Products: ABAQUS/Standard ABAQUS/Explicit

This problem illustrates the use of the smeared crack model in ABAQUS/Standard and the brittle cracking model in ABAQUS/Explicit for the modeling of reinforced concrete, including cracking of the concrete, rebar/concrete interaction using the “tension stiffening” concept, and rebar yield. The structure modeled is a simply supported slab, reinforced in one direction only. The slab is subjected to four-point bending. The local energy release and the concrete-rebar interaction that occur as the concrete begins to crack are of major importance in determining the structure's response between its initial, recoverable deformation and its collapse. The problem is based on an experiment by Jain and Kennedy (1974) and has been analyzed numerically by others (Gilbert and Warner, 1978, and Crisfield, 1982).

The dimensions of the slab and the layout of the reinforcements are shown in Figure 3.2.3–1. The symmetry of the problem suggests that only half the slab needs to be modeled.

We assume that the response is essentially one-dimensional but model the slab in ABAQUS/Standard as a beam, as a shell, as a continuum, and as a continuum shell to provide verification of the reinforced-concrete modeling capabilities. The response will be uniform in the central section of the slab, so a simple mesh will suffice. The beam and shell models use five elements in the half-slab. The number of concrete integration points through the thickness of the slab is set to nine instead of the default of five points. This provides a smoother response as the cracks propagate through the thickness.

The solid element models use second-order elements or reduced-integration linear elements, because this is a bending problem and the first-order fully integrated elements do a poor job of modeling bending. Two second-order elements are used through the thickness of the slab so there will be enough stress calculation points through the thickness for the response to be reasonably smooth (as in the beam and shell models). Five elements are again used along the half-slab. Because bending is the primary mode of deformation, a minimum of four reduced-integration linear elements (C3D8R or CPS4R) are needed through the thickness of the model to capture the response adequately. Four different CPS4R meshes are used to assess the sensitivity of the results to mesh refinement: a 4 × 10 mesh, a 4 × 20 mesh, an 8 × 10 mesh, and a 4 × 40 mesh.

The material properties are taken from Gilbert and Warner (1978) and are shown in Table 3.2.3–1. The concrete cracking model in ABAQUS/Explicit allows unlimited strength in compression. This is a reasonable assumption in this problem, because the behavior of the structure is dominated by cracking due to tension in the slab under bending.

The effects of the concrete rebar interaction and the energy release during cracking are modeled indirectly in ABAQUS by adding tension stiffening to the plain concrete model, as illustrated in Figure 3.2.3–2. This approach is described in detail in “An inelastic constitutive model for concrete,” Section 4.5.1 of the ABAQUS Theory Manual, and “Concrete smeared cracking,” Section 11.5.1 of the ABAQUS Analysis User's Manual, for ABAQUS/Standard; and in “A cracking model for concrete and other brittle materials,” Section 4.5.3 of the ABAQUS Theory Manual, and “Cracking model for concrete,” Section 11.5.2 of the ABAQUS Analysis User's Manual, for ABAQUS/Explicit. The simplest tension stiffening model, a linear reduction in the tensile strength beyond cracking failure of the concrete, is used in this problem, following Crisfield (1982). To illustrate the effect of tension stiffening parameters on the explicit dynamic response, three different values (5 × 10–4, 8 × 10–4, and 11 × 10–4) are used in the ABAQUS/Explicit analysis for the strain beyond failure at which all the tensile strength of the concrete is lost. The ABAQUS/Standard analysis uses a value of 5.7 × 10–4 (about 10 times the failure strain), a typical assumption for standard reinforced-concrete designs that gives a reasonable match to the experimentally measured response of the slab. For illustration purposes the ABAQUS/Standard analyses are also run without tension stiffening effects, although this is not recommended as a model for practical cases.

Since the explicit dynamic problem involves pure bending, the response is controlled by the material behavior normal to the crack planes. The material's shear behavior in the plane of the cracks is not important. Thus, the choice of shear retention in ABAQUS/Explicit has a minimal influence on the results, provided that a reasonable value is used. We have chosen to use a shear retention that is exhausted at a value of crack opening that is 100 times the value at which the tension stiffening is exhausted.

Reinforced concrete solutions involve regimes where the load-displacement response is unstable. The Riks procedure in ABAQUS/Standard, described in “Modified Riks algorithm,” Section 2.3.2 of the ABAQUS Theory Manual, is designed to overcome difficulties associated with obtaining solutions during unstable phases of the response. It assumes proportional loading and develops the solution by stepping along the load-displacement equilibrium line with the load magnitude included as an unknown. When the Riks method is used, the relative magnitudes of the various loads given on the data lines specify the loading pattern. The actual magnitudes are computed as part of the solution. The user must prescribe loads and provide solution parameters that will give a reasonable estimate of the initial increment of load. If the response is linear, this first increment of load will be the ratio of the initial time increment to the time period, multiplied by the actual load magnitude. If the response is nonlinear, the initial load increment will be somewhat different, depending on the degree of nonlinearity. The termination condition for the analysis is set in this case by specifying a maximum required displacement in the middle of the step as 9 mm (.35 in). This is enough to ensure that a limit condition is reached.

Since ABAQUS/Explicit is a dynamic analysis program and in this case we are interested in a static solution, care must be taken that the slab is loaded such that significant inertia effects are avoided. For analyses such as this one, in which the static load-displacement response is unstable, it may be difficult to avoid inertia effects with a dynamic procedure if force-controlled loading is used (even if the forces are ramped on slowly). Displacement-controlled loading is often a viable alternative. In this problem the slab is loaded by applying a velocity that increases linearly from 0.0 to 5.0 in/second over 0.1 seconds. This loading causes a midspan deflection of approximately 0.3 in. The loading is slow enough to ensure that quasi-static solutions are obtained.

The boundary conditions are symmetric about ![]() (all nodes along

(all nodes along ![]() have

have ![]() prescribed) and, for the C3D8R models, symmetric about

prescribed) and, for the C3D8R models, symmetric about ![]() –1.5 in (all nodes along

–1.5 in (all nodes along ![]() –1.5 in have

–1.5 in have ![]() prescribed). All the nodes along the bottom edge (

prescribed). All the nodes along the bottom edge (![]() –0.75 in) at

–0.75 in) at ![]() 15 in are given the condition that

15 in are given the condition that ![]() .

.

Results for all analyses are discussed in the following sections.

The ABAQUS/Standard analyses are compared with the experimental response on the basis of the deflection at the middle of the slab plotted versus the moment per unit width on that section of the slab. Figure 3.2.3–3 shows the analyses that do not include tension stiffening, and Figure 3.2.3–4 shows those that do include tension stiffening in the manner described above for the beam, shell, and continuum models. The experimental data obtained by Jain and Kennedy (1974) are also plotted on these figures. In the analysis without tension stiffening the initial cracking of the concrete causes a loss of strength in the slab, while the inclusion of tension stiffening eliminates this drop in load even though the concrete is cracking. The cracks propagate rapidly through the slab, until collapse occurs as the rebar yields. The collapse load is well predicted by all the models, and the various geometric models are reasonably consistent both with and without tension stiffening. The improvement in predicting the actual response obtained from including tension stiffening is obvious when the two figures are compared, graphically illustrating the need for including this effect in the model.

The results for the continuum shell element analysis are similar to results obtained from the S8R model.

Figure 3.2.3–5 shows the 4 × 20 mesh that was used in the ABAQUS/Explicit analysis. Figure 3.2.3–6 shows the deformed shape at ![]() 0.1, which is the point of full load application.

0.1, which is the point of full load application.

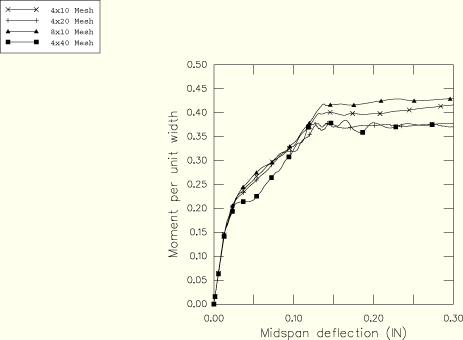

The load-deflection response of the slab for the four different mesh densities using a tension stiffening value of 8 × 10–4 and CPS4R elements is shown in Figure 3.2.3–7. Meshes with 10 elements along the length predict a slightly higher limit load than the mesh with 20 elements along the length. The mesh with 40 elements along the length of the slab gives results that are nearly identical to those given by the mesh with 20 elements. The tension stiffening study described next is, therefore, performed using the 4 × 20 mesh.

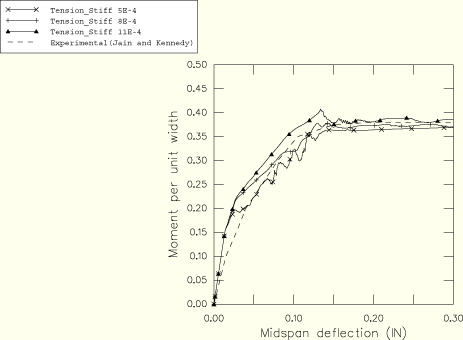

The results using the 4 × 20 mesh of CPS4R elements are compared to the experimental data in Figure 3.2.3–8 for three different values of tension stiffening. It is clear that the less tension stiffening used, the softer the load-deflection response will be during the cracking of the concrete. The middle value of tension stiffening appears to match the experimental data best. The load-deflection responses during the latter part of the analyses are almost entirely governed by the yield in the rebar and are, therefore, nearly independent of the tension stiffening.

The results using the 4 × 20 mesh of C3D8R elements with the various values of tension stiffening are compared with the experimental data in Figure 3.2.3–9. The results using a 2 × 10 mesh of S4R elements with the various values of tension stiffening are compared with the experimental data in Figure 3.2.3–10. The results for both C3D8R and S4R elements are similar to those obtained with the CPS4R elements.

Slab modeled as a beam with tension stiffening.

Slab modeled with shell elements of type S8R with tension stiffening.

Slab using element type CPS8 (plane stress) with tension stiffening.

Slab using element type CPE8 (plane strain) with tension stiffening.

Slab using element type C3D20 with tension stiffening.

Slab modeled with shell elements of type SC8R without tension stiffening.

Slab modeled with 40 CPS4R elements (4 × 10 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 8.0 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 80 CPS4R elements (4 × 20 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 8 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 80 CPS4R elements (8 × 10 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 8 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 80 CPS4R elements (4 × 20 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 5 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 80 CPS4R elements (4 × 20 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 11 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 80 C3D8R elements (4 × 20 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 5 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 80 C3D8R elements (4 × 20 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 8 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 80 C3D8R elements (4 × 20 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 11 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 160 CPS4R elements (4 × 40 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 8 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 20 S4R elements (2 × 10 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 5 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 20 S4R elements (2 × 10 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 8 × 10–4.

Slab modeled with 20 S4R elements (2 × 10 mesh) using a tension stiffening value of 11 × 10–4.

Crisfield, M. A., “Variable Step-Lengths for Nonlinear Structural Analysis,” Report 1049, Transport and Road Research Lab, Crowthorne, England, 1982.

Gilbert, R. J., and R. F. Warner, “Tension Stiffening in Reinforced Concrete Slabs,” Journal of Structural Division, American Society of Civil Engineering, vol. 104, ST12, pp. 1885–1900, 1978.

Jain, S. C., and J. B. Kennedy, “Yield Criterion for Reinforced Concrete Slabs,” Journal of Structural Division, American Society of Civil Engineering, vol. 100, ST3, pp. 631–644, 1974.

Table 3.2.3–1 Assumed material properties for one-way slab. Reinforcement ratio (volume of steel: volume of concrete) 7.2 × 10–3.

| Concrete properties | |

| Young's modulus: | 29 GPa (4.2 × 106 lb/in2) |

| Poisson's ratio: | 0.18 |

| Yield stress: | 18.4 MPa (2670 lb/in2) |

| Failure stress: | 32 MPa (4640 lb/in2) |

| Plastic strain at failure: | 1.3 × 10–3 |

| Ratio of uniaxial tensile to compressive failure stress: | 6.25 × 10–2 |

| Density: | 2400 kg/m3 (2.246 × 10–4 lbf s2/in4) |

| Cracking failure stress: | 2 MPa (290 lb/in2) |

| In the ABAQUS/Explicit analyses “tension stiffening” is assumed as a linear decrease of the stress to zero stress at a direct cracking strain of 5 × 10–4, 8 × 10–4, or 11 × 10–4. | |

| Steel (rebar) properties | |

| Young's modulus: | 200 GPa (29 × 106 lb/in2) |

| Yield stress: | 220 MPa (31900 lb/in2) (Perfectly plastic) |

Figure 3.2.3–7 Moment-deflection response of Jain and Kennedy slab; influence of mesh refinement. CPS4R elements (ABAQUS/Explicit).

Figure 3.2.3–8 Moment-deflection response of Jain and Kennedy slab; influence of tension stiffening on 4 × 20 mesh. CPS4R elements (ABAQUS/Explicit).