You have been asked to simulate the deep drawing of a can bottom. Analyze this two-stage metal forming process as a quasi-static event, assuming that inertial effects are insignificant compared to stiffness effects. Figure 7–8, Figure 7–9, and Figure 7–10 provide the detailed model description necessary for you to build this model. Since the process is axisymmetric, you can use axisymmetric shell elements to model the blank and axisymmetric rigid surfaces to model the tools. The consequence of using axisymmetric elements instead of the more general three-dimensional shell elements is that an axisymmetric simulation cannot predict wrinkling in the circumferential direction if there are significant circumferential compressive stresses.

Creating the final desired shape of the can bottom requires two separate forming stages. In the first forming stage a thin disk of metal—the blank—is drawn 0.015 m between a punch and a stationary die into the shape of a cup. Once the cup has been formed, the blank is removed from the first set of tools so that it can “spring back” to an unloaded configuration. It is then annealed to relieve the cold-working plastic strains generated during the first forming stage.

After annealing, the blank is placed into a second set of rigid tools, and it is drawn another 0.010 m into the final shape of the bottom of a can. In this forming stage the die, die 2, rests on a spring and dashpot; thus, it is allowed to move in the axial, or 2-, direction. As the punch moves downward, it pinches the blank against die 2 and pushes both the blank and die 2 downward. As the blank moves downward, it contacts the fixed “domer” die, which forms the dome shape in the can bottom. After the second forming stage, the blank is again removed from the tools to spring back to its final, unloaded configuration.

The orientation of the model in the global coordinate system is shown in Figure 7–8 and Figure 7–9. Since the physical process is axisymmetric and is modeled as such, the global 1-, 2-, and 3-directions correspond to radial, axial, and circumferential directions, respectively.

The blank

Since the blank is initially a flat disk, model it with axisymmetric shell elements (SAX1) as a straight line starting at the symmetry axis. The only question, to which there is no definitive answer, is how many elements you should use. Examine the forming processes, and consider the deformations the blank will experience during the analysis. The mesh should be adequate to capture all of the features of the rigid forms accurately.

When using a uniform mesh—as we are in this example—the element size must be small enough to capture the smallest feature of the rigid forms, which is the 0.002 m radius of the punch in forming stage 2. The general rule that we will use is that there should be 10 elements to model that radius, making the maximum element size 0.00125 m. If we use 50 elements in the blank, which is a disk with a radius of 0.045 m, the element length is 0.0009 m, which is adequate. Both dies and punches are composed of straight segments connected by fairly gradual radii. Since there are no sharp bends, there is no need for a terribly fine mesh; no area of the blank is subjected to severe crimping. Assume that 50 elements in the blank is adequate.

The rigid dies and punches

Model the rigid dies and punches with analytical rigid surfaces in forming stage 1 and axisymmetric rigid elements (RAX2) in forming stage 2. An analytical rigid surface provides a smooth representation of the surface as opposed to the piecewise linear representation offered by rigid elements. In this example, it would be straightforward to model the rigid parts in the second forming stage with analytical rigid surfaces. However, most three-dimensional dies and punches require the generality of a rigid surface meshed with rigid elements. In forming stage 2, you must mesh the rigid surfaces finely enough so that they are accurate representations of the actual rigid tools. Mesh each straight segment with a single element, and mesh each radius with 30 rigid elements.

The rigid surfaces should be as close as possible to the blank without any overclosure at the start of the forming step. Remember that ABAQUS/Explicit includes the thickness of shell elements when determining contact; therefore, the midplane of the blank must be at least one-half of the shell thickness away from the rigid tools above and below it. Prior to the first step ABAQUS/Explicit will attempt to resolve overclosures in a strain-free manner, and the resulting nodal location changes may distort the elements. In this example initial overclosures could change the initial shape of the blank if the overclosures are great enough.

Figure 7–11 shows all of the sets necessary to apply the element properties, loads, and boundary conditions, as well as to request output for postprocessing. The sheet metal blank belongs in an element set called BLANK. Create separate node sets for each of the rigid body reference nodes. Give the name REFP1 to the node set containing the reference node for punch 1, and give the name REFD1 to the node set containing the reference node for die 1. Create a node set called BSYM containing the node of the blank that lies on the symmetry axis, and create a node set called BEND containing the node at the free end of the blank.

In addition, create a node set called NHIST containing two nodes for postprocessing. These nodes are selected to provide a detailed velocity history at one point in the bottom flat part and the free end of the blank. Studying the velocity history for typical points in the blank will help to design the loading definition and to debug the analysis. For a mesh of 50 elements, select the 21st node from the symmetry axis and the node at the free end to be in node set NHIST.

The second forming stage requires the rigid tools PUNCH2, DIE2, and DOMER to be in element sets with the same names. The node sets containing the corresponding reference nodes are REFP2, REFD2, and REFDOMER. Create element sets SPRING and DASHPOT containing the spring and dashpot elements, respectively.

“Loading rates,” Section 7.2, discusses the procedures for determining the appropriate step time for a quasi-static process. We can determine an approximate lower bound on step time duration if we know the lowest natural frequency, the fundamental frequency, of the blank. One way to obtain such information is to run a frequency analysis in ABAQUS/Standard. In this forming analysis the punch deforms the blank into a shape similar to the lowest mode. Therefore, it is important that the time for the first forming stage is greater than the time period for the lowest mode if you wish to model structural, as opposed to localized, deformation.

Create an ABAQUS/Standard input file called draw_freq_std.inp. The only elements necessary for the frequency analysis are the elements in the blank, which are defined exactly as they are for the forming analysis. The node and element sets are also the same. Create the mesh in your preprocessor based on the mesh components provided in “Mesh design,” Section 7.5.2, and “Node and element sets,” Section 7.5.3.

The following is an appropriate heading for the analysis:

*HEADING Deep drawing of a can bottom -- frequency analysis ABAQUS/Standard SI units (kg, m, s, N)

Element properties

Give each element set appropriate section properties. Create shell section properties for the blank so that it refers to a material called STEEL (to be defined later), uses five-point Gauss integration, and has a thickness of 0.5 mm.

*SHELL SECTION, ELSET=BLANK, MATERIAL=STEEL, SECTION INTEGRATION=GAUSS .0005, 5

Material properties

The blank is modeled using only the elastic material model since a *FREQUENCY analysis is a linear perturbation step and, thus, ignores nonlinear material properties. Use the following data to define the elastic and mass properties of the steel:

*MATERIAL, NAME=STEEL *ELASTIC 210.0E9, 0.3 *DENSITY 7800.,

Boundary conditions

Apply symmetry boundary conditions to node set BSYM, and fix node set BEND in the axial, or 2-, direction.

*BOUNDARY BSYM, 1 BSYM, 6 BEND, 2

History definition

The history definition defines the *FREQUENCY procedure type to extract the first eigenmode. Request *RESTART output and the nodal displacements of the blank as field output to the output database file, and suppress other output.

*STEP *FREQUENCY 1, *RESTART, WRITE *OUTPUT, FIELD *NODE OUTPUT, NSET=BLANK U, *EL PRINT, FREQUENCY=0 *NODE PRINT, FREQUENCY=0 *END STEP

Run the *FREQUENCY analysis

Save your frequency analysis input in a file named draw_freq_std.inp, and run the analysis using the following command:

abaqus job=draw_freq_std

Postprocessing

When the analysis has completed, use ABAQUS/Viewer to plot the shape of mode 1. Start ABAQUS/Viewer by typing

abaqus viewer odb=draw_freq_stdat the operating system prompt.

To plot the mode shape:

From the main menu bar, select Result Step/Frame.

Step/Frame.

The Step/Frame dialog box appears. Select mode 1, and click OK.

From the main menu bar, select Plot Deformed Shape; or use the

Deformed Shape; or use the ![]() tool in the toolbox.

tool in the toolbox.

ABAQUS/Viewer displays the deformed model shape for the first buckling mode. Superimpose the undeformed model shape on the deformed model shape.

From the main menu bar, select Options Deformed Shape.

Deformed Shape.

The Deformed Shape Plot Options dialog box appears.

Toggle on Superimpose undeformed plot.

Click OK.

ABAQUS/Viewer displays an image of the deformed model of the blank superimposed upon the undeformed model of the blank.

The frequency analysis shows that the blank has a fundamental frequency of 304 Hz, corresponding to a period of 0.0033 s. Figure 7–12 shows the displaced shape of the first mode. We now know that the lower bound on the step time for the first forming stage is 0.0033 s.

The first forming input file, draw_stage1_attempt.inp, will model only the first forming stage; thus, it requires only the components involved in the first forming stage. Use the same mesh for the blank as you used in the frequency extraction input file, draw_freq_std.inp. Create the additional mesh components provided in “Mesh design,” Section 7.5.2, and “Node and element sets,” Section 7.5.3, using your preprocessor. In this section we will review your model definition, make any corrections, and include additional information.

Model description

The following would be a suitable description for the simulation:

*HEADING Deep drawing of a can bottom -- stage 1, attempt 1 SI units (kg, m, s, N)This description clearly labels the input data and indicates the units.

Element properties

Give each element set appropriate section properties. Create shell section properties for the blank so that it refers to a material called STEEL (to be defined later), uses five-point Gauss integration, and has a thickness of 0.5 mm. Five section points through the shell thickness should provide accurate results for a body that will incur significant plasticity.

*SHELL SECTION, ELSET=BLANK, MATERIAL=STEEL, SECTION INTEGRATION=GAUSS .0005, 5

Material properties

The blank, which is the only deformable body in this simulation, is modeled using an elastic-plastic material model. Use the following data to define the elastic and mass properties of the steel:

*MATERIAL, NAME=STEEL *ELASTIC 210.0E9, 0.3 *DENSITY 7800.,Include the plasticity data under the *PLASTIC option.

*PLASTIC 0.912E8, 0.0 0.131E9, 0.159E-02 0.171E9, 0.649E-02 0.211E9, 0.177E-01 0.251E9, 0.395E-01 0.291E9, 0.776E-01 0.331E9, 0.139 0.391E9, 0.295

Figure 7–13 shows that the plasticity curve for this example is quite smooth.

Because smoothness is desired for all aspects of a quasi-static problem, it is advantageous to have as smooth a plasticity curve as possible. With a smooth plasticity curve the material stiffness changes only slightly from one increment to the next as plastic straining occurs, thus helping to produce a solution with less noise.Surface definitions

Use the *SURFACE option to define the analytical surfaces of the rigid tools.

*SURFACE, TYPE=SEGMENTS, NAME=PUNCH1 START,0.032,0.03025 LINE,0.032,0.00625 CIRCL,0.026,0.00025,0.026,0.00625 LINE,0.,0.00025 *SURFACE, TYPE=SEGMENTS, NAME=DIE1 START,0.0326,-0.02825 LINE,0.0326,-0.00425 CIRCL,0.0366,-0.00025,0.0366,-0.00425 LINE,0.050,-0.00025

To bind an analytical surface to a rigid body, assign the name of the analytical surface to the ANALYTICAL SURFACE parameter on the *RIGID BODY option. Use the REF NODE parameter to specify the rigid body reference node that will control the motion of the rigid body.

*RIGID BODY, ANALYTICAL SURFCE=PUNCH1, REF NODE=<reference node number> *RIGID BODY, ANALYTICAL SURFACE=DIE1, REF NODE=<reference node number>

Define the surfaces on the top and bottom of the blank. The surfaces on the top and bottom of the blank must face PUNCH1 and DIE1, respectively.

*SURFACE, NAME=BLANK_TOP BLANK, <SPOS or SNEG> *SURFACE, NAME=BLANK_BOT BLANK, <SPOS or SNEG>Two surface definitions (one on the top and the other on the bottom of the blank) are required because double-sided surfaces can be defined only on three-dimensional shell, membrane, or rigid elements.

Initial fixed boundary conditions

The initial fixed boundary conditions can be part of the model definition or history definition. Since the model is axisymmetric, you must constrain each of the bodies—the blank, punch 1, and die 1—from motion in the radial, or 1-, direction and from in-plane rotation (degree of freedom 6). In addition, constrain die 1 from motion in the axial, or 2-, direction.

*BOUNDARY REFP1, 1 REFP1, 6 REFD1, 1, 6 BSYM, 1 BSYM, 6

Several aspects of the loading history are not clearly defined from the model description. Therefore, the analysis will include some amount of trial and error to help determine what produces acceptable results and what does not. Unlike the other example problems in this manual, we will discuss this forming problem one step at a time, becoming satisfied with the results from one step before continuing to the next step.

The goal of the first forming stage is to form a cup with a depth of 0.015 m using punch 1 and die 1. We intentionally did not provide a punch velocity in the problem description because an appropriate punch velocity for a quasi-static analysis is not necessarily the same as the actual punch velocity. Typical punch velocities are on the order of 0.1–1.0 m/s, although actual velocities vary.

To analyze the first forming stage successfully, we must consider the following questions:

What is an appropriate step time?

How should we move the punch?

How many increments and how much computer time will the analysis require?

What output should we request?

Determining an appropriate step time

In “Determining an appropriate step time,” Section 7.5.4, we performed a frequency analysis, which showed that the blank has a fundamental frequency of 304 Hz, corresponding to a time period of 0.0033 s. This time period provides a lower bound on the step time for the first forming stage. Choosing the step time to be 10 times the time period of the fundamental natural frequency, or 0.033 s, should ensure a quality quasi-static solution. This time period corresponds to a constant punch velocity of 0.45 m/s, which is typical for metal forming.

Moving the punch

Even if the punch actually moves at a nearly constant velocity, it is desirable to use a different amplitude curve that allows the blank to accelerate more smoothly. When considering what type of loading amplitude to use, remember that smoothness is important in all aspects of a quasi-static analysis. The preferred approach is to move the punch as smoothly as possible the desired distance in the desired amount of time. We will analyze the first forming stage using both approaches—a constant punch velocity of 0.45 m/s and a smoothly ramped punch velocity using a SMOOTH STEP amplitude—and will compare the results.

Computer time

Before you run the forming analysis, you may wish to know how many increments the analysis will take and, consequently, how much computer time the analysis requires. You can run a datacheck analysis to obtain the approximate value for the initial stable time increment, or you can estimate it using the relations in “Mass scaling,” Section 7.3. Knowing the stable time increment, which in this case does not change much from increment to increment, you can determine how many increments are required to complete the forming stage. Once the analysis begins, you can get an idea of how much CPU time is required per increment and, consequently, how much CPU time the step requires.

Using the relations stated in “Mass scaling,” Section 7.3, the stable time increment for this analysis is approximately 1 × 10–7 s. Therefore, the forming stage requires approximately 330,000 increments for a step time of 0.033 s.

Output

To help determine how closely the analysis approximates the quasi-static assumption, the various energy histories are useful. Especially useful is comparing the kinetic energy to the internal strain energy. Another useful history plot is that of the velocities at typical nodes. Earlier you created the node set, NHIST, containing nodes at which you will obtain velocity histories. Such output gives you an idea of the severity of any velocity spikes in the solution. Write these energy and velocity histories as history data to the output database file. Write the section forces, shell thicknesses, and nodal displacements to the output database as field data for postprocessing with ABAQUS/Viewer. You should also have ABAQUS save the state information so that you can restart the analysis. For your first attempt request state information at 20 intervals. Once you are more confident with the first forming stage, you can decrease this value. Define the reference node for the rigid surface PUNCH1 as the monitor node.

For the first forming stage we present a progression of three attempts to obtain an acceptable solution. In the first attempt we move the punch with a constant velocity. Seeking to diminish the severe oscillations of the first attempt, in the second attempt we smooth the punch velocity amplitude by setting the DEFINITION parameter on the *AMPLITUDE option equal to SMOOTH STEP. To further remove high-frequency oscillations, in the third attempt we introduce stiffness proportional damping. The results of the third attempt are acceptable, and they are subsequently used as a basis of comparison for analyses with varying degrees of mass scaling. If you do not wish to run analyses that do not produce acceptable results, read the discussions for attempts 1 and 2 but run only attempt 3.

The history definition for each of the attempts contains the same contact definitions and output requests. The history definition begins with the *STEP option; the *DYNAMIC, EXPLICIT procedure; and a total step time of 10 times the fundamental natural frequency, or 0.033 s.

*STEP *DYNAMIC, EXPLICIT , .033

Define contact between the top of the blank and the punch and between the bottom of the blank and the die.

*CONTACT PAIR, INTERACTION=INTER PUNCH1, BLANK_TOP DIE1, BLANK_BOT

Define a friction coefficient of 0.1 between all contacting surfaces.

*SURFACE INTERACTION, NAME=INTER *FRICTION .1,

Write the restart information at 10 evenly spaced intervals during the analysis by including the following line in your input file:

*RESTART, WRITE, NUMBER INTERVAL=10

Request velocity and displacement history output for node set NHIST and energy history output every 1 × 10–5 s.

*OUTPUT, HISTORY, TIME INTERVAL=1.E-5 *NODE OUTPUT, NSET=NHIST U,V *ENERGY OUTPUT ALLKE,ALLIE,ALLWK,ALLVD,ALLAE,ALLPD,ETOTAL

Request section force and shell thickness field output for element set BLANK and displacement output at 4 intervals during the step.

*OUTPUT, FIELD, NUMBER INTERVAL=4 *ELEMENT OUTPUT, ELSET=BLANK STH, SF *NODE OUTPUT U,RF *END STEP

Add the following amplitude to the model definition to simulate the punch moving at a constant velocity of 0.45 m/s:

*AMPLITUDE, NAME=FORM1 0., 0., .033, 1.and add the following prescribed displacement boundary condition to the history definition:

*BOUNDARY, TYPE=DISPLACEMENT, AMPLITUDE=FORM1 REFP1, 2, 2, -0.015

Save your input in a file named draw_stage1_attempt1.inp, and run the analysis. Thirty minutes or more may be required to run this analysis to completion.

Strategy for evaluating the results

Before looking at the results that are ultimately of interest, such as stresses and deformed shapes, we need to determine whether or not the solution is close enough to being quasi-static to be acceptable. One good approach is to compare the kinetic energy history to the internal energy history. In a metal forming analysis most of the internal energy is due to plastic deformation. Since punch 1 has no mass, the blank is the only body with mass; and the kinetic energy is solely due to the motion of the blank. To indicate an acceptable quasi-static solution, the kinetic energy of the blank should be no greater than a few percent of the internal energy. For greater accuracy, especially when springback stresses are of interest, the kinetic energy should be lower. This approach is very useful because it is general for all types of metal forming processes and does not require any intuitive understanding of the stresses in the model; many forming processes may be too complex to permit an intuitive feel for the results.

While a good primary indication of the caliber of a quasi-static analysis, the ratio of kinetic energy to internal energy alone is not adequate to confirm the quality. You should also evaluate the two energies independently to determine whether they are reasonable. This part of the evaluation takes on increased importance when accurate springback stress results are needed because an accurate springback stress solution is highly dependent on accurate plasticity results. Even if the kinetic energy is fairly small, if it is highly oscillatory, the model could be experiencing significant plasticity. Generally, we expect smooth loading to produce smooth results; if the loading is smooth but the energy results are oscillatory, the results may be inadequate. Since an energy ratio is incapable of showing such behavior, you should also study the kinetic energy history itself to see whether it is smooth or noisy.

If the kinetic energy does not indicate quasi-static behavior, it can be useful to look at velocity histories at some nodes to get an understanding of the model's behavior in various regions. Such velocity histories can indicate which regions of the model are oscillating and causing the high kinetic energies.

Evaluating the results for attempt 1

In ABAQUS/Viewer, select File Open from the main menu bar; or use the

Open from the main menu bar; or use the ![]() tool from the toolbar to open the output database draw_stage1_attempt1.odb. Plot the kinetic energy and the internal energy.

tool from the toolbar to open the output database draw_stage1_attempt1.odb. Plot the kinetic energy and the internal energy.

To create an energy history plot:

From the main menu bar, select Plot History Output.

History Output.

A history plot of the external work for the whole model appears.

From the main menu bar, select Result History Output.

History Output.

The History Output dialog box appears.

From the list of available variables, select Kinetic energy: ALLKE for Whole Model.

Skipping frames between reads keeps any high frequency oscillation from becoming simply a blackened region on the graph. Skip 7 frames between reads.

Click Plot to create a history plot of ALLKE.

A history plot of the kinetic energy for the whole model appears (see Figure 7–14).

Click Dismiss to close the dialog box.

Similarly, create a history plot of the model internal energy, ALLIE (see Figure 7–15).

Figure 7–14 shows the kinetic energy history, which is very noisy through the first half of the step before becoming smooth. That the kinetic energy history has no clear relation to the forming of the blank is an indication of the inadequacy of this analysis. In this analysis the punch velocity remains constant, while the kinetic energy—which is due to the blank entirely since the punch has no mass—is far from constant.

Figure 7–15 shows the internal energy history. Without anything further to which to compare the internal energy, it appears reasonable, although it is not clear why the slope changes at 8 ms.

Comparing Figure 7–14 and Figure 7–15 shows that the kinetic energy is a small fraction (less than 1%) of the internal energy through all but the very beginning of the analysis. The criterion that kinetic energy must be small relative to internal energy has been satisfied, even for this severe loading case.

Since the kinetic energy history is very noisy, it is useful to look at the velocity history of a node in the model to gain an understanding of the blank's motion. Plot the vertical velocity (V2) history of the first node in node set NHIST, which is a node in the central region of the blank (Figure 7–16).

To create a history plot of the velocity:

From the main menu bar, select Result History Output.

History Output.

From the list of available variables in the History Output dialog box, select Spatial velocity: V2 at Node 521 in NSET NHIST.

Click Plot to create a history plot of V2.

The velocity of the node oscillates between values as great as ±10 m/s, while the punch velocity remains constant. Such noisy behavior has a strong effect on the results in this case, since the material includes plasticity. These results indicate that we must change the simulation in some way to obtain a smoother response.

For attempt 2 smooth the velocity amplitude of the punch. Instead of moving the punch with a constant velocity, use the SMOOTH STEP amplitude definition. Refer to “Smooth amplitude curves,” Section 7.2.1, for an explanation of this amplitude definition. By specifying an amplitude of 0.0 at the beginning of the step and an amplitude of 1.0 at the end of the step, ABAQUS/Explicit creates an amplitude definition that is smooth in both its first and second derivatives. Therefore, using SMOOTH STEP for the displacement control also assures us that the velocity and acceleration are smooth. Change the amplitude definition to

*AMPLITUDE, NAME=FORM1, DEFINITION=SMOOTH STEP 0., 0., .033, 1.

Save your modified input in a file named draw_stage1_attempt2.inp, and run the analysis. Thirty minutes or more may be required to run this analysis to completion.

Evaluating the results for attempt 2

The kinetic energy history shown in Figure 7–17 is still quite noisy, although somewhat different from that of attempt 1. The noise dies out by 20 ms, and the kinetic energy drops to zero. Near the end of the analysis it again becomes noisy.

The internal energy for attempt 2, shown in Figure 7–18, is similar to that of attempt 1. The internal energy history has a few unexplained bumps, rather than the expected smooth increase. Again, the ratio of kinetic energy to internal energy is quite small and appears to be acceptable.

For many forming analyses a smooth loading velocity, such as that used in attempt 2, is adequate to produce a quasi-static forming step. However, this particular forming process is somewhat less well-behaved than many because of the lack of a blank holder. Figure 7–19 shows the velocity history of the second node in node set NHIST, which contains the node at the free end of the blank.

The node oscillates greatly because the end of the blank is unconstrained. If this forming process had a blank holder, attempt 2 would most likely provide acceptable results. However, since this process lacks such a constraint, we must make additional changes to produce an acceptable quasi-static solution.

To decrease the high-frequency noise caused primarily by the oscillations of the blank's free end, add stiffness proportional damping to the material definition of the blank. It is best to use the smallest amount of damping possible to obtain the desired solution since increasing the stiffness damping decreases the stable time increment and, thus, increases the computer time.

(Another available type of material damping is mass proportional damping, which generally is used to decrease the low-frequency oscillations. Adding mass damping is akin to executing the forming process in a viscous fluid. The problem with mass proportional damping in metal forming analyses is the difficulty in determining whether or not the mass proportional damping has adversely influenced the solution. Therefore, we discourage the use of mass proportional damping in forming analyses unless it is absolutely necessary.)

To avoid a dramatic drop in the stable time increment, the stiffness proportional damping factor, ![]() , should be less than, or of the same order of magnitude as, the initial stable time increment without damping. Since the initial stable time increment for attempt 2 reported in the status file is 1.05 × 10–7, use the following stiffness proportional damping for attempt 3:

, should be less than, or of the same order of magnitude as, the initial stable time increment without damping. Since the initial stable time increment for attempt 2 reported in the status file is 1.05 × 10–7, use the following stiffness proportional damping for attempt 3:

*DAMPING, BETA=1.E-7The *DAMPING option should form part of the material definition of the problem.

Save your modified input in a file, draw_stage1_attempt3.inp, and run the analysis.

Evaluating the results for attempt 3

The kinetic energy history shown in Figure 7–20 is much smoother and corresponds to the punch velocity much better than the previous attempts, though there is still some high frequency oscillation.

The internal energy history, shown in Figure 7–21, shows a smooth increase from zero up to the final value. Most of the internal energy is dissipated by plasticity. Again, the kinetic energy is small relative to the internal energy. These results appear to be acceptable.

History plots of the other energy variables reveal that the energy absorbed by viscous dissipation is small relative to the internal energy. This confirms that the amount of stiffness proportional damping included in this model has not adversely affected the results. In addition, the amount of energy used to control hourglassing is zero; thus, hourglassing is not a problem in this analysis.

Before continuing the forming process with the springback analysis, we will discuss what we have learned from the three attempts at forming stage 1.

Our initial criteria for evaluating the acceptability of the results was that the kinetic energy should be small compared to the internal energy. What we found was that even for the most severe case, attempt 1, this condition seems to have been met adequately. For many forming analyses that are better constrained—for example, with a blank holder—keeping the kinetic energy to internal energy ratio small may be an adequate condition to obtain a good solution to the forming problem. However, in this simulation the high frequency oscillations proved to have a strong effect on the solution, doubling the internal energy of the blank, as shown in Figure 7–22. Without damping these oscillations, the solution is not quasi-static.

The additional requirements—that the histories of kinetic energy and internal energy must be appropriate and reasonable—are very useful and necessary, but they also increase the subjectivity of evaluating the results. Enforcing these requirements in general for more complex forming processes may be difficult because these requirements demand some intuition regarding the behavior of the forming process.

Results of forming stage 1

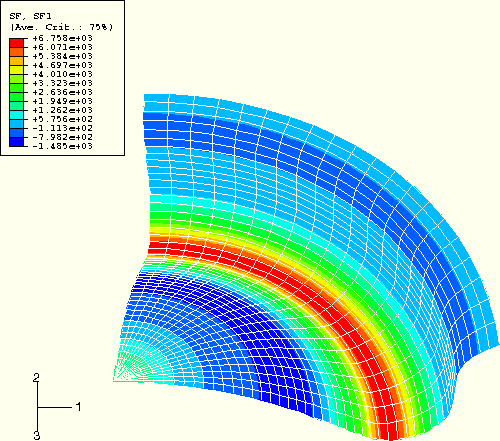

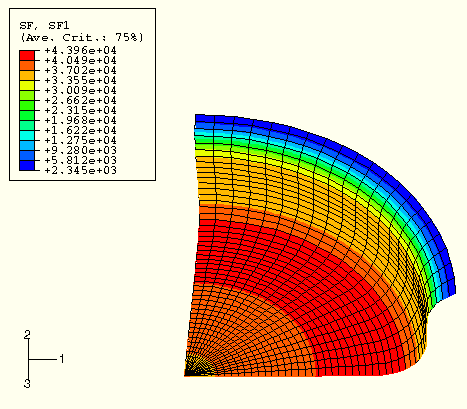

Now that we are satisfied that the quasi-static solution for the first forming stage is adequate, study some of the other results of interest. Figure 7–23 shows a contour plot of SF1, which is the force summation through the entire thickness of the element in the radial direction, or the local 1-direction. The axisymmetric model has been swept 90° for visualization purposes.

Figure 7–23 Contour plot of SF1 (section force in the radial direction) for forming stage 1, attempt 3 (swept model for visualization purposes only).

To contour the section force:

First, restrict the display group to the elements representing the blank. From the main menu bar, select Tools Display Group

Display Group Create.

Create.

The Create Display Group dialog box appears.

Select the element set PART-1-1.BLANK, and click Replace to replace the current model display with the element set PART-1-1.BLANK.

Now, the element set PART-1-1.BLANK is the only member of the display group.

From the main menu bar, select Result Field Output.

Field Output.

The Field Output dialog box appears.

Select SF from the Output Variable list.

From the list of available components, select SF1.

Click OK to apply these settings.

The Select Plot Mode dialog box appears.

Toggle on Contour, and click OK.

To better visualize contours in axisymmetric models, sweep the shell elements to construct the equivalent three-dimensional view. You can extrude two-dimensional elements in a similar fashion.

From the main menu bar, select View ODB Display Options.

ODB Display Options.

The ODB Display Options dialog box appears.

Click the Sweep & Extrude tab.

In the General Sweep region, toggle on Sweep elements and set the sweep range from 0 to 90 degrees.

Click OK to apply these settings.

The view shown in Figure 7–23 can be specified.

From the main menu bar, select View Specify.

Specify.

The Specify View dialog box appears.

Using the Rotation Angles method, enter the X-, Y-, and Z- angles as 45, 0, 0.

Click OK.

ABAQUS displays your model in the specified view.

The plot shows that SF1 is nearly constant at a value of approximately 3.274 × 104 in the flat region near the symmetry line. We would expect SF1 to be fairly high and positive in this region because of the uniform stretching. Since the blank is formed in a smooth manner, we would expect SF1 to vary smoothly, as it does. It also is reasonable that SF1 drops to a lower value toward the free end of the blank.

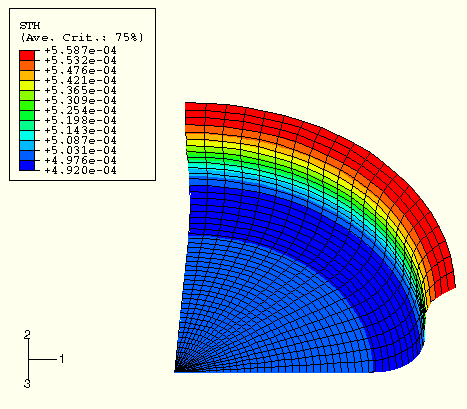

Figure 7–24 shows a contour plot of the shell thickness, STH. At the start of the analysis the blank had a uniform shell thickness of 0.5 mm.

Figure 7–24 Contour plot of STH (shell thickness) for forming stage 1, and attempt 3 (swept model for visualization purposes only).

Now that we have obtained an acceptable solution to the first forming stage, we can try to obtain similar acceptable results using less computer time. Most forming analyses require too much computer time to be run in their physical time scale because the actual time period of forming events is large by explicit dynamics standards; running in an acceptable amount of computer time often requires making changes to the input file to reduce the computer cost of the analysis. There are two ways to reduce the cost of the analysis:

Artificially increase the punch velocity so that the same forming process occurs in a shorter step time. This method is called load-rate scaling.

Artificially increase the mass density of the elements so that the stability limit increases, allowing the analysis to take fewer increments. This method is called mass scaling.

Unless the model has rate-dependent materials or damping, these two methods effectively do the same thing. Our model has no rate-dependent materials but does contain rate-dependent damping due to the dashpot in the second forming stage. Since scaling the loading rate would change the velocities and, hence, the force in the dashpot, we will use mass scaling instead, which will not affect the force in the dashpot.

Determining acceptable mass scaling

“Loading rates,” Section 7.2, and “Metal forming problems,” Section 7.2.3, discuss how to determine acceptable scaling of the loading rate or mass to accelerate the time scale of a quasi-static analysis. The goal is to model the process in the shortest time period in which inertial forces remain insignificant. There are bounds on how much the solution time can be increased while still obtaining a meaningful quasi-static solution.

As discussed in “Loading rates,” Section 7.2, we can use the same methods to determine an appropriate mass scaling factor as we would use to determine an appropriate load-rate scaling factor. The difference between the two methods is that a load-rate scaling factor of f has the same effect as a mass scaling factor of ![]() . Originally, we assumed that a step time of 10 times the period of the fundamental frequency of the blank would be adequate to produce quasi-static results. By studying the model energies and other results, we were satisfied that these results were acceptable. This technique produced a punch velocity of approximately 0.5 m/s, which is typical of actual punch velocities. Now we will accelerate the solution time using mass scaling and compare the results against our unscaled solution to determine whether the scaled results are acceptable. We assume that scaling can only diminish, not improve, the quality of the results. The objective is to use scaling to decrease the computer time and still produce acceptable results.

. Originally, we assumed that a step time of 10 times the period of the fundamental frequency of the blank would be adequate to produce quasi-static results. By studying the model energies and other results, we were satisfied that these results were acceptable. This technique produced a punch velocity of approximately 0.5 m/s, which is typical of actual punch velocities. Now we will accelerate the solution time using mass scaling and compare the results against our unscaled solution to determine whether the scaled results are acceptable. We assume that scaling can only diminish, not improve, the quality of the results. The objective is to use scaling to decrease the computer time and still produce acceptable results.

Our goal is to determine what scaling values still produce acceptable results and at what point the scaled results become unacceptable. To see the effects of both acceptable and unacceptable scaling factors, we investigate a range of scaling factors on the stable time increment size from ![]() to 30; specifically, we choose

to 30; specifically, we choose ![]() , 10, and 30. These speedup factors translate into mass scaling factors of 10, 100, and 900, respectively.

, 10, and 30. These speedup factors translate into mass scaling factors of 10, 100, and 900, respectively.

To apply mass scaling of 10, add the following option to the history definition,

*FIXED MASS SCALING, FACTOR=10and save the modified input in a file named draw_stage1_attempt3_sqrt10.inp; run draw_stage1_attempt3_10.inp and draw_stage1_attempt3_30.inp, which have mass scaling factors of 100 and 900, respectively.

First we will look at the effect of mass scaling on the section forces and the displaced shape. We will then see whether the energy histories provide a general indication of the analysis quality.

Evaluating the results with mass scaling

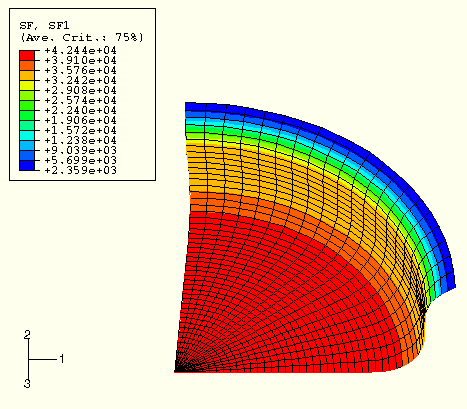

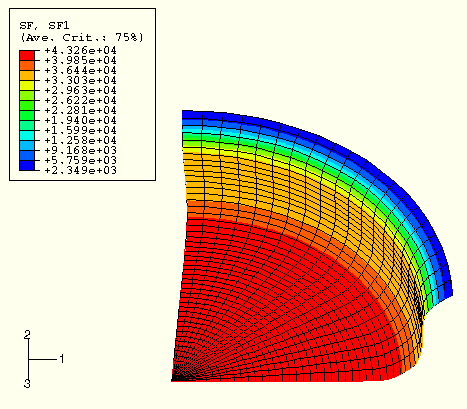

One of the results of interest in this analysis is the radial section force, SF1. Since we have already seen the contour plot of SF1 at the completion of the unscaled analysis in Figure 7–23, we can compare the results from each of the scaled analyses with the unscaled analysis results. These contour plots display the results in the form of bands on the displaced mesh. Therefore, these SF1 contour plots also provide the displaced shape of the mesh. Figure 7–26 shows SF1 for a speedup of ![]() (mass scaling of 10), Figure 7–27 shows SF1 for a speedup of 10 (mass scaling of 100), and Figure 7–28 shows SF1 for a speedup of 30 (mass scaling of 900). These plots indicate that a speedup of

(mass scaling of 10), Figure 7–27 shows SF1 for a speedup of 10 (mass scaling of 100), and Figure 7–28 shows SF1 for a speedup of 30 (mass scaling of 900). These plots indicate that a speedup of ![]() produces results that are very similar to the unscaled results. For a speedup of 10 the results are similar, but the section force at the symmetry axis drops noticeably. For a speedup of 30 the section force results are quite different, indicating that this level of speedup is clearly too high.

produces results that are very similar to the unscaled results. For a speedup of 10 the results are similar, but the section force at the symmetry axis drops noticeably. For a speedup of 30 the section force results are quite different, indicating that this level of speedup is clearly too high.

Figure 7–26 Section force SF1 for speedup of ![]() (mass scaling of 10; swept model for visualization purposes only).

(mass scaling of 10; swept model for visualization purposes only).

Figure 7–27 Section force SF1 for speedup of 10 (mass scaling of 100; swept model for visualization purposes only).

Figure 7–28 Section force SF1 for speedup of 30 (mass scaling of 900; swept model for visualization purposes only).

Now that we have seen how mass scaling has affected some of the section force results, we will see whether the energy histories provide the same indication of analysis quality. Figure 7–29 shows the histories of kinetic energy and internal energy for all of the scaled analyses. The internal energy is almost identical for all three cases, whereas the kinetic energy increases from nearly zero for a speedup of ![]() to a maximum of approximately 7.0 for a speedup of 30.

to a maximum of approximately 7.0 for a speedup of 30.

Discussion of speedup methods

As the mass scaling increases, the solution time decreases. The quality of the results also decreases because dynamic effects become more prominent, but there is usually some level of scaling that improves the solution time without sacrificing the results. Clearly, a speedup of 30 is too great to produce quasi-static results for this analysis.

A smaller speedup, such as ![]() , does not alter the results significantly. These results would be adequate for most applications, including springback analyses. With a scaling factor of 10 the quality of the results begins to diminish, while the general magnitudes and trends of the results remain intact. Correspondingly, the ratio of kinetic energy to internal energy increases noticeably. The results for this case would be adequate for many applications but not for accurate springback analysis.

, does not alter the results significantly. These results would be adequate for most applications, including springback analyses. With a scaling factor of 10 the quality of the results begins to diminish, while the general magnitudes and trends of the results remain intact. Correspondingly, the ratio of kinetic energy to internal energy increases noticeably. The results for this case would be adequate for many applications but not for accurate springback analysis.

While it is possible to perform springback analyses within ABAQUS/Explicit, ABAQUS/Standard is much more efficient at solving springback analyses. Since springback analyses are simply static simulations without external loading or contact, ABAQUS/Standard can obtain a springback solution in just a few increments. Conversely, ABAQUS/Explicit must obtain a dynamic solution over a time period that is long enough for the solution to reach a steady state. For efficiency ABAQUS has the capability to import results back and forth between ABAQUS/Explicit and ABAQUS/Standard, allowing us to perform forming analyses in ABAQUS/Explicit and springback analyses in ABAQUS/Standard.

We will create a new input file that imports the results from the analysis with a speedup of ![]() (mass scaling of 10, draw_stage1_attempt3_sqrt10.inp) and perform a springback analysis.

(mass scaling of 10, draw_stage1_attempt3_sqrt10.inp) and perform a springback analysis.

Model definition

The first option following *HEADING is the *IMPORT option, which reads the element definitions and the state from the corresponding ABAQUS/Explicit analysis. Your import input file should begin with the following:

*HEADING Deep drawing of a can bottom -- first springback ABAQUS/Standard springback following draw_stage1_attempt3_sqrt10.inp SI units (kg, m, s, N) *IMPORT, STEP=1, INTERVAL=10, STATE=YES, UPDATE=NO BLANK, *IMPORT ELSET BLANK, *IMPORT NSET BSYM, NHIST

Setting the STATE parameter equal to YES causes the state of the model—stresses, strains, etc.—to be imported. Setting the UPDATE parameter equal to NO causes the strains and displacements to be imported as well instead of being reset to zero. The data line following the *IMPORT option supplies the name of the element set containing the elements that are to be imported. The data line following the *IMPORT ELSET option lists element set names to be imported; the *IMPORT NSET option likewise identifies node set names to be imported.

History definition

You must redefine the boundary conditions, which are not imported. Impose the same symmetry boundary conditions as were imposed in the ABAQUS/Explicit input file.

*BOUNDARY BSYM, 1 BSYM, 6

For output, write the final state of the model to the restart file.

*RESTART, WRITE, FREQUENCY=999

The history definition is quite straightforward since no loads are applied. Use the following history definition:

*STEP, NLGEOM *STATIC .1, 1. *BOUNDARY, FIXED BSYM, 2, 2 *OUTPUT, FIELD, FREQUENCY=10 *ELEMENT OUTPUT, ELSET=BLANK STH, SF *NODE OUTPUT U, *END STEP

The NLGEOM parameter is used on the *STEP option since the ABAQUS/Explicit analysis used it (this is the default setting in ABAQUS/Explicit). In general, it is safer to include the NLGEOM parameter because we do not always know whether or not geometric nonlinearities will affect the results. To remove rigid body motion, it is necessary to fix the blank in the 2-direction. Fix the blank at just a single point, such as node set BSYM, so that you impose no unnecessary constraints. It is important to use the FIXED parameter on the *BOUNDARY option so that BSYM is fixed at its final position at the end of forming stage 1. If you were to omit the FIXED parameter, BSYM would return to its original location prior to deformation. Either fixing BSYM at its final position from the previous stage or moving it back to its undeformed location will produce the same springback results; however, fixing BSYM at its final position retains the necessary continuity in the blank location through the stages of this simulation.

Save your input in a file named draw_spring1_std.inp, and run the analysis using the following command:

abaqus job=draw_spring1_std oldjob=draw_stage1_attempt3_sqrt10

Results of the springback analysis

Figure 7–30 shows a contour plot of SF1 at the end of the springback analysis in ABAQUS/Standard. These results are necessarily dependent on the accuracy of the forming stage preceding it. In fact, springback results are highly sensitive to errors in the forming stage, more sensitive than the results of the forming stage itself.

Now that we are satisfied with the results for forming stage 1 with a speedup of ![]() (mass scaling of 10) and its corresponding springback, we continue the simulation with annealing and forming stage 2 using ABAQUS/Explicit. We will create a new input file that imports the final springback condition from ABAQUS/Standard and continue the analysis from that point.

(mass scaling of 10) and its corresponding springback, we continue the simulation with annealing and forming stage 2 using ABAQUS/Explicit. We will create a new input file that imports the final springback condition from ABAQUS/Standard and continue the analysis from that point.

Model definition

Import the model from the final increment of the springback analysis. Set the STATE parameter equal to YES so that the stress and strain state of the model is imported. Set the UPDATE parameter equal to NO so that the displacements are continuous. Begin your restart input file with the following *HEADING and *IMPORT option blocks:

*HEADING Deep drawing of a can bottom -- stage 2 ABAQUS/Explicit annealing and forming stage 2 following draw_spring1_std.inp SI units (kg, m, s, N) *IMPORT, STATE=YES, UPDATE=NO BLANK,

Since you are importing only the blank from the ABAQUS/Standard analysis, you must define the rigid tooling needed for forming stage 2 and the necessary node and element sets as shown in Figure 7–11.

*RIGID BODY, ELSET=PUNCH2, REF NODE=<reference node number> *RIGID BODY, ELSET=DIE2, REF NODE=<reference node number> *RIGID BODY, ELSET=DOMER, REF NODE=<reference node number>

Define the surfaces on the blank and the rigid tools.

*SURFACE, NAME=BLANK_TOP BLANK, <SPOS or SNEG> *SURFACE, NAME=BLANK_BOT BLANK, <SPOS or SNEG> *SURFACE, NAME=PUNCH2 PUNCH2, <SPOS or SNEG> *SURFACE, NAME=DIE2 DIE2, <SPOS or SNEG> *SURFACE, NAME=DOMER DOMER, <SPOS or SNEG>

You must also define the spring and dashpot on which die 2 sits. These are defined as a SPRINGA and a DASHPOTA element, each with one end attached to the reference node for die 2 (node set REFD2) and one end attached to ground (node set SPEND).

*ELEMENT, TYPE=SPRINGA, ELSET=SPRING <element number>,<node # of REFD2>,<node # of SPEND> *SPRING, ELSET=SPRING 2, 6.3E6, *ELEMENT, TYPE=DASHPOTA, ELSET=DASHPOT <element number>,<node # of REFD2>,<node # of SPEND> *DASHPOT, ELSET=DASHPOT 2, 1.E4,

Define the 10 kg mass associated with die 2.

*ELEMENT, TYPE=MASS, ELSET=MASS <element number>,<node # of REFD2> *MASS, ELSET=MASS 10.,

You must define any desired sets for postprocessing.

*NSET, NSET=REF REFP2, REFD2, REFDOMER, SPENDBefore proceeding, you must make certain that the rigid tools are positioned properly by defining a brief step that includes only the rigid body motion of the tools. Since only rigid body motion occurs in this first step, the time period for the step can be very short. We have chosen 1 × 10–6 s as the step time. Include the following amplitude definition in the model definition part of your input file:

*AMPLITUDE, NAME=RIGID, DEFINITION=SMOOTH STEP 0., 0., 1.E-6, 1.In addition, define an amplitude for the forming stage.

*AMPLITUDE, NAME=FORM2, DEFINITION=SMOOTH STEP 0., 0., .033, 1.

History definition

Since an *ANNEAL step cannot be the first step in an ABAQUS/Explicit import analysis, begin the history by moving the rigid tooling into position. Moving the tooling into position is quite straightforward; the difficulty in this case is positioning the tools properly, given the unknown shape of the blank following springback. At the end of the first forming stage the position of the blank is known: the blank has been drawn to a depth of 0.015 m, and it is clamped between two rigid tools whose positions are known. However, during springback the blank is no longer constrained by the rigid tools, and it deforms freely to minimize its internal strain energy. The changes in shape during springback make it necessary to view the displaced shape following springback in ABAQUS/Viewer before positioning the rigid tools for the second forming stage.

After the first step it is imperative that there be no overclosure of contact pairs because, if such overclosure exists, it is resolved in a single increment. Resolving the overclosure results in a large velocity being imposed on an overclosed node, possibly distorting the associated elements and drastically increasing the kinetic energy. On the other hand, computer time is wasted if the rigid bodies are far away from the blank at the start of the step because the analysis runs while no deformation occurs in the blank.

Use Tools Query from the main menu bar in ABAQUS/Viewer to determine the coordinates of some nodes on the blank at the end of springback. The goal is to position the rigid bodies for the second forming stage as close as possible to the deformed blank without any overclosure. Even the slightest overclosure will cause analysis problems. Remember that you must consider the thickness of the shell when positioning the rigid bodies, since ABAQUS/Explicit considers the current shell thickness when performing contact calculations. The forming process is designed so that the curved parts of punch 2 and die 2 form concentric arcs with the blank in between. Punch 2 has a radius of 0.006 m, and it contacts the inner radius of the blank, which also has a radius of approximately 0.006 m after springback. Die 2 has a radius of 0.0065 m, and it contacts the outer radius of the blank, which—given its thickness of approximately 0.0005—also has a radius of approximately 0.0065 m. Include the *DIAGNOSTICS option with the CONTACT INITIAL OVERCLOSURE=DETAIL and DEFORMATION SPEED CHECK=DETAIL parameters to provide detailed information about possible initial overclosures and resulting excessive deformation speeds.

Query from the main menu bar in ABAQUS/Viewer to determine the coordinates of some nodes on the blank at the end of springback. The goal is to position the rigid bodies for the second forming stage as close as possible to the deformed blank without any overclosure. Even the slightest overclosure will cause analysis problems. Remember that you must consider the thickness of the shell when positioning the rigid bodies, since ABAQUS/Explicit considers the current shell thickness when performing contact calculations. The forming process is designed so that the curved parts of punch 2 and die 2 form concentric arcs with the blank in between. Punch 2 has a radius of 0.006 m, and it contacts the inner radius of the blank, which also has a radius of approximately 0.006 m after springback. Die 2 has a radius of 0.0065 m, and it contacts the outer radius of the blank, which—given its thickness of approximately 0.0005—also has a radius of approximately 0.0065 m. Include the *DIAGNOSTICS option with the CONTACT INITIAL OVERCLOSURE=DETAIL and DEFORMATION SPEED CHECK=DETAIL parameters to provide detailed information about possible initial overclosures and resulting excessive deformation speeds.

Use the amplitude definition named “RIGID” with the displacement boundary condition to move the rigid bodies into position. It is important that the velocity is zero at the end of the positioning step since the final velocity in the positioning step is the initial velocity in the second forming stage. Use the following step to position the rigid bodies for forming stage 2:

*STEP *DYNAMIC, EXPLICIT , 1.E-6 *RESTART, WRITE, NUMBER INTERVAL=1 *BOUNDARY, TYPE=VELOCITY BSYM, 1, 2, 0. BSYM, 6, 6, 0. REFDOMER, 1, 1, 0. REFDOMER, 6, 6, 0. REFD2, 1, 1, 0. REFD2, 6, 6, 0. SPEND, 1, 1, 0. REFP2, 1, 1, 0. REFP2, 6, 6, 0. *BOUNDARY, AMPLITUDE=RIGID REFDOMER, 2, 2, <user-determined value> REFD2, 2, 2, <user-determined value> SPEND, 2, 2, <user-determined value> REFP2, 2, 2, <user-determined value> *DIAGNOSTICS, CONTACT INITIAL OVERCLOSURE=DETAIL, DEFORMATION SPEED CHECK=DETAIL *OUTPUT, HISTORY, TIME INTERVAL=1.E-5 *NODE OUTPUT, NSET=NHIST U, V *NODE OUTPUT, NSET=REF U, RF *ENERGY OUTPUT ALLKE, ALLIE, ALLWK, ALLVD, ALLAE, ALLPD, ETOTAL *OUTPUT, FIELD, NUMBER INTERVAL=4 *ELEMENT OUTPUT, ELSET=BLANK STH, SF, S *NODE OUTPUT U, *END STEP

Physically, annealing is the process of heating a metal part to a high temperature to allow the microstructure to recrystallize, removing dislocations caused by cold working of the material. The *ANNEAL procedure removes stresses and plastic strains from all deformable elements in the model without changing the shell thickness or deformed shape. The material properties are assumed to be the same before and after annealing. The *ANNEAL step is quite simple because there are no loadings or output requests permitted. The entire *ANNEAL step is as follows:

*STEP *ANNEAL *END STEP

In the second forming stage the deformed blank is clamped between punch 2 and die 2, which sits on a spring and dashpot. As punch 2 is moved 0.010 m in the negative 2-direction, the blank is forced to move in the negative 2-direction, pressing against the stationary domer in the flat region of the blank. At the end of the second forming stage the blank takes on a dome shape in the previously flat region, while retaining the vertically drawn region from the first forming stage. Since the analysis is similar to the first forming stage, assume that the step time, damping, and mass scaling are the same as for the first forming stage. The loading rate in this stage of the forming simulation is actually slower than that in the first stage because the distance swept by the second punch is shorter while the step time remains the same.

Add the following to your input file for forming stage 2:

*STEP *DYNAMIC, EXPLICIT , .033 *FIXED MASS SCALING, FACTOR=10 *DIAGNOSTICS, CONTACT INITIAL OVERCLOSURE=DETAIL, DEFORMATION SPEED CHECK=DETAIL *CONTACT PAIR, INTERACTION=INTER PUNCH2, BLANK_TOP DIE2, BLANK_BOT DOMER, BLANK_BOT *SURFACE INTERACTION, NAME=INTER *FRICTION .1, *BOUNDARY, TYPE=DISPLACEMENT, AMPLITUDE=FORM2, OP=NEW REFP2, 2, 2, -0.010 *BOUNDARY, TYPE=VELOCITY, OP=NEW REFP2, 1, 1, 0. REFP2, 6, 6, 0. REFD2, 1, 1, 0. REFD2, 6, 6, 0. SPEND, 1, 2, 0. REFDOMER, 1, 6, 0. BSYM, 1, 1, 0. BSYM, 6, 6, 0. *MONITOR, NODE=<node # for REFD2>, DOF=2 *RESTART, WRITE, NUMBER INTERVAL=10 *END STEP

Save your input data in a file called draw_stage2.inp. Run the analysis using the following command:

abaqus job=draw_stage2 oldjob=draw_spring1_std

Evaluating the results for forming stage 2

Again you must evaluate the quality of the results as you did following the first forming stage to make certain that there are no severe dynamic effects to damage the analysis. We will not discuss the details of checking the results again because the procedures are the same as were used to check the results from the first forming stage. Some of the things to check are the histories of the kinetic energy, ALLKE, and the velocity of the reference node for die 2.

Die 2 moves as it is pushed by the blank, which is pushed by punch 2. Since the bodies may not be exactly in contact at the start of the step, some impact may occur as the bodies interact. When the blank impacts die 2, even with a small velocity, die 2 will oscillate somewhat since it sits on a spring and dashpot. Although it is best to avoid these oscillations as much as possible, they have little effect on the solution because the predominant forming is occurring in the dome region. The deformed model following the second forming stage is shown in Figure 7–31.

Continue with another springback analysis in ABAQUS/Standard. Perform the springback analysis in ABAQUS/Standard just as you did the first springback analysis. In fact, you must only change the *IMPORT option block to the following:

*IMPORT, STATE=YES, UPDATE=NO BLANK,

Save the springback input in a file called draw_spring2_std.inp, and run the springback analysis using the following command:

abaqus job=draw_spring2_std oldjob=draw_stage2

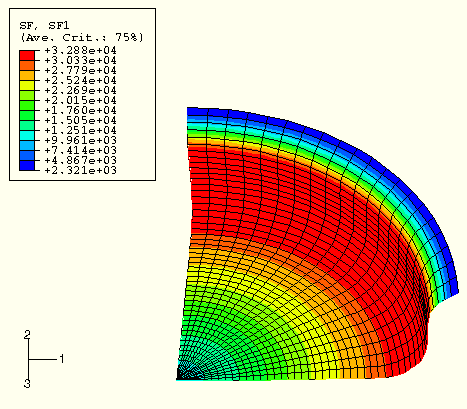

Figure 7–32 shows a contour plot of SF1 following the final springback in ABAQUS/Standard.

Figure 7–32 Contour plot of SF1 following final springback in ABAQUS/Standard (swept model for visualization purposes only).