Difference between revisions of "AJAX and JSON"

| (19 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

== The XMLHttpRequest Object == | == The XMLHttpRequest Object == | ||

| − | The JavaScript specification defines the '''XMLHttpRequest''' object, which is used to exchange data with the web servers without needing to reload the entire web page in the browser. | + | The JavaScript specification defines the '''XMLHttpRequest''' object (sometimes abbreviated as '''XHR'''), which is used to exchange data with the web servers without needing to reload the entire web page in the browser. |

| − | '''Note:''' | + | '''Note:''' For security reasons, you cannot perform AJAX requests to other domains, unless that domain has a special security policy set up to enable such requests. |

| − | + | === Javascript Fetch API === | |

| − | === | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | While creating an xhr object works, it's messy and hard to cleanly organize JavaScript's asynchronous nature. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Javascript has a [https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Fetch_API/Using_Fetch Fetch API] that you should be using. The Fetch API uses a concept in JavaScript known as a [https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Promise Promise] to represent the completion or failure of an asynchronous operation. | |

| + | An interesting discussion of XMLHttpRequest vs Fetch can be found [https://blog.openreplay.com/ajax-battle-xmlhttprequest-vs-the-fetch-api here]. | ||

=== Sending Data === | === Sending Data === | ||

==== GET Data ==== | ==== GET Data ==== | ||

| − | To send GET data, | + | To send GET data, create a fetch object with method "GET" |

<source lang="javascript"> | <source lang="javascript"> | ||

| − | + | fetch('/path/to/php/file', { | |

| − | + | method: "GET" | |

| − | + | }) | |

</source> | </source> | ||

| + | |||

| + | You can build your url to include GET variables if you want to send data. | ||

| + | ex: '/path/to/php/file?x='hi' | ||

==== POST Data ==== | ==== POST Data ==== | ||

| − | To send POST data, | + | To send POST data, create a fetch object with method "POST". You need to create an object of the data you want to send. |

<source lang="javascript"> | <source lang="javascript"> | ||

| − | + | const data = { x: 'hi', y: 'hello' }; | |

| − | + | fetch('/path/to/php/file', { | |

| − | + | method: "POST", | |

| − | + | body: JSON.stringify(data) | |

| + | }) | ||

</source> | </source> | ||

=== Listening for a Response === | === Listening for a Response === | ||

| − | + | When expecting a response from your php script, javascript's fetch api has a clean promise-based method of handling this. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

<source lang="javascript"> | <source lang="javascript"> | ||

| − | + | const pathToPhpFile = 'test.php'; | |

| − | + | const data = { x: 'hi', y: 'hello' }; | |

| − | + | fetch(pathToPhpFile, { | |

| − | + | method: "POST", | |

| + | body: JSON.stringify(data) | ||

| + | }) | ||

| + | .then(res => res.json()) | ||

| + | .then(response => console.log('Success:', JSON.stringify(response))) | ||

| + | .catch(error => console.error('Error:',error)) | ||

| + | </source> | ||

| − | + | You'll notice unfamiliar syntax here with the .then() methods attached. | |

| + | These are attaching event listeners to the end of your fetch request, and will trigger a function when your php script returns a response. | ||

| − | + | You should '''always''' have a catch block at the end, in case an error occurs in your response. In the near future, Javascript will ignore any requests that do not include a .catch() block. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==== Browser Support ==== | ==== Browser Support ==== | ||

Many examples that you find when Googling for "AJAX" use the '''onreadystatechange''' property of the XMLHttpRequest instance to react on the completion of the request, rather than using an event listener. This approach works, and it is required for comprehensive browser support, but it is no longer recommended for future use in modern web applications. The implementation of XMLHttpRequest documented here (so-called "XHR level 2") works in the following browsers: | Many examples that you find when Googling for "AJAX" use the '''onreadystatechange''' property of the XMLHttpRequest instance to react on the completion of the request, rather than using an event listener. This approach works, and it is required for comprehensive browser support, but it is no longer recommended for future use in modern web applications. The implementation of XMLHttpRequest documented here (so-called "XHR level 2") works in the following browsers: | ||

| − | * Firefox | + | * Firefox |

| − | * Safari | + | * Safari |

| − | * Chrome | + | * Chrome |

| − | * Opera | + | * Opera |

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Response Formats === | === Response Formats === | ||

| Line 101: | Line 86: | ||

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes" ?> | <?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes" ?> | ||

<note> | <note> | ||

| − | <date year=" | + | <date year="2023" month="02" day="14" /> |

<to>Sally</to> | <to>Sally</to> | ||

<message>Happy Valentine's Day!</message> | <message>Happy Valentine's Day!</message> | ||

| Line 120: | Line 105: | ||

</source> | </source> | ||

| − | == JSON == | + | ==== JSON ==== |

JavaScript Object Notation, or '''JSON''', is a rising standard interface format because of its lightweight syntax that makes it especially useful for AJAX requests. | JavaScript Object Notation, or '''JSON''', is a rising standard interface format because of its lightweight syntax that makes it especially useful for AJAX requests. | ||

| Line 172: | Line 157: | ||

Suppose you had the following PHP script: | Suppose you had the following PHP script: | ||

| + | Please note the difference in accessing POST data. | ||

<source lang="php"> | <source lang="php"> | ||

| Line 179: | Line 165: | ||

header("Content-Type: application/json"); // Since we are sending a JSON response here (not an HTML document), set the MIME Type to application/json | header("Content-Type: application/json"); // Since we are sending a JSON response here (not an HTML document), set the MIME Type to application/json | ||

| − | $username = $ | + | //Because you are posting the data via fetch(), php has to retrieve it elsewhere. |

| − | $password = $_POST['password'] | + | $json_str = file_get_contents('php://input'); |

| + | //This will store the data into an associative array | ||

| + | $json_obj = json_decode($json_str, true); | ||

| + | |||

| + | //Variables can be accessed as such: | ||

| + | $username = $json_obj['username']; | ||

| + | $password = $json_obj['password']; | ||

| + | //This is equivalent to what you previously did with $_POST['username'] and $_POST['password'] | ||

// Check to see if the username and password are valid. (You learned how to do this in Module 3.) | // Check to see if the username and password are valid. (You learned how to do this in Module 3.) | ||

| Line 187: | Line 180: | ||

session_start(); | session_start(); | ||

$_SESSION['username'] = $username; | $_SESSION['username'] = $username; | ||

| − | $_SESSION['token'] = | + | $_SESSION['token'] = bin2hex(openssl_random_pseudo_bytes(32)); |

echo json_encode(array( | echo json_encode(array( | ||

| Line 220: | Line 213: | ||

// ajax.js | // ajax.js | ||

| − | function loginAjax(event){ | + | function loginAjax(event) { |

| − | + | const username = document.getElementById("username").value; // Get the username from the form | |

| − | + | const password = document.getElementById("password").value; // Get the password from the form | |

| + | |||

| + | // Make a URL-encoded string for passing POST data: | ||

| + | const data = { 'username': username, 'password': password }; | ||

| − | + | fetch("login_ajax.php", { | |

| − | + | method: 'POST', | |

| − | + | body: JSON.stringify(data), | |

| − | + | headers: { 'content-type': 'application/json' } | |

| − | + | }) | |

| − | + | .then(response => response.json()) | |

| − | + | .then(data => console.log(data.success ? "You've been logged in!" : `You were not logged in ${data.message}`)) | |

| − | + | .catch(err => console.error(err)); | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

} | } | ||

| Line 253: | Line 242: | ||

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes" ?> | <?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes" ?> | ||

<note> | <note> | ||

| − | <date year=" | + | <date year="2023" month="02" day="14" /> |

<to>Sally</to> | <to>Sally</to> | ||

<message>Happy Valentine's Day!</message> | <message>Happy Valentine's Day!</message> | ||

| Line 319: | Line 308: | ||

<source lang="html4strict"> | <source lang="html4strict"> | ||

<div id="note"> | <div id="note"> | ||

| − | <strong> | + | <strong>2023-02-14</strong> |

<p>Dear Sally,<br /><br />Happy Valentine's Day!<br /><br />Love, Your Secret Admirer</p> | <p>Dear Sally,<br /><br />Happy Valentine's Day!<br /><br />Love, Your Secret Admirer</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</source> | </source> | ||

| − | + | == Debugging AJAX and JSON == | |

| + | |||

| + | It is helpful when building your application to look at the AJAX requests and responses as they happen in real time. Fortunately, there are many tools to help. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In your favorite web inspector (Chrome Dev Tools, Mozilla Dev Tools, Firebug, Dragonfly, and so on), go to the "Network" tab. This is where you can see all assets loaded by the application: images, stylesheets, and, most importantly for us, AJAX files. Some inspectors let you filter requests by type; for example, the Chrome inspector lets you click "XHR" to only show XMLHttpRequest (AJAX) requests. | ||

| + | |||

| + | You can also view the JSON sent by your server. Double-clicking the entries in the web inspector opens the source URL in a new tab. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you find minified JSON hard to read, we recommend that you install the JSONView browser extension or one of its close relatives: | ||

| + | * [https://addons.mozilla.org/en-us/firefox/addon/jsonview/ Firefox] | ||

| + | * [https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/jsonview/chklaanhfefbnpoihckbnefhakgolnmc?hl=en Chrome] | ||

| + | * [https://addons.opera.com/en/extensions/details/jsonviewer/ Opera] | ||

| + | * [https://github.com/rfletcher/safari-json-formatter Safari] | ||

[[Category:Module 6]] | [[Category:Module 6]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:55, 9 June 2023

Asynchronous Javascript And XML, or AJAX, is a group of related web development techniques, standards, and technologies used on the client (web browser) side of the standard web server-client communication model.

Here's the general concept: JavaScript is used to send requests to the web server in the background and retrieve data, without the need to refresh the page. The result: dynamic, fast, user-friendly web pages.

The requests are performed asynchronously: this means that the end user can continue interacting with your web page while the server data is being loaded.

The key idea is that a large fraction of the work happens at the web browser, and larger requests happen behind the scenes, keeping waiting times for data to come back over the network to a minimum. AJAX is generally also associated with higher-level APIs and libraries that aid in producing cleaner user interfaces for web applications.

The XMLHttpRequest Object

The JavaScript specification defines the XMLHttpRequest object (sometimes abbreviated as XHR), which is used to exchange data with the web servers without needing to reload the entire web page in the browser.

Note: For security reasons, you cannot perform AJAX requests to other domains, unless that domain has a special security policy set up to enable such requests.

Javascript Fetch API

While creating an xhr object works, it's messy and hard to cleanly organize JavaScript's asynchronous nature.

Javascript has a Fetch API that you should be using. The Fetch API uses a concept in JavaScript known as a Promise to represent the completion or failure of an asynchronous operation.

An interesting discussion of XMLHttpRequest vs Fetch can be found here.

Sending Data

GET Data

To send GET data, create a fetch object with method "GET"

fetch('/path/to/php/file', {

method: "GET"

})

You can build your url to include GET variables if you want to send data. ex: '/path/to/php/file?x='hi'

POST Data

To send POST data, create a fetch object with method "POST". You need to create an object of the data you want to send.

const data = { x: 'hi', y: 'hello' };

fetch('/path/to/php/file', {

method: "POST",

body: JSON.stringify(data)

})

Listening for a Response

When expecting a response from your php script, javascript's fetch api has a clean promise-based method of handling this.

const pathToPhpFile = 'test.php';

const data = { x: 'hi', y: 'hello' };

fetch(pathToPhpFile, {

method: "POST",

body: JSON.stringify(data)

})

.then(res => res.json())

.then(response => console.log('Success:', JSON.stringify(response)))

.catch(error => console.error('Error:',error))

You'll notice unfamiliar syntax here with the .then() methods attached. These are attaching event listeners to the end of your fetch request, and will trigger a function when your php script returns a response.

You should always have a catch block at the end, in case an error occurs in your response. In the near future, Javascript will ignore any requests that do not include a .catch() block.

Browser Support

Many examples that you find when Googling for "AJAX" use the onreadystatechange property of the XMLHttpRequest instance to react on the completion of the request, rather than using an event listener. This approach works, and it is required for comprehensive browser support, but it is no longer recommended for future use in modern web applications. The implementation of XMLHttpRequest documented here (so-called "XHR level 2") works in the following browsers:

- Firefox

- Safari

- Chrome

- Opera

Response Formats

More often than not, a plaintext response form the server is not very helpful: you want to transmit more information than simply a single string of text. There are two good options to get more information from a single AJAX request: XML (the original format, thus the X in AJAX) and JSON.

XML

Your server can respond with an XML document (whence, XMLHttpRequest). An XML document uses syntax that is extremely close to HTML For example:

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes" ?>

<note>

<date year="2023" month="02" day="14" />

<to>Sally</to>

<message>Happy Valentine's Day!</message>

<from>Your Secret Admirer</from>

</note>

Like HTML, XML has a DOM that can be traversed in JavaScript.

If you make an AJAX request to a script generating an XML document, the root XML node is accessible in the responseXML property.

function ajaxCallback(event){

var xmlDocument = event.target.responseXML;

alert(xmlDocument.getElementsByTagName("to")[0].textContent); // Sally (in the case of the example XML above)

}

JSON

JavaScript Object Notation, or JSON, is a rising standard interface format because of its lightweight syntax that makes it especially useful for AJAX requests.

The JSON syntax closely follows the syntax for object literals. For example:

{

"apple": {

"color": "red",

"flavor": "sweet"

},

"lemon": {

"color": "yellow",

"flavor": "sour"

}

}

Usually when JSON is transferred over the internet, it is condensed down to one line, like this:

{"apple":{"color":"red","flavor":"sweet"},"lemon":{"color":"yellow","flavor":"sour"}}

In JavaScript, you can convert a JSON string to an object using JSON.parse(). For example:

var jsonData = JSON.parse('{"apple":{"color":"red","flavor":"sweet"},"lemon":{"color":"yellow","flavor":"sour"}}');

alert(jsonData.apple.color); // red

Here's how to use it in conjunction with your AJAX response callback:

function ajaxCallback(event){

var jsonData = JSON.parse(event.target.responseText);

alert(jsonData.lemon.flavor); // sour (in the case of the example JSON above)

}

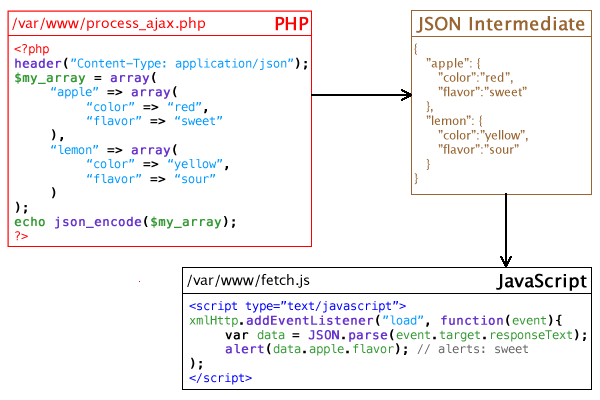

Here is a graphic to illustrate the JSON process.

Examples

Logging In a User

Suppose you had the following PHP script: Please note the difference in accessing POST data.

<?php

// login_ajax.php

header("Content-Type: application/json"); // Since we are sending a JSON response here (not an HTML document), set the MIME Type to application/json

//Because you are posting the data via fetch(), php has to retrieve it elsewhere.

$json_str = file_get_contents('php://input');

//This will store the data into an associative array

$json_obj = json_decode($json_str, true);

//Variables can be accessed as such:

$username = $json_obj['username'];

$password = $json_obj['password'];

//This is equivalent to what you previously did with $_POST['username'] and $_POST['password']

// Check to see if the username and password are valid. (You learned how to do this in Module 3.)

if( /* valid username and password */ ){

session_start();

$_SESSION['username'] = $username;

$_SESSION['token'] = bin2hex(openssl_random_pseudo_bytes(32));

echo json_encode(array(

"success" => true

));

exit;

}else{

echo json_encode(array(

"success" => false,

"message" => "Incorrect Username or Password"

));

exit;

}

?>

Note: This example uses PHP's very handy json_encode() function to translate an associative array into a JSON object. This means that you can access in JavaScript the same structure that you made in PHP!

And suppose you had the following HTML content:

<input type="text" id="username" placeholder="Username" />

<input type="password" id="password" placeholder="Password" />

<button id="login_btn">Log In</button>

<script type="text/javascript" src="ajax.js"></script> <!-- load the JavaScript file -->

You could use the following JavaScript code to prepare, send, and receive a request from the server to see if the user is logged in, without ever having to refresh the page.

// ajax.js

function loginAjax(event) {

const username = document.getElementById("username").value; // Get the username from the form

const password = document.getElementById("password").value; // Get the password from the form

// Make a URL-encoded string for passing POST data:

const data = { 'username': username, 'password': password };

fetch("login_ajax.php", {

method: 'POST',

body: JSON.stringify(data),

headers: { 'content-type': 'application/json' }

})

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => console.log(data.success ? "You've been logged in!" : `You were not logged in ${data.message}`))

.catch(err => console.error(err));

}

document.getElementById("login_btn").addEventListener("click", loginAjax, false); // Bind the AJAX call to button click

Note: The above example uses an anonymous function (a function without a name that is declared in an attribute) as the callback. If you are using a certain callback function only once in your program, this is a perfectly valid approach to reduce the amount of code you need to write.

Loading Data from an XML File for Display in HTML

Suppose you have a file note.xml that contains the following information:

<?xml version="1.0" standalone="yes" ?>

<note>

<date year="2023" month="02" day="14" />

<to>Sally</to>

<message>Happy Valentine's Day!</message>

<from>Your Secret Admirer</from>

</note>

Further, suppose you had an HTML element with ID note:

<div id="note"></div>

You could load this XML file and then display it inside of your HTML document like this:

function getNoteAjax(event){

// The XMLHttpRequest is simple this time:

var xmlHttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

xmlHttp.open("GET", "note.xml", true);

xmlHttp.addEventListener("load", getNoteCallback, false);

xmlHttp.send(null);

}

function getNoteCallback(event){

var htmlParent = document.getElementById("note"); // Get the HTML element into which we want to write the note

var xmlDocument = event.target.responseXML; // Get the XML root node from the response

// Find the <date/> element from the XML response. We expect only 1 such element, so we can call

// xmlDocument.getElementsByTagName() and then get the first (and only) element in the array all in

// one step. This is called chaining.

var xmlDateElement = xmlDocument.getElementsByTagName("date")[0];

// Put together a YYYY-MM-DD type date into a string based on the attributes of the <date/> element.

var dateString = xmlDateElement.getAttribute("year") + "-" + xmlDateElement.getAttribute("month")

+ "-" + xmlDateElement.getAttribute("day");

// Get the content of the <to>, <message>, and <from> tags. Again, you can use a chain to do this in one line for each.

var to = xmlDocument.getElementsByTagName("to")[0].textContent;

var message = xmlDocument.getElementsByTagName("message")[0].textContent;

var from = xmlDocument.getElementsByTagName("from")[0].textContent;

// Make a <strong> tag, append the date string as its content, and then append it to the HTML element.

var htmlDateObj = document.createElement("strong");

htmlDateObj.appendChild(document.createTextNode(dateString));

htmlParent.appendChild(htmlDateObj);

// Make a <p> tag to contain the note.

var htmlParagraphObj = document.createElement("p");

htmlParagraphObj.appendChild(document.createTextNode("Dear "+to+",")); // First append the greeting

htmlParagraphObj.appendChild(document.createElement("br")); // Append a couple line feeds

htmlParagraphObj.appendChild(document.createElement("br"));

htmlParagraphObj.appendChild(document.createTextNode(message)); // Write the message itself

htmlParagraphObj.appendChild(document.createElement("br")); // Append a couple more line feeds

htmlParagraphObj.appendChild(document.createElement("br"));

htmlParagraphObj.appendChild(document.createTextNode("Love, "+from)); // Finally, append the salutation

htmlParent.appendChild(htmlParagraphObj); // Append the newly engineered <p> to the HTML element.

}

document.addEventListener("DOMContentLoaded", getNoteAjax, false); // Bind the AJAX call to page load

This example uses a lot of techniques documented in the JavaScript#Document Object Model section above. The resulting DOM will be something like this:

<div id="note">

<strong>2023-02-14</strong>

<p>Dear Sally,<br /><br />Happy Valentine's Day!<br /><br />Love, Your Secret Admirer</p>

</div>

Debugging AJAX and JSON

It is helpful when building your application to look at the AJAX requests and responses as they happen in real time. Fortunately, there are many tools to help.

In your favorite web inspector (Chrome Dev Tools, Mozilla Dev Tools, Firebug, Dragonfly, and so on), go to the "Network" tab. This is where you can see all assets loaded by the application: images, stylesheets, and, most importantly for us, AJAX files. Some inspectors let you filter requests by type; for example, the Chrome inspector lets you click "XHR" to only show XMLHttpRequest (AJAX) requests.

You can also view the JSON sent by your server. Double-clicking the entries in the web inspector opens the source URL in a new tab.

If you find minified JSON hard to read, we recommend that you install the JSONView browser extension or one of its close relatives: