This document provides assorted links and advice to help you use a word processor or editor to write your assignments. My goal is not to provide complete documentation but rather to give you pointers on how to get started and what kind of functionality you should look for in tools to compose CSE assignments. I assume that you are already familiar with basic word processing or text editing, so I'll focus on two areas of particular importance: writing math and drawing figures.

For a summary of formatting requirements specific to this class, as well as submission procedures, please see the accompanying eHomework guide.

I will discuss features of four different tools: LaTeX, Microsoft Word, LibreOffice, and Google Docs.

LaTeX is free for Windows, Mac, and Linux (among other operating systems!). For information on where to get it for your machine, see these recommendations. For Windows users, the recommended Windows package includes the TeXstudio interactive LaTeX editor. For Mac users, you can install the TeXShop tool to view your LaTeX documents in formatted form. You can also begin to use LaTeX immediately, without installing anything, by using Overleaf, a web-based LaTeX editor that interactively previews your formatted document as you type.

If you are a current Wash U. student, you can obtain Microsoft Word for free (for Windows or Mac) as part of the university's Office 365 program. Note that the above link gets you the full, locally installed Office suite of applications; the web-based Office Online apps lack the capability to compose math formulas. If you already have Office 2007+ for Windows or 2011+ for Mac, you don't need to upgrade to use the features described below.

Google Docs runs in your web browser; there's nothing to install, though you will need a Google account.

LibreOffice is freely available from The Document Foundation. You can get either for Windows, Mac, or Linux.

Unlike the other tools listed above, LaTeX is not an interactive word-processor. You use a plain text editor to prepare your source document, then use LaTeX to build the PDF from this source. Within the source document, you specify mathematical formulas using markup, but you won't see the typeset results until you build the PDF (though some tools, like Overleaf, continually rebuild a preview for you in the background as you type).

LaTeX is the preferred tool of computer scientists and mathematicians everywhere for writing research papers and documentation. I've used LaTeX for over 20 years; it's what I use to typeset assignments and handouts. Even if you do all your composing for the web, you can use LaTeX math to build equations on your pages using MathJax. Please give serious consideration to learning LaTeX -- it is incredibly flexible and powerful, whether you're writing a homework, a paper, or an entire book. Take a look at this example code to get started, and see below for pointers to much documentation.

A huge variety of tools is available to add mathematical formulas and symbols to your documents. All require investing some time to learn, so you should consider which tools will let you do what you need efficiently, now and in the future.

Some key questions to ask about any math composition tool are:

If you compose documents containing math, you will soon realize the benefits of being able to enter formulas and symbols directly from the keyboard, without breaking the flow of composition. Moreover, if you expect your documents to be printed at high resolution, viewed at multiple sizes, or translated into different file formats (PDF, HTML, etc.), it is essential that your equations be represented symbolically rather than as images. I would not invest time learning a tool that does not offer both keyboard composition of formulas and symbolic representation of the results.

It used to be that if you wanted keyboard math entry in your editor, you either used LaTeX or bought a commercial add-on for Word, such as MathType. These may still be the best choices if you are publishing research papers in math or theoretical CS. However, for purposes of homework, you can get by just fine with other tools' built-in math support.

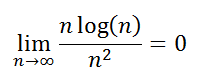

To enter math from the keyboard, you use a markup language that lets you name special symbols and operators with multi-character strings. Each tool has its own markup language, though they all share some similarities. For example, suppose I want to enter the formula

In LaTeX, I would type

\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty} \frac{n \log(n)}{n^2} = 0

The same formula in MS Word's native markup would be entered as

lim_(n\to\infty) n log(n)/n^2 = 0while in LibreOffice, I would enter

lim csub {n rightarrow infty} {{n log(n)} over {n^2}} = 0

In Google Docs, the formula would be entered (including spaces and newlines) as

\lim n\rightarrow\infty \frac n \log(n) n^2 = 0You'll have to learn the markup language used by your software of choice.

Math markup in LaTeX is typed in plain text, just like the rest of your document. You can include math markup in the middle of a line of text by enclosing it in "$" characters before and after. If you want a displayed equation set on its own line, you instead enclose the markup with the pair "\[" and "\]". Fancier enclosing directives are available if you want numbered formulas or a horizontally aligned stack of formulas.

To get started writing LaTeX documents, take a look at this online tutorial and/or this introduction. Lesson 4 of the tutorial or Sections 3.2-3.3 of the introduction provide all the information you need to write simple formulas, though Sections 3.5 and following of the latter offer more advanced constructs that you may find useful. You can also consult this more detailed reference manual (chapter 16 is about math mode) or this Wiki-based book on LaTeX. Or, if you just want an example to get started, here's an example.

We provide a LaTeX template for your assignment as part of the eHomework guide.

If you want to practice your LaTeX math markup, try this web service, which interactively typesets LaTeX math into a (bitmapped) image as you type. You can also enter LaTeX math markup directly in Piazza comments by enclosing it in the pair of characters "$$" both before and after.

Word versions 2007 or newer for Windows and 2011 or newer for Mac have good support for composing mathematical formulas. Unfortunately, math support has not been ported to Word Online (as of August 2018).

Microsoft provides decent documentation on how to compose mathematical formulas from the keyboard in Word. In mid-2017, Office 365 (but not the standalone, perpetually licensed Office 2016) acquired the ability to enter LaTeX math markup from the keyboard, at least in Word. Unless you already know how to typeset formulas using Microsoft's markup, or you really want to get into the grody details, I would suggest using LaTeX markup. You can also use LaTeX math in PowerPoint, but doing so right now requires configuring some magic macros first. There are a few (relatively obscure) LaTeX math features that are not supported or supported differently by Office; see the above documentation from MS for details.

If you choose/need to use Office's math markup language, you may find this cheat sheet useful. For Mac users of Office 2011, you may want to read this summary of how the Mac and Windows versions of math support differ.

I find that the automatic conversion of markup to math as you type (which Word calls "math autocorrect") can sometimes behave unpredictably -- especially with fractions, where Word has difficulty telling where the denominator ends. This is true whether you use MS or LaTex markup in Word. You may have the best experience with a mix of markup and toolbar-based usage. Note that you can go back and edit a formula interactively using the menu ribbon once you've typed it in, so it's OK if your first cut at entering a formula isn't perfect.

Finally, if you want to have convenient access to math symbols such as Greek letters and operators while writing plain text (not just in displayed equations), the following recipe works in Word 2010 for Windows, and there should be very similar tricks in other versions. Go to File/Options/Proofing, select "AutoCorrect Options", choose the "Math AutoCorrect" tab, and check "Use Math AutoCorrect outside of math regions". You will now be able to enter markup for special characters, such as \alpha or \leq, while typing ordinary text and have them converted to symbols on the fly.

To learn how to typeset math in LibreOffice, read their Math Guide.

LibreOffice acts a bit differently than Word or Google Docs, in that you have to enter math markup in a window separate from the main document. You can use the three-key sequence "Alt-i o f" to start entering a formula and Esc to finish without leaving the keyboard. I've found LibreOffice more predictable in interpreting markup than Word or Google Docs because you can easily enclose things like the subscript of a limit or the numerator and denominator of fractions in curly braces, which removes any ambiguity about your intent.

If you want to enter LaTeX math in LibreOffice, you'll need both the TexMaths extension and a full LaTeX installation on your machine. The resulting equations will be either bitmaps (undesirable!) or SVG vector graphics (better). I have not tried this myself.

First, if you're using Google Docs primarily because you like the convenience of a web-based tool with cloud storage and collaborative editing for your documents, consider writing LaTeX instead using Overleaf, which offers all of those things.

You should start by reading the documentation for Google Docs' math mode. Note that from the keyboard (in Windows), you can type the two-key sequence "Alt-shift-i e" to begin entering an equation without using the menu ribbon; something similar undoubtedly works on the Mac.

Google Docs' repertoire of math symbols is somewhat limited, as it lacks support for linear algebra and arrays of equations. I have also found the behavior of keyboard formula entry to be a bit quirky, for reasons similar to MS Word.

There is an external add-on called "Auto-LaTeX Equations" available for Google Docs that lets you enter LaTeX markup and formats the result using a 3rd-party service. Unfortunately, the results are rendered as images rather than in symbolic form.

NB: if you go looking for additional online help with Google Docs' math mode, you should know that around 2011, Google switched to the current interface from an older one based on LaTeX. Advice from before 2012 is likely to be outdated. Also, somewhere around 2016, many older add-ons that supported LaTeX math entry broke when Google changed the Docs add-on API.

You can draw and save figures either as bitmapped images or as vector graphics, which are encoded as a series of curves and lines. Vector graphics are preferable, since they look good in print and on any size screen. Ideally, your editor should have robust support for composing figures using vector graphics natively and/or importing them into your document in a standard vector format such as PDF or EPS.

Of the programs discussed here, LaTeX has the strongest support for importing PDFs and other vector images but requires using a 3rd-party tool to draw them. The other three programs each offer a native composition tool for figures and can either include natively composed figures in their own document type or export them as PDFs. However, while these programs can import bitmapped images in a variety of formats, they all have limited or broken support for importing PDF (or other vector) figures. Hence, if you want vector graphics in your document, it's best to use the program's drawing tool to compose it natively. Otherwise, you may have to convert your figure to a bitmapped image, with the attendant loss of quality, to get it into your document.

LaTeX, not being a WYSIWYG word processor, does not support interactive figure drawing. However, it has excellent support for importing figures and images from other programs.

\includegraphics[width=xx]{foo}

where "xx" is the desired width of your figure in the document. I

recommend replacing xx by "y \textwidth", where where "y" is a

floating-point number between 0 and 1. This makes your figure a y

fraction of the width of a text line on the page and keeps its height

proportional to its width.

LaTeX does have a facility for specifying vector graphics directly using markup. However, rather than use this raw facility, you should instead consider more powerful graphics markup languages such as TikZ. If you want to draw figures of finite automata, check out the VauCanSon-G add-on package.

Word supports insertion of shapes and lines directly into a document. For figures containing more than one shape, you should first create a new drawing canvas (see the option at the bottom of Insert/Shapes), then draw your figure inside the canvas. You can also create a figure on a blank page in PowerPoint and cut and paste that figure into your document.

An annoying property of Word figures is that resizing them rarely works as expected. Changing the size of a canvas does not scale the contents by default, though this can be changed on a per-canvas basis. You can grab all the objects in the canvas and resize them together. Unfortunately, resizing does not change the font size of any text in your figure, which often leads to bizarre results!

To resize a figure in a canvas or from PowerPoint uniformly, copy it to the clipboard and then paste it as an image into your document. The result will still be stored as vector graphics, but it will resize as a unit. However, you will not be able to edit the resulting figure. For this reason, it is wise to create and store editable versions of your figures in a separate document (Word or PowerPoint) and then paste them as images into your assignment as needed.

PDFs can be imported into Word documents as external objects. On a Mac, the figure is displayed using the OS's native support for PDF and may enable you to produce high-quality PDF versions of your document with all figures. On Windows, however, Word requires an external program such as Adobe Acrobat to render the figure. It will look great inside Word, but when you save your document as a PDF, you will get a low-resolution bitmap in place of the vector graphic.

You can use the LibreOffice Draw tool to create figures, which can be saved as PDF or in the tool's native .odg format. To get a figure produced with Draw into your document, you can copy it to the clipboard and paste it into Writer. You can also create figures directly in Writer using its "Drawing" toolbar. To keep your figure together, you may wish to insert a frame first and draw inside that.

To resize a figure drawn within Writer or Draw, you'll have to resize the component objects. Unfortunately, resizing a figure does not resize the text (similar to MS Word). To work around this limitation, you can select your entire figure in Draw and perform "Modify/Convert to Curve", which turns all the text into shapes that resize along with the rest of the figure. However, once you do this, you can no longer edit the figure's text -- so make a backup of your figure first!

As of LibreOffice 6.1, importing a PDF figure directly into a document in Write using 'Insert/Image' appears to work -- the figure displays as a bitmap inside Write but is saved in its vector form. Unfortunately, LibreOffice's PDF exporter does not respect the figure's PDF bounding box, so exporting the final document as a PDF may produce incorrect results. (This is a long-standing bug in LibreOffice's PDF exporter.) You can instead convert PDF figures to .odg format by opening them in Draw, then proceed as above. Note that the conversion may not preserve all the characteristics of your original figure (especially fonts), so check carefully after importing.

Use the "Drawing" tool in Google Docs to create figures, which are then embedded in your document. Unlike in Word or LibreOffice, resizing a figure resizes its text as expected. You can also download your figure as a PDF that can be added to documents in other programs.

There does not appear to be a way to insert an external PDF figure into your document as a vector graphic. There are many (largely obsolete or unsatisfactory) workarounds described on the web -- caveat emptor.

As we've seen, PowerPoint, LibreOffice Draw, and Google Drawing are three tools that can produce PDF figures for use in your documents. Many other figure drawing tools exist. In particular, you may want to look at InkScape, a very feature-rich drawing tool similar to Adobe Illustrator. For drawing trees and graphs, I've heard good things about yEd, which now has a web-based "live" version as well.

If you produce PDFs for your figures, you will often find that you need to crop them to remove surrounding white space when inserting them into your document. If your drawing tool of choice (I'm looking at you, PowerPoint) doesn't support cropping or saving with a tight bounding box, you will need some other way to do this. Most editors let you crop a figure after insertion (LaTeX does so via the "bb" option to \includegraphics), but this doesn't help much if you can't see the figure in order to crop it!

Mac users can use the built-in Preview tool to crop PDFs. For Windows, a popular free tool is Briss. If you are comfortable working from the command line (particularly Linux users, who may already have all the needed tools installed), check out pdfcrop. Finally, most commercial PDF editors, such as Adobe Acrobat, Foxit, PDF-XChange, or Nitro Pro, support cropping and otherwise editing PDFs.