| Raymond Smothers, r.d.smothers@wustl.edu (A paper written under the guidance of Prof. Raj Jain) |

Download |

| Raymond Smothers, r.d.smothers@wustl.edu (A paper written under the guidance of Prof. Raj Jain) |

Download |

Wi-Fi sensing is an emerging technology that leverages Wi-Fi signals to detect movement, individuals, and more within a given environment. This has a wide range of applications including in healthcare, agriculture, and enabling IoT applications. In order to cover a wide variety of applications, the IEEE 802.11bf task group was formed in an effort to develop a sensing protocol to be used within wireless local area networks. In this paper we will discuss the WLAN sensing protocol proposed by the IEEE 802.11bf task group and some of its key features. As a protocol that looks to standardize the emerging Wi-Fi sensing technology, we will also give some background on the details related to Wi-Fi sensing systems and some of the applications where research is being done to apply these systems.

WLAN Sensing, Wi-Fi Sensing, IEEE 802.11bf, Wireless Communication, Received Signal Strength Indication (RSSI), Channel State Information (CSI)

Wi-Fi sensing is an emerging technology that has garnered a large amount of attention in recent years. Wi-Fi sensing is a method of utilizing Wi-Fi signals to detect movement within a given environment. There are already a variety of proposals and areas of focus for applications leveraging the unique capabilities of Wi-Fi sensing including healthcare and agriculture just to name a few.

The IEEE 802.11bf task group was formed to establish a standard protocol for Wi-Fi sensing that can be utilized in wireless local area networks (WLANs). This WLAN sensing protocol aims to provide coverage for the variety of applications currently being researched and proposed.

In this paper, I aim to provide a survey of Wi-Fi sensing and applications that utilize Wi-Fi sensing that are being researched or developed. In addition, I will provide an overview of the WLAN sensing protocol being developed as well as challenges and future growth opportunities that future works will need to address.

In this section we will give a primer over Wi-Fi sensing including a high-level functional overview of how Wi-Fi Sensing functions, the architecture behind many of the devices present in the market currently, and some of the popular applications and uses for Wi-Fi Sensing devices.

Wi-Fi sensing as a concept is relatively new and proposes to use Wi-Fi radios as sensors by measuring the variations in the wireless channel to track people in a given environment [Khalili20]. Early Wi-Fi systems used received signal strength (RSS) in sensing environmental changes, but popularity in Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) technology allowed for finer-grained channel responses called channel state information (CSI). See section 3.6 for more information.

In an indoor environment in particular, a Wi-Fi signal will undergo multipath propagation. The corresponding frequency response that is received can be measured by using the Wi-Fi network interface controller's CSI, a sample of the channel response which includes phase and amplitude information [Tan22].

Any motion in a Wi-Fi enabled area will influence the signal propagation, meaning that by the time a device receives that signal there will be variation in the amplitude [Tan22]. Phase can be used to measure relative distance and direction of the Wi-Fi signal propagation, and in conjunction with amplitude changes, can depict signal changes and corresponding motion.

Each network can consist of different numbers of devices with a variety of capabilities. As a result, different architectures have been defined which majority of sensing environments can be categorized into.

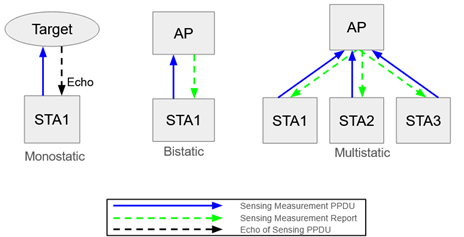

Each Wi-Fi system is unique, either by the configuration of the environment, devices, or a variety of other factors. Sensing architectures are used to categorize these complex and varying systems based on the number of sensing devices used in the system. The following are architectures are those supported by Wi-Fi systems are monostatic, bistatic, and multistatic.

Monostatic Sensing: This system consists of a single station (STA) and at least two antennas. The sensing measurement occurs in a manner like those of traditional radar systems by measuring the echoes of a transmission [Ropitault24], [Chen23].

Bistatic Sensing: This system consists of two STAs, a sensing transmitter and a sensing receiver. Typically, one STA acts as the access point (AP) while the other acts as the client STA. The sensing receiver is responsible for taking measurements from the transmitted physical layer protocol data units (PPDUs) transmitted by the sensing transmitter by extracting information from either the received signal strength or by using the subcarriers in an OFDM system [Ropitault24], [Chen23]. For more information regarding sensing measurements see section 3.6.

Multistatic Sensing: This system is an extension of the Bistatic sensing architecture, such that it consists of the same two types of devices, those being sensing transmitters and sensing receivers, but this architecture has more than one transmitter or receiver. This is typically done by having multiple STAs and a single AP. This type of sensing system can obtain measurements by measuring the signals sent by multiple STAs, or by having multiple signals measured by multiple STAs [Ropitault24], [Chen23].

Figure 1: Diagram of PPDU behavior in different WLAN sensing architectures [Chen23].

Most applications fall into one or more of these architectures, and as such we will look at a few of these applications that Wi-Fi sensing is either being proposed for potential use or is currently being used in.

Research into applications for Wi-Fi sensing are numerous as there is no shortage of areas that benefit from having a sensorless monitoring method, several specific areas have become popular areas of study including health monitoring, human monitoring, and agriculture.

The current state of monitoring systems can be divided into two separate systems: Contact-based systems and contactless systems [Ge23]. Contact-based systems involve wearable devices that are required to be on or near an individual to capture health information, while contactless systems leverage a network of camera-based systems and devices to track and monitor individuals and have proven to be highly accurate like in the case of detecting seizures where the accuracy is as high as 95% [Ge23], [Korany22].

Wearable health monitoring devices are readily available in many countries; however, these devices are expensive, and the accuracy of these devices can be unreliable in cases such as those suffering from chronic seizures with detection accuracy being as low as 89.7% [Korany22]. In cases in which one is dealing with children or mentally disabled individuals, they may be averse to have a physical device on or near their body, and in cases with elderly patients at risk of falling these devices may either be damaged or broken [Khalili20], [Korany22].

Contactless systems have their limitations as well. Systems relying on visual systems alone cannot represent complicated health conditions, and in the case of patients suffering from high rates of false alarms, in one study they found that the rate of false alarms in patients suffering from seizures was 0.78 instances per night [Korany22]. In addition, video-based solutions require constant monitoring of patients which is not always feasible such as in low-light environments, and such monitoring activities can violate patient privacy [Khalili20], [Korany22].

Currently both systems have advantages for patients and workers in the healthcare industry, but neither are perfect. With the addition of Wi-Fi sensing officials are hoping to leverage the non-line-of-sight aspect of it while reducing the reliance of expensive video-based systems and contact-based wearables. In [Korany22] researchers proposed a system that has a low rate of false alarms and an accuracy of 93.85% when detecting seizure instances [Korany22]. Another study proposed a fall detection system to be used with elderly people and found that precision was comparable to contact-based systems with an 87% detection rate and about an 18% false alarm rate [Khalili20].

Human monitoring, in this instance, is leveraging Wi-Fi sensing to monitor individuals in a given environment and recognize specific individuals, outliers such as intruders, or specific actions an individual can take. A popular focus of research is to use Wi-Fi sensing for gesture recognition which is when an individual performs a specific action or series of actions to affect an application or device. This is one of the key enablers of smart homes, and several studies have proposed systems using Wi-Fi sensing in order to get specific responses such as a study where one such system, WiG, which was able to average 92% in an environment with line of sight and 88% in a non-line of sight environment [He20]. Gesture recognition is not the only form of monitoring researchers have been looking at.

Other areas of human monitoring involve determining whether a human is in an area of interest, which can be used to detect intrusions by unwanted individuals as well as tracking the number of people in large groups or crowds [Khalili20], [He20].

When it comes to agriculture, maintaining crop stores is necessary for many reasons including food demand and shortages due to natural disasters. Often these stores require specific environments to maintain food quality. One such example of this is grains, where temperature and moisture must be monitored, and determining moisture levels in grains can be time consuming, complex, and in some cases expensive [Yang23]. A study proposed a design for a system called Wi-Wheat+ that will utilize CSI data from Wi-Fi sensing and mathematical models to determine moisture levels in grain stores [Yang23].

With a wide range of applications that must be covered under Wi-Fi sensing technology, it is no surprise that there has been a demand for a standard protocol to be developed for such devices. As such, the next section aims to present an overview of the work done by the IEEE 802.11bf task group who has proposed creating a Wi-Fi sensing protocol which would leverage Wi-Fi sensing within WLANs.

The 802.11bf task group was initiated in 2020 with the intent of developing a new amendment that aimed to support Wi-Fi sensing [Chen23]. The group aimed to support the WLAN sensing protocol in the sub-7 GHz band to support legacy standards such as 802.11ax and earlier standards, as well as the 60 GHz millimeter wave band to support new standards at millimeter wave frequencies such as 802.11ad/ay [Chen23], [14], [Restuccia21].

In the following section we will discuss device roles before going more in depth on the various phases a device must go through prior to performing sensing measurements, how the protocol works in both frequency bands, the different measurement instances, supported protocol bands, and finally a discussion on client-based sensing.

Prior to discussing the protocol, we will outline the different device roles and mechanisms to initiate sensing. The roles defined in the WLAN sensing protocol must consider devices that transmit the PPDUs for the sensing measurements and the receiver of these PPDUs that do the sensing measurements. In addition, we must consider Wi-Fi devices that function as the AP and devices that function as client STAs as well as various combinations based on the type of architecture [Ropitault24], [Chen23]. As such, the WLAN sensing procedure has four roles as outlined by 802.11bf:

Devices can have multiple roles depending on the number of Wi-Fi devices within a WLAN sensing system, for example in a Bistatic architecture, the sensing initiator and sensing receiver could be one device, while the other could take the roles of sensing responder and sensing transmitter.

Devices can have one or more roles, but that involves some coordination between all of the devices involved. As such, in the next section we will discuss the phases outlined in the WLAN sensing protocol that devices must go through in order to negotiate and setup proper roles in addition to performing the sensing measurements.

The WLAN sensing protocol as defined in 802.11bf is broken down into phases, where during each phase devices perform different functions based on the role they are given. The phases of the WLAN sensing protocol are sensing session setup, sensing measurement setup, sensing measurement instance, sensing setup termination, and sensing session termination [Ropitault24].

Sensing session setup: During this first phase, the sensing initiator and any sensing responders that are expected to participate in the sensing system must share their sensing capabilities and determine if each device can conduct sensing at all or if they support the WLAN protocol.

Sensing measurement setup: After each device communicates their capabilities to the group, the sensing devices configure themselves based on the sensing responder's capabilities and define operational parameters (OPs) to be used during the sensing process. Once completed, the sensing initiator will use its MAC address to assign a unique identifier that each device will use to reference the OPs decided upon.

Sensing measurement instance: Once OPs have been defined and the sensing measurement setup phase is complete, we can now perform sensing measurements. During this phase, sensing measurements are gathered by exchanging packets between the sensing initiator and sensing responder.

Sensing setup termination: When an application no longer needs sensing measurements, this phase is reached to terminate the measurement setup. There are two methods: explicit and implicit termination. Explicit setup termination can be initiated by either the sensing initiator or a sensing responder by sending a sensing measurement setup termination frame to the other devices in the system. Implicit setup termination occurs when a sensing measurement setup timer expires, signaling STAs to terminate the setup.

Sensing session termination: Often the final phase, this indicates to the STAs that are part of a sensing session to stop performing sensing measurements and to terminate the session.

Now that we have covered the different phases and what occurs during them, we need to look at the next section that outlines the different measurement instances outlined in the WLAN sensing protocol.

The WLAN sensing protocol outlines two distinct methods for networks to initiate a sensing measurement instance: Trigger-Based (TB) and Non-Trigger-Based (Non-TB). The following subsections will go into more detail as to how each method operates.

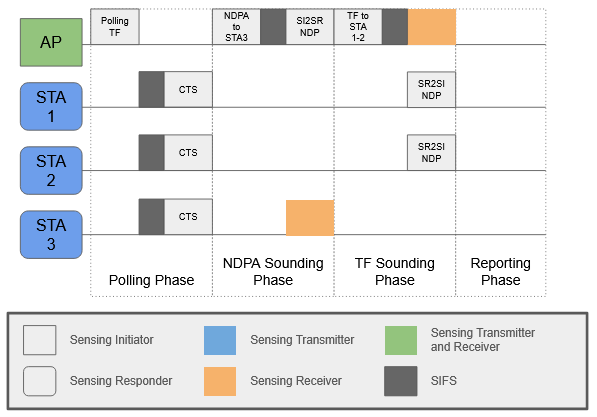

TB measurement instances require more than one sensing device, typically an AP and at least one client STA with the AP STA taking the role of the sensing initiator, and depending on the sensing architecture, will rely on one or more client STAs to take the role of sensing responders [Ropitault24], [Chen23].

The sensing initiator begins the process by polling the other STAs connected to the network, and if the client STA is able to participate in the sensing operation it will reply with a clear-to-send-to-self (CTS-TS) message [Chen23]. After receiving one or more CTS-TS messages, the AP will transmit a trigger frame (TF) or a null data packet announcement (NDPA) sounding to the client STAs that will begin the sensing measurement. Depending on the roles the STA devices negotiated in the setup phase and the direction of the network data being sent (uplink direction or downlink direction) will determine which message is transmitted.

Figure 2: Diagram of procedure for Trigger Based measurement instance [Ropitault24].

Now that we have covered details regarding TB measurement instances, we will now go into Non-TB measurement instances.

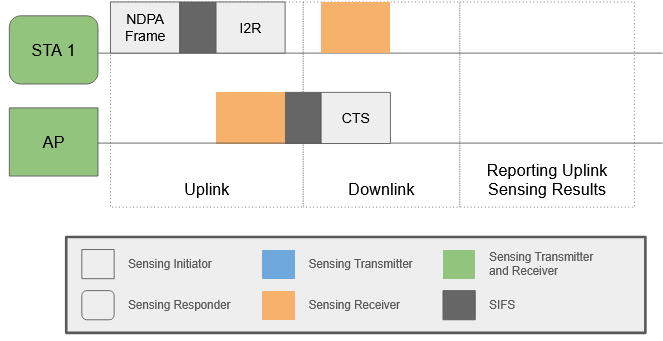

Non-TB measurement instances occur when a client STA initiates a sensing measurement with at least one other STA as the sensing responder [Ropitault24], [Chen23]. Non-AP STAs are limited such that they cannot support multiple responses, so the client STA initiating the sensing measurement will send a NDPA to the AP followed by an Initiator-to-Responder (I2R) request. With this, the AP will function as a coordinator for the request and since an AP does not typically rely on power saving modes the client STA initiating the request can skip the polling phase of the sensing measurement like in the TB measurement instance.

Figure 3: Diagram of procedure for Non-TB measurement instance [Ropitault24].

With some of the background established, we will now look at how the WLAN sensing protocol behaves in the different bands.

The 802.11bf task group set out to develop the WLAN sensing protocol aimed to support as many devices and applications as possible, and therefore set out to support both legacy and more recent frequency bands. We will first discuss how the protocol works with frequency bands below 7 GHz and then move into the 60 GHz millimeter wave frequency band.

In an effort to support legacy standards such as 802.11ax and earlier, the 802.11bf task group aimed to have support in frequency bands below 7 GHz [Restuccia21]. That said, there are advantages for supporting this frequency band outside of legacy support for older standards such as CSI measurements in this frequency providing information on movements that are relatively large in addition to signals being able to better propagate through walls [Restuccia21].

WLAN sensing in frequencies below 7 GHz build on top of existing beamforming sounding sequences. Reusing the null data packets (NDPs) allows WLAN sensing to benefit from the fact that most devices implement the 802.11 protocols. In addition, NDPs lack any payload field unnecessary in Wi-Fi sensing applications and have the training fields that are required as part of the sensing protocol [Chen23]. The WLAN sensing protocol covers bistatic and multistatic systems in the sub-7 GHz, but not monostatic.

Next, we will look at how the WLAN protocol applies to the 60 GHz millimeter wave band.

The WLAN sensing protocol in 60 GHz millimeter wave band is built on existing standards that define directional multi-gigabit (DMG) and enhanced DMG (EDMG) communications with modifications to satisfy sensing requirements. Like how NDPs were able to be adapted for sensing applications in sub-7 GHz bands, the same is similar with DMG and EDMG PPDUs, as the preamble and training fields can be used for sensing measurements. Unlike sub-7 GHz bands, all sensing architectures (monostatic, bistatic, and multistatic) are considered viable in the 60 GHz band [Ropitault24].

There are instances where clients have limited capability to get sensing measurement information and just like with the frequency bands, the WLAN protocol outlines new features to alleviate those limitations.

The WLAN protocol has a wide range of applications, and supporting multiple frequency bands enables industries to leverage this protocol for a variety of devices. The next section we will look at is one of the biggest components to the WLAN sensing protocol, client-based sensing.

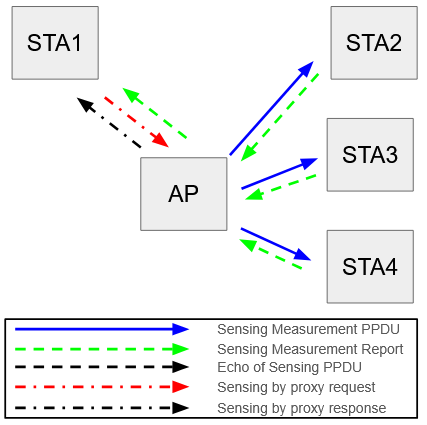

Wi-Fi sensing systems on the market consist mostly of multistatic devices that rely on APs to obtain sensing measurement data [Ropitault24]. As a result, the 802.11bf task group has outlined the following features that should enable client STAs to perform multistatic sensing.

Normally a client must go through an association process prior to exchanging information with an AP and information can only be exchanged by devices that are associated with one another. A limitation exists in situations where a client wants to receive packets from multiple APs, and as such the 802.11az task group defined a procedure called Pre-Association Security Negotiation (PASN) that the 802.11bf built on by extended the set of frames exchanged in order to enable clients to perform multistatic sensing in an environment with more than one AP [Ropitault24].

Client STAs are often limited and provide diminished capabilities when directly compared to an AP STA, therefore the 802.11bf task group wants to leverage the capabilities by allowing APs to function as proxies for client devices.

Sensing by Proxy (SBP) enables client STAs to collect more sensing measurement information by way of leveraging the capabilities of APs such as increased power availability and more range. An AP will function as a proxy at the request of a client STA to perform a sensing measurement and report the obtained information back to the client STA [Ropitault24].

Figure 4: Diagram of client STA initiating sensing by proxy [Chen23].

There are situations where client STAs might be better able to get the sensing information that they need from other client STAs rather than an AP. This feature of the WLAN protocol does not enable clients to directly transfer data from one client to another so the procedure for client-to-client sensing is managed by an AP which is sent a request from one client which can specify one or more other clients it wishes to leverage [Ropitault24].

Prior to the WLAN sensing protocol, there were two primary types of reporting information measured by the sensing devices: RSS or Received Signal Strength Indication (RSSI) and CSI.

RSS or RSSI were used for early indoor Wi-Fi sensing systems. Wi-Fi signals are easily interfered with during propagation by the environment. As a result of such interference, when the signal is received the resulting difference in the expected signal strength compared to the strength of the signal received will result in RSSI [Yu22], [Wang21].

By using statistical models RSSI data can be used for detecting positions and movement of individuals in an environment. Another benefit of RSSI is that there are no special hardware requirements that are needed for the receiving device to utilize such capabilities [Lin20]. The limitation is that RSSI is not as detailed as is needed in some applications, leading to a range resolution that suffers from coarse grained information [Ropitault24], [Yu22], [Lin20]. The 802.11bf task group does not support RSSI in the WLAN sensing protocol, and instead uses CSI which is much more detailed [Ropitault24].

CSI utilizes OFDM and multiple-input and multiple-output (MIMO) technology by determining how Wi-Fi signals propagate [Ma20]. This is done by feeding data extracted from subcarriers and analyzing how the amplitude and phase were impacted during propagation [Tan22], [Ma20]. Since the range resolution of CSI data is more detailed, this allows it to be used in a wider range of applications. The only issue with CSI reporting data is that not all network interface cards (NICs) provide CSI data and require modifications to the device drivers or the use of software-defined radios (SDRs) [Shao22].

At present there are advantages and disadvantages to using either RSSI or CSI in order to obtain positional information in a Wi-Fi sensing environment. With regards to accuracy and range, the benefits of CSI are just too great even considering the ability to use RSSI on most devices [Shao22]. This is just one example of the challenges still facing Wi-Fi sensing systems that we will continue looking at in the next section.

The WLAN protocol will enable the growth of both applications and research into the area of Wi-Fi sensing, however, being a relatively new field there are still several challenges and growth opportunities that will need to be addressed including response resolution, cooperation between sensing and communication, and reliability.

Many of the applications discussed in this paper are limited to a small area, typically a single room or office WLAN sensing has a limited range depending on the environment, somewhere between 0.5 m to 10 m [Ropitault24]. When applied to larger or more complex areas, the results vary greatly and are typically less accurate overall, limiting it to applications that use lower resolution [Ropitault24], [Tan22]. In addition to the range, there is a struggle with complexity in sensing areas.

As an environment gets more complex and variability in the environment increases, the accuracy of such systems is inversely affected. Many works rely on consistent environments where furniture and objects do not move, and subjects are of similar stature [Tan22]. This puts into question the viability of some systems when introduced to more realistic environments where things can change at regular intervals. In addition, sense Wi-Fi sensing is used to detect movement based on the interruption of Wi-Fi signals, movement becomes the limiting factor, and a certain amount of motion must occur before such information will appear within the sensing measurements, otherwise it will simply look as though the environment is normal.

The primary purpose of Wi-Fi continues to be to transmit data, while applications such as Wi-Fi sensing are secondary for most individuals and groups. Wi-Fi sensing systems are reliant on a consistent stream of sensing measurements to maintain a high level of accuracy [Ropitault24]. This leads to the discussion of how to balance the demands of Wi-Fi sensing and Wi-Fi communication so that both demands are satisfied such that Wi-Fi sensing is provided with the regular interval of sensing measurements so that it can maintain accuracy and the Wi-Fi communication remains uninterrupted.

Most works consider only one or two individuals during testing. It is possible to track multiple individuals within the same environment, however, the transmission rate required to do so increases per user, affecting Wi-Fi communication as a result [Tan22]. In addition, as the number of users increases the tracking accuracy of each individual decreases, which severely limits the applications that support more than one or two users [Tan22].

In this paper, we discussed what Wi-Fi sensing is and how those in various areas of study are looking to leverage this emerging technology and its capabilities to assist in the lives of individuals and industries. Wi-Fi sensing has been advancing for several years, and now with the help of the IEEE 802.11bf task group and their efforts in defining the WLAN sensing protocol researchers and industry leaders will be able to solve the challenges and push the technology further. The WLAN sensing protocol will support range resolution through sensing measurements obtained through CSI and further client-based sensing and support for legacy and modern IEEE 802.11 amendments to enable wider range of IoT applications.