Difference between revisions of "Python"

m (Changed the listed Python version.) |

m (Changed the listed Python version.) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

<source lang="bash">$ python --version</source> | <source lang="bash">$ python --version</source> | ||

| − | If it tells you a version of Python (like "3.6.1") then you're good to go. If not, you need to do a quick package install to get it up and running. Apt and Yum both call a functional Python package | + | If it tells you a version of Python (like "3.6.1") then you're good to go. If not, you need to do a quick package install to get it up and running. Apt and Yum both call a functional Python package <code>python3</code>. |

=== Pip === | === Pip === | ||

Revision as of 16:26, 30 March 2017

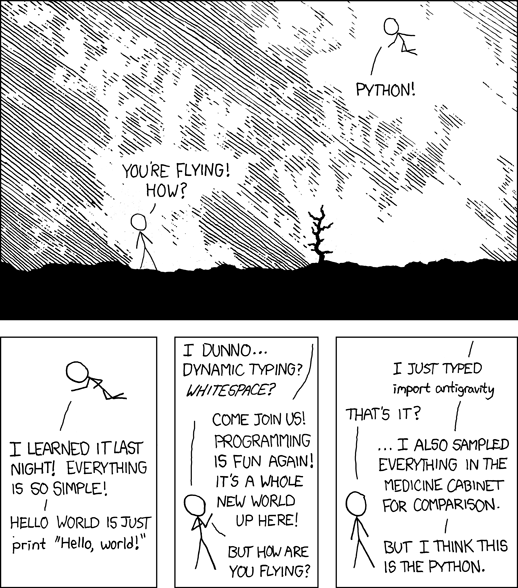

Languages like Java and C++ have lots of rules regarding variable types, syntax, return values, and so on. Although these restrictions help make the compiled program run quickly, they are cumbersome when you are trying to write short, quick scripts to perform tasks. This is where a scripting language comes into play.

Python is a language well-suited to rapid prototype development. It is an interpreted language, which means that you do not need to compile the code when you run it. The syntax is clean, and it is usually clear at first glance what is going on when you write in Python.

Installation

Python may already be installed on your system. To see whether or not it is, enter the command

$ python --version

If it tells you a version of Python (like "3.6.1") then you're good to go. If not, you need to do a quick package install to get it up and running. Apt and Yum both call a functional Python package python3.

Pip

Linux distributions have package managers like Apt, Yum, and YaST. PHP has a package manager named PEAR. It's now time to introduce Python's leading package manager: pip.

You need to install Pip from Apt or Yum before you can use it. Both call the package python-pip.

Once you have pip installed, you can use it to install Python packages. Use the pip-python (RHEL) or pip (Debian) command:

$ pip-python install package_name # RHEL

$ pip install package_name # Debian

Running Python

There are two common ways to run Python code: via the console, and via a Python script file.

The Python Console

The Python console enables you to experiment with code without opening a text editor. To enter the Python console, simply type the python command at the terminal:

$ python

To leave the interactive console, either type "quit()" or press Ctrl-D (on both Mac and Windows).

Python Script Files

You can also save Python script files for later use. The extension for Python scripts is *.py. To run a script file, simply feed its path as an argument to the python command in Terminal:

$ python my_script.py

Python Syntax and Language Components

This section contains a very brief overview of Python syntax. For a more comprehensive introduction, see the Python docs.

An Example Python Script

In my mind, there's no better way to learn Python than to be immersed in a simple example script.

print("Hello World")

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry", "date"]

for fruit in fruits:

print("I always love to eat a fresh %s." % fruit)

# Map the fruits list over to a new list containing the length of the fruit strings:

fruit_size = [len(fruit) for fruit in fruits]

avg_fruit_size = sum(fruit_size) / float(len(fruit_size))

print("The average fruit string length is %4.2f." % avg_fruit_size)

Some things to notice:

- Printing is achieved using the print function.

- A colon starts a block, similar to a curly brace { in many other languages. The corresponding code block must be indented. The end of the code block is signified by when the indentation ends.

- Strings can be printf-style formatted using the % operator

- Comments start with a pound symbol #

- We can transform/map a list to a new list in just one line. (Beat that, Java!)

- When we compute the average fruit size, we need to cast len(fruit_size), which returns an int, to a float in order to prevent integer truncation.

For some more examples, see the Python wiki.

Functions

Define functions using the def keyword:

def hello(name):

print("Hello, %s!" % name)

hello("Batman")

hello("Superman")

Lists

Unlike languages like Java and C, Python's array-like type doesn't have fixed length. Instead, a list is a dynamic array of objects of any type. Here's an example:

pets = ['Dog', 'Cat', 'Fish'] # Lists can be creating by placing their items between square brackets

random_items = ['Apple', 12312, 2.0, [1, 2, 3]] # Lists can contain objects of different types - even other lists!

pets.append('Turtle') # Adds 'Turtle' to the end of pets

Loops

Python while loops are written like this:

i = 0

while i < 10:

i += 1

Python for loops are written like this:

pets = ['Dog', 'Cat', 'Fish']

for pet in pets:

print(pet)

To iterate over a range of numbers, you can use the convenient range function, like so:

for i in range(20, 30): # Note, if you omit the first argument to range, it's assumed to be zero

print(i)

Unlike in other languages you may know, the following is not good practice in Python:

pets = ['Dog', 'Cat', 'Fish']

# BAD PRACTICE. DO NOT USE.

for i in range(len(pets)):

pet = pets[i]

Instead, if you need to access both a variable and its index, use the enumerate function, which allows you to iterate through a group of items, along with their indexes, like so:

pets = ['Dog', 'Cat', 'Fish']

for index, pet in enumerate(pets):

print("%s at index %d" % (pet, index))

Tuples

Python has a special datatype called tuple, which is an unmodifiable array.

cities = ('St. Louis', 'Los Angeles', 'Seattle') # Tuples are defined using parentheses.

single_item_tuple = (1,) # To make a tuple with only one item, put a comma after it

They can also serve as convenient ways to assign multiple variables at once:

first_name, last_name = "John", "Smith"

Tuples also enable you to have multiple return values from a function:

def compute_length(string):

str_len = len(string)

if str_len < 5:

return (str_len, "short")

elif str_len < 40:

return (str_len, "medium")

return (str_len, "long")

length, description = compute_length("Four score and seven years ago")

print("The %s string is %d characters long." % (description, length))

The above example also demonstrates Python's if...elif...else conditional structure.

Dictionaries

Python has another datatype called a dictionary (or dict, for short), which are like maps in Java, associative arrays in PHP, and object literals in JavaScript (coming up soon in Module 6). Essentially, they enable you to use any immutable object as the key in your data structure.

fruits_in_bowl = {

'apple': 4,

'banana': 2,

'cherry': 0,

'date': 12

}

apple_count = fruits_in_bowl['apple'] # Equals 4

fruits_in_bowl['pear'] = 9 # Sets 'pear' in the dictionary to 9.

for fruit, num in fruits_in_bowl.items():

print("There are %d %s(s) in the bowl." % (num, fruit))

If you only want the keys from a dictionary, you can just iterate over it directly, like this:

for fruit in fruits_in_bowl:

print(fruit)

If you want only the values but not the keys from a dictionary, use my_dictionary.values().

Generator Expressions and Comprehensions

A generator is a special kind of object that, basically, represents a collection of items using a value and a function for generating the next value in the collection. In other words, it's a way of creating something that behaves like a list, but which only generates one value at a time, and discards a value when it's done with it. Say, for example, you wanted to do an operation on 10,000,000,000,000 numbers. You could put them all in a list, then iterate over the list, but that would take a lot of memory, plus you'd have to create and fill the entire list before beginning to actually work on your problem. Instead, you'd probably be better off using a generator; telling the computer, essentially: "The starting value is 0. When I ask for the next number in the collection, add 1 to current value and give me that."

A generator expression is an expression that is evaluated to create a generator. They're super useful. Generator expressions can take two forms – they can be used with and without a condition:

(EXPRESSION for VARIABLE in ITERABLE) # Unconditional

(EXPRESSION for VARIABLE in ITERABLE if CONDITION) # Conditional

For our purposes, you can think of an iterable as anything you can do a for loop over. Let's take a look at a generator expression in use:

double_even_digits = (number * 2 for number in range(10) if number % 2 == 0)

That line says that double_even_digits is every even number between 0 and 10 multiplied by two. Simple enough, right? If we wanted to use all of the numbers, not just the even ones, we could simply remove the if statement at the end of the expression.

Here's the thing, though: if you were to print double_even_digits, instead of a nice bunch of numbers, you'd get something that looks like this:

<generator object <genexpr> at 0x107fc92b0>

That's because generators are lazy! They don't generate their values until those values are needed, and they discard values once they're no longer needed. As a result, you can only iterate over a generator once. In this case, you can't print out the whole generator, because it hasn't generated all the values yet. You can, however, iterate over the generator, and print its values one at a time, like so:

for number in double_even_digits:

print(number)

You can also make a list out of the generator, which will go through all the items in the generator and put them in a list, like so:

even_number_list = list(double_even_digits)

That's actually a great segue to the second topic of this section: comprehensions. A comprehension is just a prettier way to make lists, sets, and dicts out of a generator expressions.

# If you want a list:

list(i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0) # Don't do this

[i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0] # Use a list comprehension instead!

# If you want a set:

set(i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0) # Don't do this

{i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0} # Use a set comprehension instead!

# If you want a dict:

dict((i, i + 1) for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0) # Don't do this

{i : i + 1 for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0} # Use a dict comprehension instead!

# If you want a tuple:

tuple(i for i in range(10) if i % 2 == 0) # Unfortunately, there's no better way to do this

In general, generators and comprehensions should be used whenever possible - they're the fastest and easiest way to build collections. If you ever see yourself writing code like this:

# BAD PRACTICE! DO NOT USE!

digits = []

for digit in range(10):

digits.append(digit)

Don't do it! Instead, use a generator expression or comprehension as appropriate. A good way to decide whether a generator expression or comprehension is better for this situation is that, if you're just going to be iterating over your collection once, you should use an generator expression. If not, use a comprehension.

Sorting

Sorting in Python is frequently performed using the sorted function, which takes two arguments: an iterable (anything you can do a for-loop over, including lists and tuples) and a function used to evaluate each item. If the function is omitted, Python will try to sort the lists by value.

The following example demonstrates using an inline function, which Python calls a lambda.

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry', 'date']

# sort the fruits by string length

new_fruits = sorted(fruits, key=lambda v: len(v) // 2)

print(new_fruits) # ['date', 'apple', 'banana', 'cherry']

Alternatively, you can sort a list using the .sort method. This is faster than calling sorted, but it modifies the list in-place.

fruits = ['apple', 'banana', 'cherry', 'date']

fruits.sort()

Import

If you want to use functions from other libraries (including ones that you install using pip), use import:

import time

current_time = time.localtime()

print(time.strftime('%a, %d %b %Y %H:%M:%S', current_time))

If you want to pull the functions out of their namespace, you can use from ___ import ___ syntax:

from time import localtime, strftime

current_time = localtime()

print(strftime('%a, %d %b %Y %H:%M:%S', current_time))

# Be aware that this technique, although convenient, may cause unexpected behavior if the function names that you're pulling out of the namespace are already used for other purposes in Python.

File I/O

You can read an entire file into a variable like this:

f = open("example.txt")

file_contents = f.read()

f.close() # free up memory when we're finished with the file

A better option is to use a with-block, which handles opening and closing the file for you automatically:

with open("example.txt") as f:

file_contents = f.read()

You can read a file line-by-line like this:

with open("example.txt") as f:

for line in f:

print("Read line: %s" % line.rstrip())

You can write to a file like this:

with open("example.txt", "w") as f:

f.write("Hello\nWorld\n")

Command-Line Arguments

Command line arguments are accessible in the variable sys.argv.

The following example shows a program that expects a filename as its argument, and it prints a usage message if the argument is not present (source).

import sys, os

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

sys.exit("Usage: %s filename" % sys.argv[0])

filename = sys.argv[1]

if not os.path.exists(filename):

sys.exit("Error: File '%s' not found" % sys.argv[1])

Object-Oriented Programming

You can define and use a class like this:

class Food:

# constructor:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def format_name(self):

return "Gotta love to eat " + self.name

class Fruit(Food):

def format_name(self):

return Food.format_name(self) + " (fruit)"

fruit = Fruit("Cherry")

print(fruit.format_name())

print(Food.get_definition())

This is the same example as in the PHP guide.

Some things to notice:

- Instance methods always take self as their first argument, followed by any number of additional parameters. This can be misleading for programmers familiar with other languages, because the number of arguments you feed to the method is actually one less than the number of declared parameters. Whenever you call a method on a class instance, that instance is implicitly fed into the explicitly-declared self parameter of the method.

- Note that the self variable has the same purpose as the this variable in languages like PHP, Java, JavaScript, and C++.

- There is no need for a new keyword in Python.