Product: ABAQUS/Standard

This section describes the constitutive theory for Types 304 and 316 stainless steel in ABAQUS/Standard, as set forth in nuclear standard NE F9–5T(1981). The constitutive theory is uncoupled into a rate-independent plasticity response and a rate-dependent creep response, each of which is governed by a separate constitutive law.

The plasticity theory uses a Mises yield surface that can expand isotropically and translate kinematically in stress space. Nuclear standard NE F9–5T provides for some coupling between the plasticity and creep responses by allowing prior creep strain to expand and translate the subsequent yield surface in stress space. For Types 304 and 316 stainless steel, however, prior plasticity does not change the subsequent creep response.

A set of auxiliary creep and load reversal detection rules, using modified strain hardening creep theory, overcomes the inconsistencies usually encountered with standard strain hardening theories under a stress reversal. In particular, creep theories based on strain hardening assumptions predict creep rates that are too small under conditions of stress reversal, so that the amount of creep that occurs under cyclic loading conditions will generally be underestimated.

The plasticity theory for stainless steels, as set forth in nuclear standard NE F9–5T, employs a von-Mises yield surface with kinematic hardening. Ziegler's hardening rule, generalized to the nonisothermal case, is used in ABAQUS.

Normally, when combined isotropic and kinematic hardening is considered, the center of the yield surface is assumed to translate linearly with plastic strain according to a Prager or Ziegler kinematic hardening rule. Incorporation of isotropic hardening into the constitutive formulation then changes the form of the stress-strain relation but leaves the Prager or Ziegler kinematic shift rule for determining the motion of the center of the yield surface intact. In the ORNL plasticity formulation the form of the stress-strain law is left intact (a bilinear representation in one dimension), and modifications to the kinematic shift rule are made to accommodate isotropic hardening.

The Mises yield surface is used:

where![]()

![]()

The model uses associated plastic flow, which means that the plastic strain rate is defined by

where![]()

![]()

![]()

For continued satisfaction of the yield condition (Equation 4.3.8–1) during active plastic straining, the consistency condition is

For the evolution of ![]() we use the modified form of Ziegler's hardening rule,

we use the modified form of Ziegler's hardening rule,

The second term in this equation accounts for isotropic hardening, so when this equation is combined with the consistency condition (Equation 4.3.8–3), the terms containing ![]() cancel. This produces a uniaxial stress-strain relation that is bilinear.

cancel. This produces a uniaxial stress-strain relation that is bilinear.

The strain rate decomposition during active plastic loading is

![]()

We use linear elasticity with temperature-dependent moduli, so

![]()

![]()

![]()

Combining this with the flow rule (Equation 4.3.8–2) allows the incremental stress-strain relation to be written in the form

Introducing the evolution equation for ![]() (Equation 4.3.8–4) into the consistency condition (Equation 4.3.8–3) provides

(Equation 4.3.8–4) into the consistency condition (Equation 4.3.8–3) provides

![]()

Projecting Equation 4.3.8–5 onto ![]() gives

gives

![]()

Combining these two definitions then provides ![]() from the total strain rate and temperature change rate as

from the total strain rate and temperature change rate as

![]()

![]()

![]()

The incremental stress-strain relationship during active plastic deformation is now obtained directly from Equation 4.3.8–5 as

Reduction of Equation 4.3.8–3 and Equation 4.3.8–4 to one dimension, with ![]() at large strain values where

at large strain values where ![]() , shows that

, shows that ![]() is the slope of the plastic portion of the uniaxial stress versus plastic strain relation.

is the slope of the plastic portion of the uniaxial stress versus plastic strain relation.

The incremental stress-strain relation (Equation 4.3.8–6) has the same form as that obtained with pure kinematic hardening. As mentioned previously, this is due to the cancellation of the terms ![]() in the expressions for the evolution of

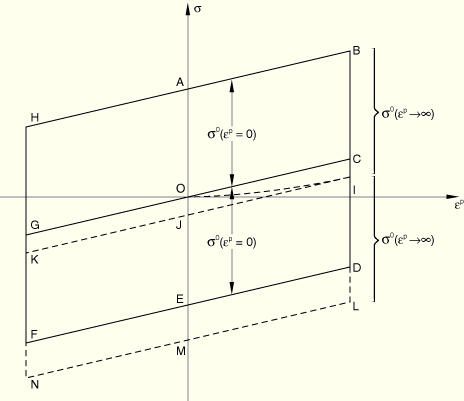

in the expressions for the evolution of ![]() and the consistency relation. The bilinear stress-strain law and the translation of the yield surface center are depicted in Figure 4.3.8–1.

and the consistency relation. The bilinear stress-strain law and the translation of the yield surface center are depicted in Figure 4.3.8–1.

Figure 4.3.8–1 Bilinear stress-strain behavior and movement of the yield surface center with the ORNL plasticity theory.

The yield surface center, thus, follows the path OI under monotonic loading. If point I is sufficiently distant from the origin, point O, so that ![]() at point I, then as

at point I, then as ![]() continues to grow under continued stress reversals, the continued growth of

continues to grow under continued stress reversals, the continued growth of ![]() is governed by pure kinematic hardening, with

is governed by pure kinematic hardening, with ![]() . The yield surface center then translates along the path IJKJI. Unlike pure kinematic hardening the ORNL theory, which allows incremental changes in

. The yield surface center then translates along the path IJKJI. Unlike pure kinematic hardening the ORNL theory, which allows incremental changes in ![]() due to cumulative plastic strain, produces a stress-strain curve that is asymmetric about the stress-strain origin.

due to cumulative plastic strain, produces a stress-strain curve that is asymmetric about the stress-strain origin.

The expansion of the yield surface is approximated by a step change in the value of ![]() . Figure 4.3.8–2 shows the value of

. Figure 4.3.8–2 shows the value of ![]() appropriate to the virgin (initial) stress-strain curve,

appropriate to the virgin (initial) stress-strain curve, ![]() , and the value of

, and the value of ![]() appropriate to the 10th cycle curve,

appropriate to the 10th cycle curve, ![]() .

.

Figure 4.3.8–2 The virgin and 10th cycle ORNL stress-strain curves are assumed to have equal slopes in the plastic portion of the bilinear representation.

These conditions state that a step change in the size of the yield surface occurs when the value of the ORNL equivalent creep strain, ![]() , reaches 0.2% or when yielding first occurs after stress reversal. Nuclear standard NE F9–5T recommends that the yield surface center remain fixed during the step change in

, reaches 0.2% or when yielding first occurs after stress reversal. Nuclear standard NE F9–5T recommends that the yield surface center remain fixed during the step change in ![]() . In this case the term involving

. In this case the term involving ![]() in Equation 4.3.8–6 remains identically equal to zero and the yield surface center translates according to Ziegler's kinematic hardening rule. The nuclear standard recommends that the constant

in Equation 4.3.8–6 remains identically equal to zero and the yield surface center translates according to Ziegler's kinematic hardening rule. The nuclear standard recommends that the constant ![]() in Equation 4.3.8–6 remain fixed on changing the value of

in Equation 4.3.8–6 remain fixed on changing the value of ![]() from the virgin to the 10th cycle values. Since

from the virgin to the 10th cycle values. Since ![]() is the slope of the stress versus plastic strain in a uniaxial tensile test, this implies that the plastic tangent modulus of the 10th cycle stress-strain curve is the same as the plastic tangent modulus of the virgin stress-strain curve. This requirement is also necessary so that the 10th cycle stress-strain curve under fully reversed strain controlled loading is symmetric about the stress-strain origin.

is the slope of the stress versus plastic strain in a uniaxial tensile test, this implies that the plastic tangent modulus of the 10th cycle stress-strain curve is the same as the plastic tangent modulus of the virgin stress-strain curve. This requirement is also necessary so that the 10th cycle stress-strain curve under fully reversed strain controlled loading is symmetric about the stress-strain origin.

The flow rule for ORNL creep theory can be written in the form

where![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The ORNL creep theory now replaces the total effective creep strain, ![]() , in this equation by an effective creep strain,

, in this equation by an effective creep strain, ![]() , determined according to the following algorithm.

, determined according to the following algorithm.

At any time during the creep response the equivalent total creep strain used to define the equivalent creep strain rate is defined as the distance from an origin that is either ![]() or

or ![]() .

. ![]() indicates at any time which origin is active. If the origin is

indicates at any time which origin is active. If the origin is ![]() , we set

, we set ![]() , while if the origin is

, while if the origin is ![]() ,

, ![]() . The quantity

. The quantity ![]() defines the distance in total creep strain space between the current origin and the previous origin. The effective creep strain,

defines the distance in total creep strain space between the current origin and the previous origin. The effective creep strain, ![]() , is then determined by the following steps:

, is then determined by the following steps:

Initially set ![]() set

set ![]() and set

and set ![]() .

.

Set the current origin flag ![]() .

.

Set ![]() .

.

Compute

![]()

![]()

If the current origin is ![]() , the effective creep strain,

, the effective creep strain, ![]() , is decreasing if

, is decreasing if ![]() . Similarly, if the current origin is

. Similarly, if the current origin is ![]() , the effective creep strain,

, the effective creep strain, ![]() , is decreasing if

, is decreasing if ![]() . The rules for choosing a new origin follow in Steps 4 through 14, based on the concept of a decreasing effective creep strain (a load reversal).

. The rules for choosing a new origin follow in Steps 4 through 14, based on the concept of a decreasing effective creep strain (a load reversal).

If ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 5.

and continue to Step 5.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 6.

and continue to Step 6.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 7.

and continue to Step 7.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 8.

and continue to Step 8.

If ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 9.

and continue to Step 9.

If ![]() and

and ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 10.

and continue to Step 10.

If ![]() and

and ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise set ![]() and continue to Step 11.

and continue to Step 11.

If ![]() and

and ![]() and

and ![]() , set

, set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 12.

and continue to Step 12.

If ![]() and

and ![]() and

and ![]() set

set ![]() and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set

and go to Step 13. Otherwise, set ![]() and continue to Step 13.

and continue to Step 13.

If ![]() , go to Step 18. (In this case the load did not reverse during the current creep increment, and no updating of the origins is required.) If

, go to Step 18. (In this case the load did not reverse during the current creep increment, and no updating of the origins is required.) If ![]() or 2, continue to Step 14.

or 2, continue to Step 14.

If ![]() , set

, set ![]() . (In this case the new origin is

. (In this case the new origin is ![]() and the origin flag is set equal to zero.)

and the origin flag is set equal to zero.)

If ![]() , set

, set ![]() . (In this case the new origin is

. (In this case the new origin is ![]() and the origin flag is set equal to one.)

and the origin flag is set equal to one.)

If ![]() , go to Step 18. (In this case the new origin is the same as the current origin. No load reversal has, therefore, taken place; and updating of the origins is not required.)

, go to Step 18. (In this case the new origin is the same as the current origin. No load reversal has, therefore, taken place; and updating of the origins is not required.)

If ![]() , continue to Step 15. (In this case a load reversal has taken place.)

, continue to Step 15. (In this case a load reversal has taken place.)

If ![]() , go to Step 16. (Current origin is

, go to Step 16. (Current origin is ![]() and load reversal has taken place.)

and load reversal has taken place.)

If ![]() , go to Step 17. (Current origin is

, go to Step 17. (Current origin is ![]() and load reversal has taken place.)

and load reversal has taken place.)

If ![]() , leave

, leave ![]() at its current value, set

at its current value, set ![]() , set

, set ![]() , set

, set ![]() , and go to Step 18. (New origin is now

, and go to Step 18. (New origin is now ![]() .)

.)

If ![]() , leave

, leave ![]() , and

, and ![]() at their current values; set

at their current values; set ![]() ; and go to Step 18. (New origin is now

; and go to Step 18. (New origin is now ![]() .)

.)

If ![]() , leave

, leave ![]() at its current value, set

at its current value, set ![]() , set

, set ![]() , set

, set ![]() , and continue to Step 18. (New origin is now

, and continue to Step 18. (New origin is now ![]() .)

.)

If ![]() , leave

, leave ![]() , and

, and ![]() at their current values; set

at their current values; set ![]() ; and continue to Step 18. New origin is now

; and continue to Step 18. New origin is now ![]() .)

.)

If ![]() , set

, set ![]()

If ![]() , set

, set ![]() .

.

Go to Step 1 to determine ![]() for the next creep increment.

for the next creep increment.

![]()