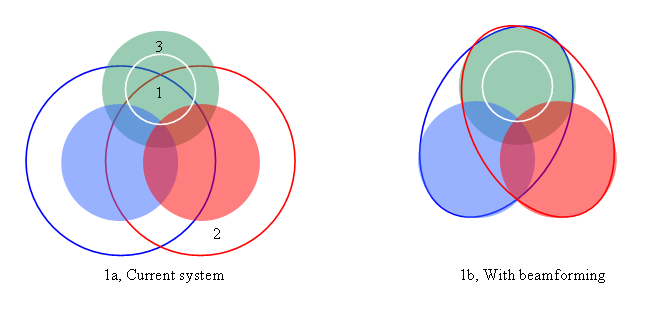

Figure 1: Smart Antennas

Section 2 discusses advanced modulation techniques. Section 3 describes different ways to use multiple antennas to achieve additional throughput or reduced bit-error rates. Section 4 describes options for more reliably encoding data. Section five discusses recent advances in radio architecture, specifically software-defined radios.

Modulation techniques concern the way spectrum is used to deliver a wireless signal from receiver to transmitter. Here, we discuss ultrawideband (UWB), Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing (OFDM), and the commercial status and implications of these technologies.

Ultrawideband (UWB) is a wireless transmission technology fundamentally different from other radio technologies. With UWB, data is represented by impulses, rather than carrier modulation. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), a prime financial supporter of UWB research, defines UWB as any wireless technology where the signal is 25% or more of the frequency used [McCorkle02]. UWB signals can spread over a spectrum range of up to 7 GHz, while carrier-based systems might have a 40 MHz or smaller bandwidth. Time-modulation pulse-position modulation and pulse polarity-modulation pulse-amplitude modulation are two modulation techniques used [WikipediaUWB]. UWB applications thus far have focused on extremely high-speed, shorter distance personal area networks (PANs). UWB is also called impulse, baseband, zero-carrier or modulated-wavelet technology.

UWB proponents note its potential for increased signal quality at reduced transmission power. The pulse duration of a UWB transmission, often as short as 1 ns, enables the transmitter to be on for a brief period of time, saving battery life in energy-constrained devices. Obstructions that prevent narrowband signals from reaching their intended targets are inconsequential to UWB, as its wideband nature ensures at least some part of the signal will pass through most obstacles. The extremely wide signal resists fading and jamming, while saving additional power through reduced retransmissions and higher coding density. UWB systems consume very little power, around one ten-thousandth of that of cell phones. [Geier03] The simple nature of pulse-based transmissions, combined with the falling costs of silicon, may lead to highly integrated UWB transceivers that are cheaper than equivalent carrier-based radios, due to the reduced need for complex analog modulation circuitry. These purported cost benefits have yet to be seen, primarily due to a lack of economies of scale.

Early UWB implementations encountered significant opposition from military and civil services who were worried about interference effects from UWB. Aviation, fire, police, and rescue services use radios in which the UWB signal overlaps their narrow spectrum. This overlap could create a safety conflict if the extra noise due to UWB were significant enough to those emergency service transmissions. The FCC evaluated the issue, decided it was not a threat, and passed a resolution in Feb 2002 enabling permission for low-power use of the 3.1 to 10.6 GHz spectrum area [Paulson03]. All UWB radios with FCC approval right now are considered to operate under the noise floor of carrier-based radios. In the near future, the FCC is expected to reevaluate their UWB findings for higher-power transmissions. The lack of FCC approval for high-power and long-range applications, as well as competing industry standards, may delay the technology's eventual application.

UWB has been primarily seen as a high-speed replacement for slow Bluetooth Personal Area Networks (PANs). An initial target is 480 Mbps, vs the 1-2 Mbps currently specified for Bluetooth devices. An IEEE task group, 802.15.3a, was created to standardize this application, but was dissolved in January 2006 after failing to unite the two largest industry players [Griffith06].

The physical layer portions of the standard operate between 3.1 and 10.6 GHz. WB-OFDM has been published by ECMA as a standard in ECMA-368 and ECMA-369, which are both ISO specs for the WiMedia UWB common radio platform. The goal of WiMedia is to enable interoperability with a range of upcoming networking standards, including Certified Wireless USB, Wireless 1394, Bluetooth SIG, and the old standard TCP/IP.

Within the WiMedia MAC specification is the MAC Convergence Architecture (WiMCA) that allows applications to share UWB resources and defines a number of policies. These policies include channel-time utilization, secure association, authentication and data transfer, device and WPAN management, quality of service, discovery of services, and power management. [WiMediaFAQ]

The WiMedia UWB common radio platform incorporates media access control (MAC) layer and physical (PHY) layer specifications based on multiband orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (MB-OFDM). WiMedia UWB is optimized for the PC, consumer electronics, mobile devices and automotive market segments. It requires a host wire adapter and a device wire adapter, and has been criticized as too PC-centric, as driver software is required.

As of April 2006, the commercialization status of UWB is unclear. A number of UWB products have been demonstrated at trade shows, but very few have reached the marketplace, in which consumer dollars will define the real UWB standard. The ubiquity of WiFi adoption may hinder UWB acceptance in marketplace. Belkin has released the CableFree USB Hub, based on the UWB Forum standard, and the WirelessUSB Hub supporting the WiMedia standard has been released [Griffith06a]. The data rate from both standards is sufficient for high-definition wireless video transmission, and if the FCC raises UWB power limits, there is a potential for wider Metropolitan Area Network (MAN) standardization and deployment.

The primary benefit to OFDM is spectrum efficiency; data rates can be increased by splitting a channel into smaller OFDM channels. Instead of increased data rate, the additional channels can be used to increase resistance to multipath interference, reduce timing sensitivity, or provide upstream/downstream speed flexibility. The technique enables easy implementation by Fast Fourier Transforms (FFTs) [WikipediaOFDM]

Use of OFDM is not without disadvantages, though. The tight channel spacing increases the receiver's sensitivity to frequency synchronization, which can result in poor performance. In addition, the technique results in a high peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR). The high PAPR requires expensive, highly linear electronics to handle the highly variable power requirements.

OFDM has been used in wired technologies for some time, including Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line (ADSL), and HomePlug powerline networking. Wireless applications are more recent, but have become commonplace in 802.11a and g Wireless LANs. OFDM is also used in 802.16 and the MB-OFDM UWB standard supported by the WiMedia group.

The primary disadvantage of smart antennas is the additional cost and complexity of the antenna element and signal processing electronics. However, one study estimates the additional station cost as ~30% additional. [Gesbert03]

Smart antennas enable performance gains in four areas: array gain, diversity gain, spatial multiplexing, and interference reduction. Array gain, also called beamforming gain, is an increase in the average SNR through a coherent combination effect of signals received at multiple antennas, or the gain of optimizing transmission in the direction of a user with a beamforming antenna. Array gain is proportional to the number of antennas [Paulraj05].

Diversity Gain comes from receiving multiple copies of a symbol through that fade independently. Random fluctuations in signal level are reduced, as it is highly probable that one copy of the received symbol will be received without interference. Space-time coding with MIMO is one form of diversity gain. Diversity gain is proportional to the product of the number of transmit and receive antennas [Alexiou04].

Spatial multiplexing gain comes from the transmission of independent data streams from multiple antennas. It enables a linear capacity increase with min(m,n), where m and n are the number of transmit and receive antennas, respectively.

Interference Reduction comes from precise control of transmitted and receive power or knowledge of properties of the received signal. It can mitigate the effects of co-channel interference from frequency reuse, using knowledge of the spatial signatures of the desired signal and co-channel signals

It is important to note that one can't get all these benefits (array gain, diversity gain, and spatial multiplexing) simultaneously! RF engineers seek a compromise that maximizes desired properties of the systems, like throughput, range, or reliability.

Multiple antennas help to reduce the effects of sources of noise, including scattering, reflection, refraction, fading, and thermal noise in the receiver. The greatest throughput gains come from diversity at both the transmitter and receiver.

Figure 1: Smart Antennas

The goal of MIMO is to maximize the data rate, and more specifically to improve the average capacity of a wireless link. In addition, maximum diversity is desired, as it minimizes the outage probability, or maximizes the outage capacity. MIMO optimally combines all copies of received signal to extract as much info as possible, and exploits multipath to do so. The technique enables a compromise between implementation complexity and performance.

Commercial MIMO faces some issues to implementation. For example, the gains in throughput are sensitive to channel conditions. Even worse, 1/2 lambda spacing is needed for uncorrelated fading. In laptops, this is not a limitation, but for handsets, 7.5 cm is often needed, which can be too small to fit multiple antennas. MIMO yields increased base station and receiver complexity; a (4,4) MIMO array yields approximately twice the complexity. System integration and signaling are also an issue, as radio resource control messages (RRC) required.

The upside for MIMO is that it works best for urban channels with uncorrelated fading. For this reason, as well as its potential for increased throughput, MIMO is included in the 3G (UMTS) cell phone standards, as well as the 802.11n and 802.16 wireless LAN standards.

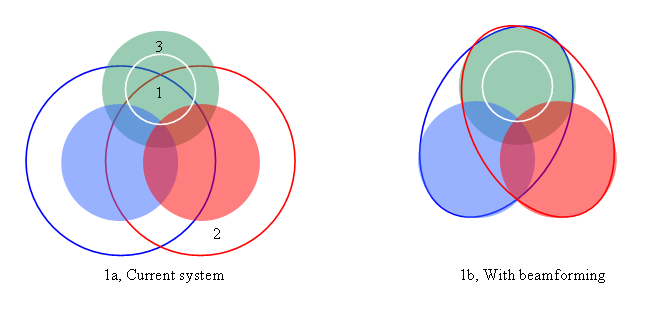

Figure 2: Space-Time Block Codes

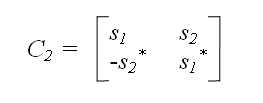

STBCs are defined by a number of parameters: transmit antennas, time slots, and symbols. Their properties include code rate, orthogonality, and diversity. The layout of an STBC matrix is show in Figure 2. Blocks are distributed among antennas and across time. Rows represent time slots, columns represent the signal at each transmit antenna, and length T is the number of blocks used to transmit the signal. Rate is equal to k/T, where k is the number of symbols.

Orthogonality is a term for the dependence between transmit antennas. In a fully orthogonal (FO) code, vectors representing any pair of columns are orthogonal. FO codes provide better error-rate performance in low SNR conditions and enable purely linear decoding. Quasi-orthogonal codes (QO) allow inter-symbol interference (ISI), but achieve full rate at the expense of more complex decoding. The QO Bit-error rate (BER) outperforms FO STBCs at low SNR, while under a high SNR, diversity from FO STBC's yields better BER than QO.

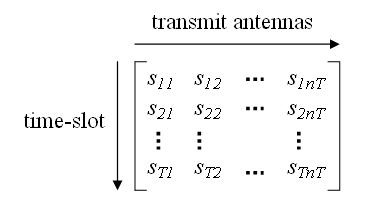

Figure 3: Alamouti's Code

The code rate is the number of symbols per time slot over one block. The optimal rate, full-rate, is also called Rate-1. The only known code to achieve this is Alamouti's Code for two antennas, shown in Figure 3. The * in the figure represents a complex conjugate. Alamouti's code is the only fully orthogonal Rate-1 code. Unfortunately, no code for greater than 2 transmit antennas can achieve rate-1. The maximum possible rate is 3/4 for greater than 3 antennas.

The evenness of signal power can be compromised with a non-orthogonal code; equal signal power is generally desired. High-rate codes often have long block length (decoding delay), as more blocks must be read before the symbols can be fully resolved.

Space-time block codes matter because they enable higher spectral efficiency (bps/Hz). They enable a compromise between rate maximization (BLAST) and diversity (space-time coding), and have a range of design options: orthogonality in the code, and the number of antennas to use. Feedback may help the error rates of these codes, but their commercialization status is unclear [Gesbert03].

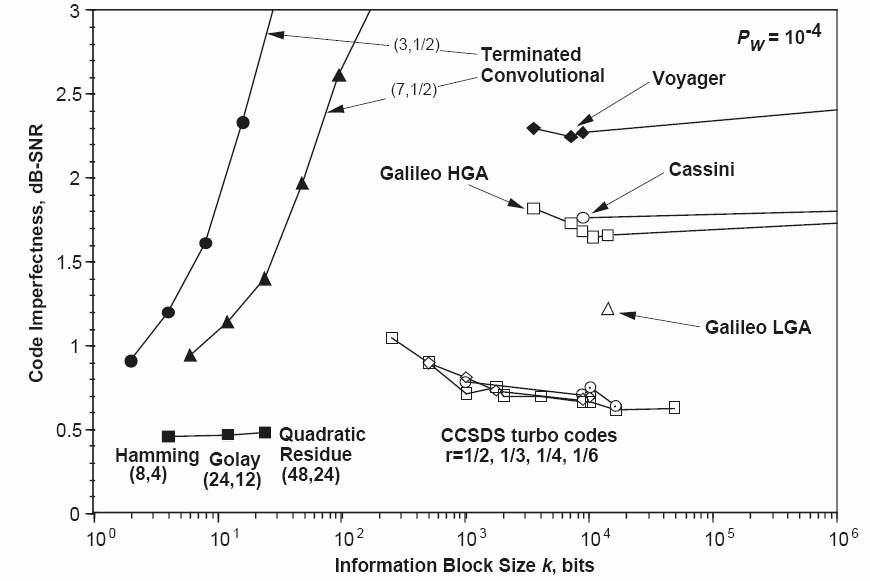

Figure X: NASA's Deep Space Missions ECC Codes

Figure 4: NASA's Deep Space Missions ECC Codes

Licensed under GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2

The primary advantage of Turbo Codes is their ability to increase the usable bit rate of a signal without increasing transmission power, or similarly, maintaining the bit rate of a signal while decreasing the transmission power. Few coding schemes have ventured closer to the Shannon limit of usable performance than Turbo Codes. The disadvantages are high decoding complexity and high decoding latency. These properties make TCs suboptimal for low-latency, battery-limited voice applications, but make them just fine for high-latency applications like NASA satellites and earth-orbit satellite TV systems, as shown in Figure 4. C = B * log2 (1 + P/N) Figure 5: Shannon capacity limit

Figure 5: Shannon capacity limit

The Shannon limit is the theoretical maximum information transfer rate of a channel, given a bandwidth and signal-to-noise ration of a channel [WikipediaTC]. The Shannon equation is show in Figure X. Shannon observed that the longer the codeword, the more difficult it was for noise to cause errors. By producing arbitrarily long codewords, one can approach the Shannon limit. Long codewords, however, have impractical space requirements, and the many bits transmitted per input bit reduce the useful transmit rate. Instead of producing a stream of bits from the signal, a turbo code receiver produces a likelihood measure for each bit. An iterative process of comparing parts of the codewords turns an impractical codeword space requirement into a tractable one that requires a number of steps. The two decoders converge on a solution, and report the result as a block of bits.

The transmit process requires a bit stream input, two identical encoders, and an interleaver. It produces a data stream and parity bits. Three copies of the input are generated. First, the parity is computed on the original input data. Second, the original data is transformed by the interleaver, and its parity computed. Third, the original data is appended. A word consisting of these three elements (parity of original data, parity of interleaved data, original data) is then sent.

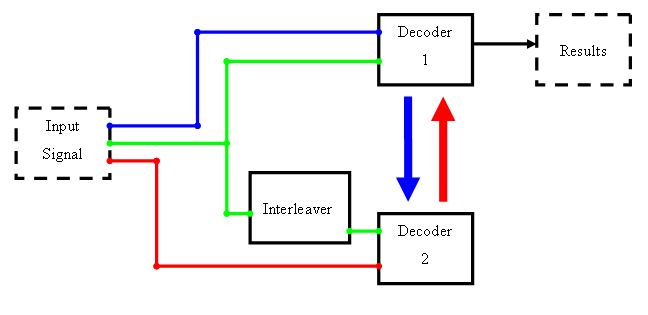

Figure 6: Receive Blocks

The receive process, shown in Figure 6, requires an analog input signal, two identical decoders, and an interleaver. It produces confidence value strings. The analog input signal is transformed into digital confidence values, as well as parity check values. Confidence values are exchanged between the decoders in an iterative data-exchange process. A strong 1 in one detector influences the other; both decoders continue to exchange data until their highest-likelihood solutions converge, which generally occurs in 4 to 10 steps.

Deep-space satellite communications were some of the first applications of Turbo Codes, as these signals experience high amounts of interference with atmospheric signals. The European Space Agency (ESA) SMART-1, Mars Reconaissance Orbiter (MRO), and Messenger satellites have all used TCs. The Universal Mobile Telecommunications Systems (UMTS) uses TCs when transmitting pictures, video, and mail. Note than voice is left off that list, because the large block size typically used with TCs presents excessive decoding delay. TCs are also used in satellite TV and Digital Audio Broadcasting.

The impact of Turbo Codes extends beyond just the high-performance codes themselves. Their unexpected creation showed information theorists that the creation of higher-performance error correction codes was indeed possible, and has inspired new coding techniques to deal with multipath propagation. In addition, they have inspired low-density parity check (LDPC) codes, which come even closer to the Shannon limit and are unencumbered by patents.

Software-Defined Radio (SDR) is orthogonal to the coding and transmission techniques discussed so far; it is a technique meant to enable fast, flexible switching between different frequency bands. Wide-bandwidth analog decoding electronics combine with sophisticated electronics to form a system that can emulate multiple radio protocols, enable concurrent listening to multiple frequencies, perform modulation and demodulation in software, and allow easy upgrades to new standards [Knight06].

SDR originate in the military, in the SpeakEasy project. Phase I worked between 2 MHz to 2 GHz, while SpeakEasy Phase II worked between 4 MHz and 400 MHz. SE Phase II was the first project to use FPGAs for radio processing. Its follow-on, the Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS), defined the Software Communications Architecture (SCA) that has found use in commercial applications [WikipediaSDR].

GNUradio is a free tool for amateur radio operators to use their computer's sound card analog input to listen to amateur radio stations. Research into RFID uses of SDR is ongoing, and supported by the SDR Forum [ SDR Forum].

[McCorkle02] McCorkle, J. "Why Such Uproar Over Ultrawideband?" CommsDesign Design Corner, Mar 1, 2002, http://www.commsdesign.com/design_corner/OEG20020301S0021

[UWBForum] UWB Forum, www.uwbforum.org.

[WiMedia] WiMedia Alliance, http://www.wimedia.org

[Paulson03] Paulson, L., "Will Ultrawideband Technology Connect in the Marketplace?," Computer, vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 15-17, Dec., 2003.

[Griffith06] Griffith, E., "802.15.3a is Dead: Long Live UWB", Ultrawidebandplanet.com, Jan 19, 2006, http://www.ultrawidebandplanet.com/resources/article.php/3578521.

[Griffith06a] Griffith, E., "First UWB/USB Products Announced", Ultrawidebandplanet.com, Jan 4, 2006, http://www.ultrawidebandplanet.com/products/article.php/3574771

[WiMediaFAQ] "WiMedia FAQs", WiMedia Alliance, http://www.wimedia.org/en/about/faq.asp?id=abt.

[WikipediaUWB] "Ultra wideband", Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultrawideband.

[Geier03] Geier, J., "A Technology to Consider: Ultrawideband", Feb 25, 2003, Wi-Fi Planet Tutorials, http://www.wi-fiplanet.com/tutorials/article.php/1598581

[Gifford06] Gifford, I., "DS-UWB enables convergence", Jun 14, 2004, Network World, http://www.networkworld.com/news/tech/2004/0614techupdate.html#graphic

[WikipediaOFDM] "Orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing", Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OFDM.

[Gesbert03] Gesbert, D. et al, "From Theory to Practice: An Overview of MIMO Space-Time Coded Wireless Systems", IEEE Journal On Selected Areas in Communications, Vol. 21, No. 3, April 2003.

[Paulraj05] Paulraj, A., "An Overview of MIMO Communications-A Key to Gigabit Wireless," Nov. 4, 2003, http://www.nari.ee.etHz.ch/commth/pubs/files/proc03.pdf

[Alexiou04] Alexiou, A. et al, "Smart Antenna Technologies for Future Wireless Systems: Trends and Challenges," Sept. 2004 Volume: 42, Issue: 9, pp 90- 97.

[Graham-Rowe04] Graham-Rowe, D., "Smart cellphone antennas boost coverage", Feb 1, 2004, NewScientist.com, http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn4613

[WikipediaSA] "Smart antenna", Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smart_antenna

[Tarokh98] Tarokh V. et al, "Space-Time Codes for High Data Rate Wireless Communication: Performance Criterion and Code Construction", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 1998

[Holden04] Holden, C., "Perfect Space-Time Block Codes", Dec. 14, 2004, http://www.math.wisc.edu/~boston/holden.pdf

[Teletar95] Teletar, E., "Capacity of multi-antenna gaussian channels", Oct. 1995, http://mars.bell-labs.com/papers/proof/proof.pdf

[Guizzo04] Guizzo, E., "Closing in on the perfect code", IEEE Spectrum, Mar. 2004, pp 36-42.

[WikipediaTC] "Turbo Code", Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turbo_code

[Berrou93] Berrou, C., "Near Shannon Limit Error-Correcting Coding and Decoding: Turbo Codes", IEEE 1993, 1070.

[WikipediaSDR] "Software Defined Radio", Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Software_defined_radio

[SDRForum] SDR Forum, http://www.sdrforum.org

[Knight06] Knight, W., "Software-defined radio could unify wireless world," NewScientist, Feb. 3, 2006.