A Survey of 6G Technical Requirements, Architecture, and Use Cases

| Andrew Carpenter, a.d.carpenter@wustl.edu (A paper written under the guidance of Prof. Raj Jain) |

Download |

Abstract

The next generation of wireless networks, 6G, aims to address increasing connectivity and bandwidth demands driven by applications in IoT, haptic technologies including cyberspace, popular high-fidelity video devices, mobile and autonomous vehicle networks, and more. 6G builds off the existing 5G standard to improve user-experienced data rates, extreme hotspot connectivity, increased efficiency, and improved utilization of the electromagnetic spectrum up to THz frequencies. Advancements in blockchain technology, AI, and ML will drive key security and efficiency optimizations planned for 6G and research is underway for new PHY layer modulation and coding techniques to support the expected capabilities of 6G networks.

Keywords

Artificial Intelligence, Beamforming, Blockchain, Channel Estimation, Cyberspace, Holographic Communication, Internet of Things, Machine Learning, Metaverse, Mobile Networks, Modulation, Spectrum Allocation, Swarm Intelligence, THz Band, Vehicular Networks

Table of Contents

6G Motivation and Use Cases

During the COVID-19 pandemic the world was able to move many social and business interactions to the virtual world with high-speed video and audio, a transition that is exemplary of the current need for high-speed wireless networks. 5G meets this existing need, enabling remote jobs, virtual education, and entertainment with high-fidelity video streaming. As the world's technological needs grow, the need for looking for the next generation of wireless networks grows too, leading to the need for beyond 5G. This survey will cover the research for beyond 5G, specifically IMT-2030 or 6G, the next standard of wireless networks. First, we will discuss the motivation for 6G, including specific use cases that push the requirements of wireless networks and demand growth. We will then cover the technical requirements of both the 6G wireless spectrum, physical infrastructure, and security, and conclude with the many architectural changes between 5G and 6G networks.

Mobile Networks

The increasing demand and availability of high-fidelity video, made possible by increasingly accessible mobile devices capable of 4K video, pushes the limits of existing 5G networks. For example, 4K video requires a user data rate of 15.4 Mb/s [1] which is below user-experienced data rate of 100 Mb/s [2] but as availability of 4K mobile devices increases so too does the demand on the network.

Beyond the demand for 4K video on mobile devices, the sheer number of mobile devices requiring connectivity shows a trend towards needing beyond 5G. The IMT-2020 specification provides 106 devices per km2 with an area traffic of 10 Mb/s/m2 [2] which limits the ability of 5G to enable extreme hotspots of user traffic. 6G would extend this significantly to allow for the growing number of mobile devices demanding high-speed wireless network connectivity.

Blockchain & Security

As the world becomes increasingly technologically adept, the risk associated with security and privacy increases as well. When considering the next generation of wireless networks, security is an essential factor to improve upon, and the prevalence of blockchain technology provides an avenue for implementation [3]. Blockchain works by creating a series of digitally signed 'blocks' which form a chain where each block provides proof of a timestamped transaction, signed by the private key associated with the previous block (often the previous owner of a cryptocurrency) and including the hash of the chain. This means that transactions in the chain cannot be altered as the history in the chain must match the hash. Blockchain 3.0 provides non-cryptocurrency applications which drives its inclusion in the next generation of wireless networks [11]. Given the rise in popularity and demonstrated security of blockchain, work can begin on 6G security, in figuring out how to leverage the peer-to-peer trust system for future 6G networks, especially IoT systems [14].

Cyberspace

The data rates currently supported by 5G enable the video/audio traffic currently demanded by the average consumer today, but there is an observable trend towards needing beyond 5G when it comes to cyberspace and other forms of data-transmission with 6 degrees of freedom (6DoF).

Cyberspace in short is a 3D rendering of a virtual space for a user to interact with. This includes the Metaverse, a virtual reality space where the user experiences virtual 6DoF video and audio through a virtual reality headset, as well as holographic communication, a technology that is trending and will require massively higher data rates than are supported by 5G, potentially up to 4.32 Tb/s [1] for volumetric holographic renderings of a person.

Other more general technologies comprise cyberspace, including 6DoF sensing, spatial audio with 6DoF [5], or transmissions which incorporate more of the five senses. All these technologies require higher data rates than are supported by 5G and represent the trending demands of existing wireless networks.

AI and Machine Learning

Both AI and machine learning have huge potential to expand the capabilities of beyond 5G networks. The first major case is the application of machine learning to modulation and coding, specifically when digitizing a received signal. Especially in the THz band, interference and general loss of signal is a big issue, and being able to decode a noisy/lossy signal is the key to solving this challenge. This application of machine learning will enable processing the shorter symbol duration and shorter code words that will be used in the THz band [1].

A prominent application of AI in modern networks has been through the use of Swarm Intelligence (SI) which defines the intelligence shared by a collection of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Another proposed application in the form of a 'Deer Hunter' algorithm is advanced spectrum sensing, by which AI would be used to increase efficiency and security of spectrum sensing for mobile nodes, including a more intelligent system for detecting malicious nodes and creating null zones [13]. A different possible use case for AI is within routing protocols, where it has already been used in underwater-sensing networks to provide energy-efficient routing. Cognitive radio and software-defined networking are other areas where supervised machine learning as shown significant benefits, and more generally any application which has a lot of training data and experiences challenges due to environmental factors can be improved significantly through either AI or ML [10].

Vehicular Networks

The existing standard of Digital Short-Range Communication (DSRC) for vehicular networks cannot support the growing demand on vehicular-to-everything (V2X) communication from additional sensors in modern vehicles, both autonomous and manual. Even for non-autonomous vehicles, modern cars have sensors for light and range detection, infrared and video, as well as radar technology. There are strategies for reducing the data consumed from these sensors, including general data aggregation or more advanced machine learning techniques. However, given that the peak data rate demanded could reach up to 1 Gb/s [1], DSRC is already unable to support this with its peak data rate of 27 Mb/s, which may explain the lack of adoption leading to the reallocation of the spectrum. The mmWave band that 6G will offer would support these data rates, enabling both the growth in the number and precision of the sensors while also supporting existing systems which do not aggregate the data. This band would not however solve the current challenge of beamforming in V2X communications, where the high mobility and high frequency make it difficult to keep a beam properly aligned. Strategies for mitigating this issue, including active beam adjustment, still need to be researched [1].

On the lower end of the 6G spectrum, the sub-6 GHz band will provide V2X communications with a domain for reliable transmission. These transmissions will likely include broadcasts for non-critical information such as traffic control, positioning, weather, and other similar messages [1].

For autonomous vehicles specifically, 6G networks will enable the next generation of vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication, increasing safety, and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) enabling learning opportunities. The safety benefits include detailed awareness of vehicle positions relative to each other as well as information sharing, which can enable safer distancing between vehicles and overall safer execution of driving. The learning benefits come from the ability for road-side-units (RSUs) to receive private and anonymous data from autonomous vehicles which can improve the overall learning process for automated driving systems as well as improved mapping. This example of edge computation allows vehicles which may not have the necessary compute power, to utilize V2I communications to reinforce learning [14].

6G Technical Requirements

In order to make the case for a generational gap in wireless networks, 6G will need to utilize a new spectrum, both reusing existing sub-6 GHz spectrum and new THz spectrum. This will also require technical advancements in hardware to support the new THz spectrum.

Spectrum

Similar to previous generational improvements, 6G looks to make use of new spectrum, both to leave existing spectrum available for 4G and 5G but also to utilize sub-mmWave band and the advantages they offer. In this scenario, mmWave refers to the 0.1 THz to 10 THz frequency band, corresponding to 0.3 to 3 mm wavelengths [7]. There are 7 key bands of interest for 6G which are defined in Table 1. This spectrum ranges from 100 GHz to beyond 1 THz which allows for each window to meet a specific use-case. The loss of each window increases by 20 dB from 10 mm to 1 m and another 40 dB from 1 m to 100 m [1]. Window Band (GHz) Loss at 10 mm (dB)

| Window | Band (GHz) | Loss at 10 mm (dB) |

|---|---|---|

| W1 | 140-350 | 60.18 |

| W2 | 377-443 | 64.65 |

| W3 | 447-533 | 66.20 |

| W4 | 584-736 | 68.79 |

| W5 | 769-911 | 70.88 |

| W6 | 916-964 | 71.86 |

| W7 | 1001-1059 | 72.65 |

The first window, W1 also called the sub-THz band, is very promising given how much of the spectrum is currently unused, but some of it, specifically 141.8-275 GHz, is currently allocated for services like radio astronomy, various satellite systems, as well as some more traditional fixed and mobile services. These interstellar services pose a unique challenge when considering how to prevent interference, as it will be critical that interference not be directed upwards.

The only true THz window, W7, enabled significantly higher data rates but will be difficult to apply to many mobile use cases due to its short range and high sensitivity to directional alignment. Beamforming will be critical for utilizing this bandwidth, and techniques such as predictive beamforming may be employed to achieve success [1]. Channel estimation will be another issue with this new bandwidth, due in part to the increased number of antennas as well as shortened transmission intervals. Lastly, designing efficient hardware to perform signal processing and transmission is a key challenge of THz devices. While complex modulation techniques are not necessary above 1 THz to achieve Gb/s, even simple modulation techniques need to be integrated with efficiency in mind [15].

Infrastructure

Allocating the THz band and designing a system to use it is one challenge, but having the physical infrastructure to support it is another. With such a sensitive band, increasingly effective hardware will be required to support it. Already, existing 5G chips which process mm waves took years to be able to be integrated into mobile devices due to the complexity of reducing the chip size [9]. Work will need to be done to get new 6G chips with more complex modulation and security techniques reduced to the same size of existing chips, and the increased demand for small IoT devices means reducing the chip size even further is a priority.

In addition to decreasing the chip size, mobile devices will need to be able to make use of the multiple frequency windows offered by 6G which means the transceivers integrated into these devices will be required to support multiple bandwidths [8] and potentially multiple modulation and coding techniques. While the higher frequencies supported by 6G will make it easier to support more antennas in the same space, increasing the complexity and power of the transceivers will be a challenge.

Lastly, advancements in power need to be made in order to support 6G networks. As 6G works to support billions of autonomous IoT devices through energy-efficiency, these physical devices will still need to utilize improvements in battery life and efficient power delivery to succeed. Some techniques that will help facilitate this include wireless power transfer and wireless energy harvesting, which are different techniques that enable a standalone wireless device to receive power wirelessly [9].

Security

As we discussed earlier, advances in blockchain technology motivate a new generation of wireless networks which utilize this technology for security. Blockchain improve the security of the growing IoT portion of wireless networks, as it would remove the need for a centralized trusted entity to arbitrate communications between potentially untrusted parties [3]. The use of blockchain comes with additional challenges however. First is that blockchain fundamentally depends on the principle that there are more trusted computing entities than malicious ones, a principle that has so far enabled blockchain to succeed in cryptocurrency and beyond. In use with IoT however, it is conceivable that since the cost to produce such devices is minimal, a malicious entity could control a majority of participating computing devices which would break the security promises of blockchain. The other end of this spectrum is the potential for there to be a lack of participating devices, or a lack of devices with both compute power and low latency, meaning that depending on blockchain will introduce processing delays that would otherwise not be experienced with a known and computationally efficient trusted third-party [3]. For latency-sensitive devices such as medical sensors, this poses a significant issue and research must be done in order to address this challenge before relying on blockchain for 6G.

As body-area-networks (BANs) become more popular due to advances in medical/scientific technologies, security is an increasing concern and 6G will need to solve some of these concerns. For wearable sensors which communicate sensitive information, security needs to be a top priority for all participating devices. With decentralized cryptography, each device does not need to be capable of key generation or other more intensive cryptographic functions, but does need to be able to utilize some form of encryption and security. In addition to securing data transmitted, preventing the falsification of data, including impersonation of sensors, is critical. This applies also to devices outside of the scope of BANs, as location-based devices require security to prevent their identity being impersonated and the location/distance being falsified [15].

6G Architecture

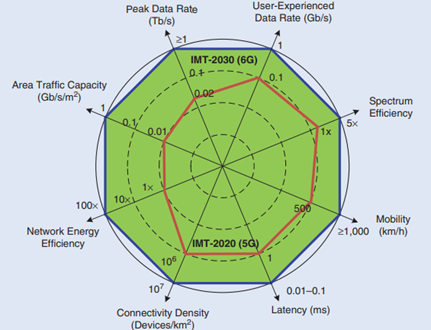

6G networks will bring with them massive design and structural changes compared to 5G which will result in significant performance improvements across the board. Figure 1 shows the key capabilities of 5G networks compared to the objectives of 6G networks.

Figure 1: IMT-2030 Key Capabilities of 6G Networks

[2]

Figure 1: IMT-2030 Key Capabilities of 6G Networks

[2]

These Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) include a peak data rate of up to 10 Tb/s for some THz applications, a user experienced data rate of 1 Gb/s and massively increased area traffic capacity by a factor of 100 [2]. One KPI not visualized is the inclusion of internet access on multiple moving platforms such as ships and planes, which will now be possible at speeds over 1,000 km/h [1]. These capabilities depend on the new PHY layer advances discussed next.

New Physical Layer

While OFDM has become massively popular with 4G and 5G, the drawbacks including spectral inefficiency due to subcarrier spacing and the cyclic prefix as well as frequency dispersion give motivation for finding other modulation techniques for 6G networks. There is not one specific modulation technique that has been chosen yet for 6G but several alternatives to OFDM are being considered.

One of the general categories of multiple-access techniques being considered is Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access (NOMA). All Orthogonal Multiple Access (OMA) techniques divide the domain into orthogonal blocks, for example OFDMA divides the frequency domain into orthogonal frequencies. NOMA works by dividing up the power domain into different power levels which are sent to multiple users. The user is then able to decode their signal depending on their measured Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), which at a very basic level means that depending on the power received the user would either decode the high-power signal as theirs, or decode the noise/interference as their signal [3]. Another orthogonal method that is being considered is Orthogonal Time-Frequency Space (OTFS) which divides the delay-Doppler domain, which is a sort of hybrid of the frequency and time domains, into blocks. OTFS is able to handle a wider range of frequencies from users with different power profiles much better than OFDM, but is still largely in the research phase.

Besides modulation techniques, improvements with coding are required for 6G to be able to meet the KPIs shown in Figure 1. Specifically for IoT devices that will make use of the higher frequencies offered by 6G, coding will both need to be short and low-power so that small, battery-powered devices can efficiently compute them, but these codes must also not be as error-prone as current short coding schemes currently are [1]. Coding is even more in the research phase than modulation and there are not currently any specific coding techniques chosen as frontrunners for 6G.

3.2 BeamformingBeamforming

As we move to higher frequencies, the antenna size and spacing both decrease, leading to different behaviors when beamforming. As well, beamforming is incredibly important for 6G as higher frequencies require more directional accuracy to avoid higher loss. One technique, called passive beamforming, utilizes phase shift adjustments via reconfigurable intelligent surfaces in addition to traditional active beamforming to increase the quality of the received signal. Similar to how active beamforming is divided into discrete sectors, there are a predetermined number of shifts available which means both techniques must be used in combination with each other [15]. Another beamforming technique that will be used is called dynamic beamforming or holographic beamforming and is a technique that 'steers' waves in a dynamic direction [3].

3.3 Channel EstimationChannel Estimation

Improved channel estimation will be a key change to the physical layer in 6G networks, with the move towards integrating AI. Traditionally channel estimation is determined in theory, and practical effects such as noise and interference can disrupt or cause inaccurate parameter estimation. Additionally, any non-linearity in the channel makes it even more difficult to estimate using traditional methods. 6G networks will rely on a deep-learning approach, where training data will be collected with known parameters and a model can be trained on the input data containing all the same noise and interference that a real system experiences. These models have shown to improve accuracy especially in non-linear systems, and are an overall less complex and more efficient alternative to traditional methods [10].

Multiple-Output (MIMO) systems

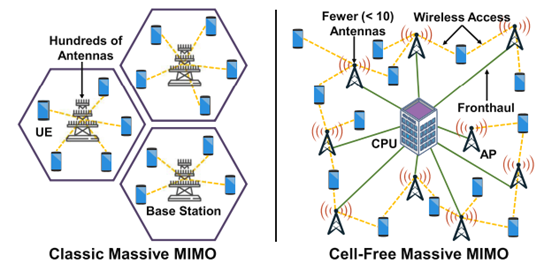

Multiple-Output (MIMO) systems are used effectively in current wireless networks and will be extended with 6G to include Ultramassive MIMO (U-MIMO) systems. This would be an order-of-magnitude increase in the number of antennas in a system, which will be combined with advances in beamforming to massively outperform existing 5G MIMO systems [1]. U-MIMO also enables better spatial diversity, which enables an overall more efficient system because less power is needed to reach users at different locations. One specific example of this is cell-free U-MIMO, which is a configuration that eliminates the challenge of transmitting to users on a cell-boundary.

Figure 2: Comparison of Classic MIMO versus Cell-Free MIMO

[10]

Figure 2: Comparison of Classic MIMO versus Cell-Free MIMO

[10]

Figure 2 shows the visual comparison between classic and cell-free MIMO. In cell-free MIMO each user device is able to connect to a subset of base-stations nearby instead of the one explicit base station for the given cell. This relaxing of the cell-boundaries massively improves performance and enables base-stations to forward data to each other to better serve users that would otherwise be difficult to reach. There are challenges with this approach however, including user scheduling and optimizing the location of base-stations, which still need to be researched [10].

Summary

This paper covers the preliminary research undergoing for 6G networks, the next generation of wireless networks to replace 5G. It analyzes the key motivating factors of next generation networks including advancements in blockchain technology, the need for higher data rates than existing networks such as 5G support, and advancements in AI/ML. The use cases of 6G are discussed including the emerging area of cyberspace and demand for improved vehicular networks. The technical requirements of 6G are covered, detailing the spectrum being considered for use and the physical infrastructure that will be required to support the THz band. The core architectural changes are discussed in contrast with the existing architecture of 5G networks and new physical layer techniques are described.

References

- H. Tataria, M. Shafi, A. F. Molisch, M. Dohler, H. Sjoland and F. Tufvesson, "6G Wireless Systems: Vision, Requirements, Challenges, Insights, and Opportunities," in Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 109, no. 7, pp. 1166-1199 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9390169)

- Z. Zhang et al., "6G Wireless Networks: Vision, Requirements, Architecture, and Key Technologies," in IEEE Vehicular Technology Magazine, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 28-41 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8766143)

- M. Alsabah et al., "6G Wireless Communications Networks: A Comprehensive Survey," in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 148191-148243 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9598915)

- L. U. Khan, I. Yaqoob, M. Imran, Z. Han and C. S. Hong, "6G Wireless Systems: A Vision, Architectural Elements, and Future Directions," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 147029-147044 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9163104)

- Choongil Yeh, Gweon Do Jo, Young-Jo Ko, Hyun Kyu Chung, Perspectives on 6G wireless communications, ICT Express, Volume 9, Issue 1 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S240595952100182X)

- Alsharif, Mohammed H., Anabi Hilary Kelechi, Mahmoud A. Albreem, Shehzad Ashraf Chaudhry, M. Sultan Zia, and Sunghwan Kim. "Sixth Generation (6G) Wireless Networks: Vision, Research Activities, Challenges and Potential Solutions" Symmetry 12, no. 4: 676 (https://www.mdpi.com/2073-8994/12/4/676)

- M. Z. Chowdhury, M. Shahjalal, S. Ahmed and Y. M. Jang, "6G Wireless Communication Systems: Applications, Requirements, Technologies, Challenges, and Research Directions," in IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society, vol. 1, pp. 957-975 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9144301)

- W. Saad, M. Bennis and M. Chen, "A Vision of 6G Wireless Systems: Applications, Trends, Technologies, and Open Research Problems," in IEEE Network, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 134-142 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8869705)

- P. Yang, Y. Xiao, M. Xiao and S. Li, "6G Wireless Communications: Vision and Potential Techniques," in IEEE Network, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 70-75 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8782879)

- I. F. Akyildiz, A. Kak and S. Nie, "6G and Beyond: The Future of Wireless Communications Systems," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 133995-134030 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9145564)

- Abdeljalil Beniiche, "6G and Next-Generation Internet," CRC Press, 2023, ISBN 9781000967210 (O'Reilly/Safari)

- Martin Maier, "6G and Onward to Next G," Wiley-IEEE Press, 2023, ISBN 9781119898542 (O'Reilly/Safari)

- Deepak Gupta, Mahmoud Ragab, Romany Fouad Mansour, Aditya Khamparia, Ashish Khanna, "AI-Enabled 6G Networks and Applications," Wiley, 2022, ISBN 9781119812647 (O'Reilly/Safari)

- Faisal Tariq, Khandaker Muhammad, Ansari Shafique Imran, "6G wireless: the communication paradigm beyond 2030," CRC Press, 2023, ISBN 9781003282211 (WUSTL)

- Yulei Wu, Sukhdeep Singh, Tarik Taleb, Adhishek Roy, Harpreet S Dhillon, Madhan Raj Kanagarathinam, Aloknath De, "6G Mobile Wireless Networks," Spring International, 2021, ISBN 9783030727772 (WUSTL)

Acronyms

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| 6DoF | 6 Degrees of Freedom |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BAN | Body Area Network |

| DSRC | Digital Short-Range Communication |

| IMT | International Mobile Telecommunications |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| MIMO | Multiple-Input Multiple-Output |

| NOMA | Non-Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| OFDM | Orthogonal Frequency Division Modulation |

| OFDMA | Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access |

| OFTS | Orthogonal Time-Frequency Space |

| OMA | Orthogonal Multiple Access |

| OSI | Open Systems Interconnect |

| PHY | OSI Physical Layer |

| RSU | Road-Side Unit |

| SI | Swarm Intelligence |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| U-MIMO | Ultramassive MIMO |

| V2I | Vehicle-to-Infrastructure |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |