

someothercommand

fi

CONDITION could be a logical statement or it could be a test (run man test for more details). For example

if [ $val = 5 ]

or

if [ $val -eq 5 ]; then

echo value is 5

fi

if [ somefile1 -ot somefile2 ]; then

echo somefile1 is older than somefile2

fi

Bash also has case statements. The format is

case $mywar in

value1)

commands;

;;

value2)

commands;

;;

*)

commands;

;;

esac

In this case, ;; means end of a case block and * means catch anything.

In general, you will nearly always put string variables in quotes, ". To see why, remember that shell variables are simply expanded to their content when used. For example,

myvar="Some very good text was here. Now it is gone and all that is left is this boring message"

if [ $myvar = "This is very good text" ]

would fail with an error message as $myvar would be expanded to its content, like this:

if [ Some very good text was here. Now it is gone and all that is left is this boring message = "This is very good text" ]

To avoid this, you should have the statement as

if [ "$myvar" = "This is very good text" ]

Loop Statements

Bash provides standard loop statements, for, while, until. They can be executed in a script or it could be typed at the command prompt.

The format of for statement is

for VAR in somevalue1 somevalue2 .... somevaluen

do

executesomecommand

done

This loop will execute the for block for each value of VAR. For example,

sum=0

for i in 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

do

sum=$[$sum+$i]

done

would sum numbers from 1 to 10. We can also use other techniques in for line, e.g. replacing for in the above code with

for i in `seq 1 1000`

would get the sum from 1 to 1000. Note the usage of `

The format of while and until are very similar

while [ CONDITION ]

do

execute some command

done

until [ CONDITION ]

do

execute some command

done

For both of these commands, CONDITION is the same as for the if statement.

Functions

Bash also provides functions. They could be defined at the command prompt and then can be called from command prompt. The structure of a function is similar to most modern languages.

myfunction(){

execute some commands

}

The function can then be called with:

myfunction

You can send parameters to the function by adding them next to the function name:

myfunction arg1 arg2 ....

Within a function, you can access the arguments using $#, i.e., $1 for first argument, $2 for second argument, etc.